Why care about zoning?

Land use restrictions haven't just made housing more expensive. They're making everything else worse too.

Stringent land use regulations have made housing more expensive, as talked about previously here, and the problem will continue to get worse until permanent solutions are implemented. But housing being more expensive is just the tip of the iceberg: insufficient houses also mean lower growth, more carbon emissions, more inequality, and less effective monetary policy - all of which have far-reaching implications.

The NIMBYs make the pie smaller

Cities across the US have different levels of productivity, especially of labor. The labor market is very complicated but, in general, we can say that higher productivity tends to mean higher wages. If a factory worker in Dallas can make twice as many products per hour than a factory worker in Cleveland, then the workers in Dallas should make significantly more (not necessarily twice as much, though) as the ones in Cleveland. This incentivises moving: as a result, wages in high productivity areas and wages in low productivity areas wouldn’t see increased dispersion with perfect mobility because wage growth in productive cities will have to be somewhat replicated in the improductive ones to keep workers from moving.

But what if mobility wasn’t perfect? This means that moving to the productive cities is hard and costly - for example, because housing is very expensive. As a result, competition for labor between the productive and improductive cities is less intense - and wages grow much more slowly than they would in the latter. This would also result in employment in the productive cities not actually growing during productivity booms - there’s not enough people who can afford to move to take advantage of the results. Both of these effects compound, and as a result, the differences in wages keep adding up over time.

This seems to be what happened in the US from the 1960s to the present. Rich, productive cities like New York and San Francisco got too expensive for people in poorer, less productive areas to move into, and as a result wage and employment growth suffered. In turn, this created a ripple effect that led to economic growth being 36% lower than it should have been- which lowered GDP by 14% over the same period.

As a result of this disparity, the most productive cities didn’t contribute much to aggregate US growth - cities in the South did, simply because people could actually afford to move to them. But those aren’t as productive, so having the top performing urban cores be accesible would increase output by as much as 10%. Note that it’s not wholly unreasonable that the top-performing cities would be plagued by NIMBYs: San Francisco is so low-density because the results of that productivity are wholly captured by residents through higher salaries and higher property values.

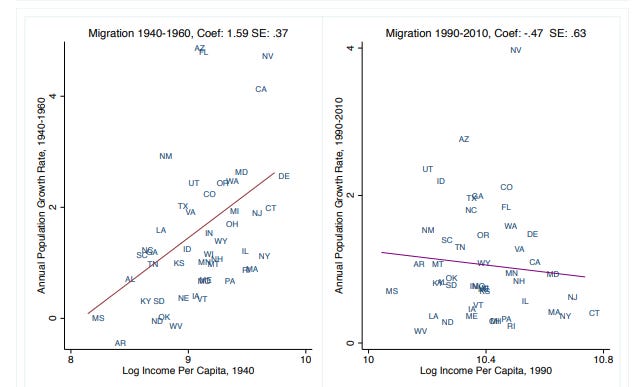

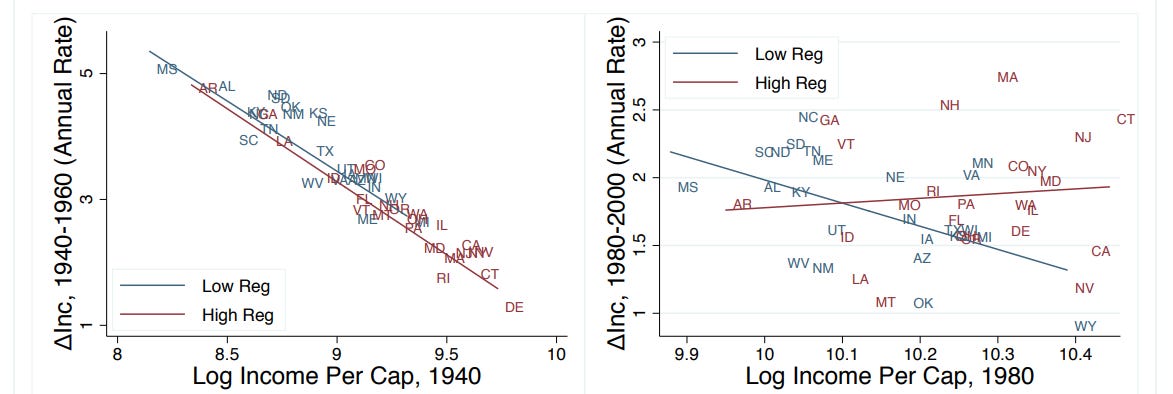

And remember how, in the debate over convergence, US states were cited by Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1992) as one of the main examples of income convergence? Well, convergence stopped literally at the same time as it was being argued - and you won’t guess why! (hint: the topic of the post). Since restrictions to the housing supply reduce labor mobility, convergence across US states stopped, basically because competition between productive and unproductive ground to a halt when productive cities decided to barely build any more housing.

Now, I think this understates the sheer impact of housing undersupply on growth. Firstly, because most studies on the matter only focus on a small sample of cities - so expanding it to a larger group would only boost the result, mostly due to cities having high restrictions in many places.

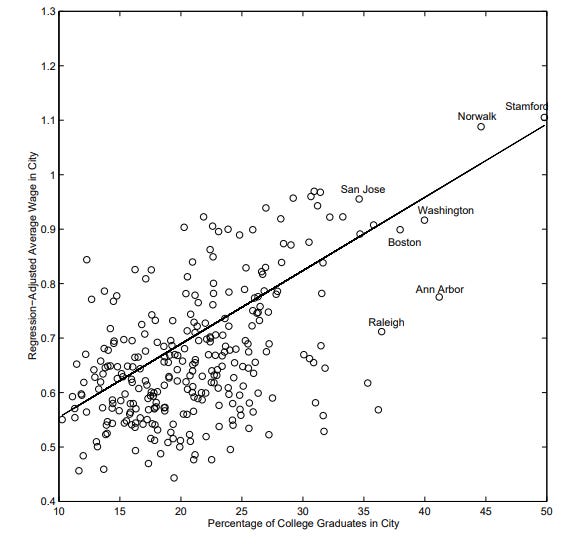

Secondly, because the main implication here is that observed productivity would have “trickled over” to other places and wages and incomes would be up. Now, cities have significant spillovers of knolwedge. To use the worst offender as an example, imagine what Silicon Valley would be like if the Bay Area wasn’t so prohibitively expensive for young innovators and other skilled professionals. Knowledge spillovers occur locally and between industries - so productivity across industries would have been even higher if there were more highly skilled people in cities, which in turn would have boosted output. There is a strong positive relationship between the adjusted earnings of the average worker and the percentage of college graduates, and in turn evidence points to a correlation between highly-skilled workers and productivity.

For instance, there is some evidence that states regulating land use extensively (New York and California, primarily) are a big reason why productivity growth in urban cores slowed, leading to the “Great Stagnation” of US productivity - tying into lower growth rates in general. If states were as regulated as they were in 2000, producivity would increase 30% more. If they were as regulated as they were in 1980, this figure would increase 69% faster - in line with the average during the strongest economic performances of the US. And finally, if US states had zoning 50% as loose as Texas (many metro areas don’t even have land use), total factor productivity would increase 85% faster - probably one of the best performances, in terms of growth, in the country’s history.

So not only did the NIMBYs make the US economy underperform compared to itself, they also made that underperformance be even worse than what would have happened if the economy functioned properly. An unfortunate side effect, perhaps, is that part of the reason why innovations are getting more and more costly is that, simply, not enough adequately skilled people are in the right places, despite the growing numbers of researchers.

The NIMBYs vs the Fed

In April of this year, Nobel Laureate Robert Mundell passed away. His main contribution to economics, for which he was awarded the profession’s top honor in 1999, was the idea of an optimal currency area: how “big” an economy should be to maintain a single currency, and what characteristics the parts of those areas should have. A good introduction to the idea comes from a 1999 Paul Krugman article on Mundell’s work:

The debate over how to define an “optimum currency area” is an endless one, but Mundell set its terms, suggesting in particular that a key feature of such an area would typically be high internal mobility of workers, that is, the willingness and ability of workers to move from slumping to booming regions. [emphasis added by Will WIlkinson]

Between different countries, shocks in demand in one country can’t be dealt with if it has the same currency (or a currency pegged to the value of the other currency) as a country that don’t have those shocks. Monetary policy in countries with currencies of fixed value is less effective at restoring employment, and more effective at simply boosting imports. But Mundell’s key insight is that countries have the same problem within their borders: a dollar in California is tied to the dollar in New Mexico, and Arizona, and Texas, and so on for all 50 states.

So multiple countries could benefit from having the same currency if their economies are similar enough and workers constantly move through them (for example, think of the BeNeLux countries in Europe); on the contrary, some countries might simply be too big and diverse to effectively manage a single currency. To quote Will Wilkinson (his piece on this issue is very very good):

Now, regional heterogeneity doesn’t necessarily mean that the territory of a nation-state is a sub-optimal currency area. As long as there’s enough “internal factor mobility” the system can adjust. That’s what Krugman was on about. (…)

But it is a huge problem when disused labor and capital just hangs around in downcast economies. If the Fed constantly finds itself in a position where it needs to both reduce unemployment in one region and check inflation in another — if its constantly stuck like Buridan’s ass between the bales of the dual mandate — that’s a sign that the regional economies of the common currency area are too different for monetary policy to work its magic across the whole economy.

In fact, the European Union and the Euro have this exact problem: the things that benefit the economy of, say, Spain don’t work so well for Germany. This also means that housing supply restrictions that reduce mobility and allos for slack make the Federal Reserve’s job harder: when California and New York are at full employment, Texas or Arizona might not be, given the employment and population growth dynamics of each. From Schleicher (2017):

… there is suggestive evidence that declining mobility, among other factors, can help explain some of the challenges the Federal Reserve has faced in setting monetary policy over the last forty years. The famed destabilization of the “Phillips Curve”—the concept that there exists an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment—since the 1970s does not show up in regional data. In other words, regional economies have continued to see relatively stable tradeoffs between inflation and unemployment—when unemployment goes up, inflation goes down—even as the national economy does not always exhibit this tradeoff. This suggests that the reason monetary policy has become a less successful tool for balancing inflation and unemployment is that regional economies have diverged from one another in important ways.

I won’t fully buy into the Phillips Curve argument, mostly due to lack of evidence in its favor, but it’s clear that at least some of it rings true - the US would have a more effective monetary policy, at least regarding employment, if the Fed didn’t have to put out one fire by starting another one.

It’s worth mentioning that the Fed also has a second mandate, price stability. Has the housing crisis made it worse?

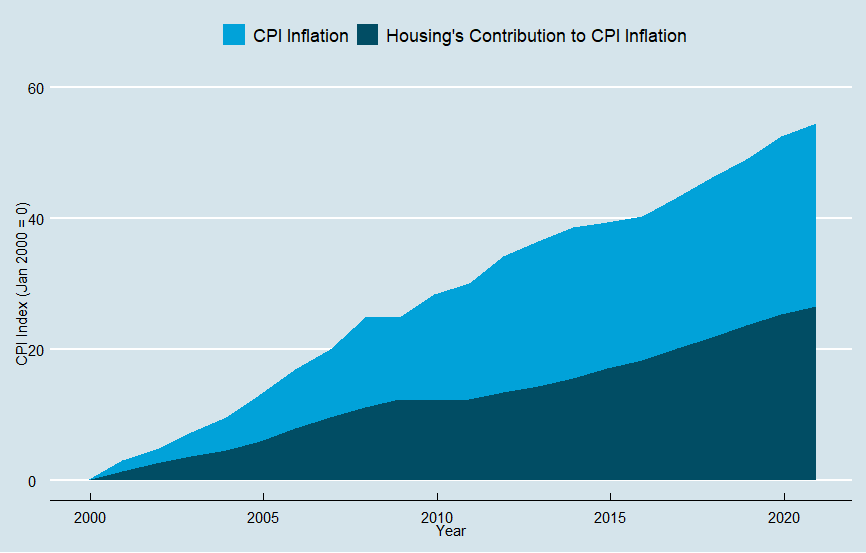

That’s right. Housing has not only gotten bigger and bigger as a share of all CPI expenses (from 33% of all items in 2000 to 42% in 2020), but it has also grown much much faster than the rest of the basket. As a result, housing inflation has accounted for almost half of all inflation in the US since 2000. This also makes monetary policy less effective, in its own way: just like used car prices and other wacky phenomena are making the inflation rate transitorily high in 2021, over-inflated housing costs make the CPI look bigger than it is. For example, it is estimated that cooling the asset bubble that led to the Great Recession would have necessitated interest rates of roughly 8% in the early 2000s - enough to dip the economy into recession.

So if the Fed wanted to fight inflation, it would have a target that works worse and is less good at actually showing how the economy works, simply because housing is getting extremely expensive very fast. Fun stuff!

The NIMBYs heat it up

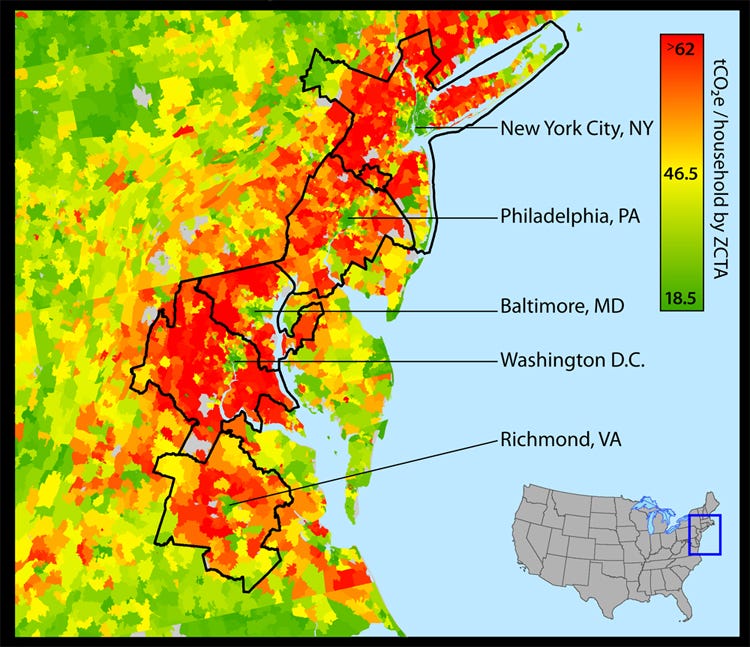

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges the world is facing, and the US has historically been the largest emitter of CO2 in both per capita and absolute terms. What about American lifestyles makes them so carbon-intensive? Besides from a mix of energy use that is carbon-heavy (for comparably developed nations, at least), almost 40% of US carbon emissions are related to residences and transportation. And these are not homogenous across the country: big cities in the West Coast and Southwest, such as San Diego, San Francisco, or Tucson; plus some cities in the East Coast like Providence, Boston, or Buffalo have the lowest emissions per capita (although some cities have very low emissions except for heating, such as New York), while urban centers in the South (and Minneapolis and Detroit, primarily due to heating and insulation) have the highest emissions.

In general, the most climate friendly cities are a weird mix, combining the temperate cities of California (which also require extensive amounts of driving) with colder cities in the North, both of which are efficient in terms of energy use and production. On the contrary, the most emission-heavy cities are all in the South, which combine high electricity usage, high amounts of driving, and dirty sources of energy. And newer homes in all cities are both more energy efficient but also require more driving, pointing to urban sprawl - which seems to be caused by restrictive zoning downtown.

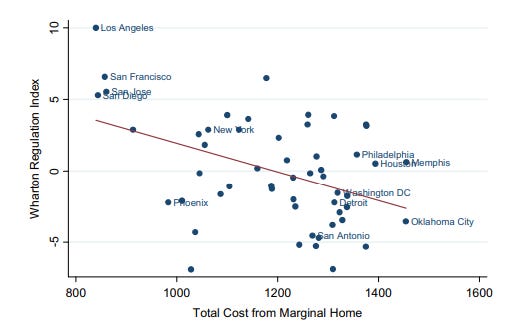

But there shows up a seemingly paradoxical problem: cities with more building are more carbon intensive (except Phoenix and Las Vegas) even withouth weighing for population, and there appears to be a strong negative correlation between land use restrictions and CO2 emissions per household. This appears to have two reasons: first, climate - most of the correlaion disappears after adjusting for weather. Secondly, selection: land use restrictions are strictest in the places with the lowest greenhouse emissions, and least binding in the places with the highest.

And the biggest consequence of land use regulations in many urban areas is sprawl, especially in the form of large suburbs. As a result, because urban cores have much lower emissions per capita than suburbs, restrictive land use policies increase emissions. There’s a few rare outliers, such as New York’s public transportation emitting so many greenhouse gases that it almost completely offsets the higher driving of the suburbs. In general, suburbs have much higher emissions for driving, less efficient housing, and less public transportation - not to mention a large chunk of new development is still happening in the South, which has less clean energy sources.

And sprawl interacts with climate in other ways. For example, California’s bad housing regulations have driven the state to build further and further from city cores, with new developments that are so far away they simply extend right in the middle of areas at heightened risk for wildfires.

The NIMBYs made their slice bigger

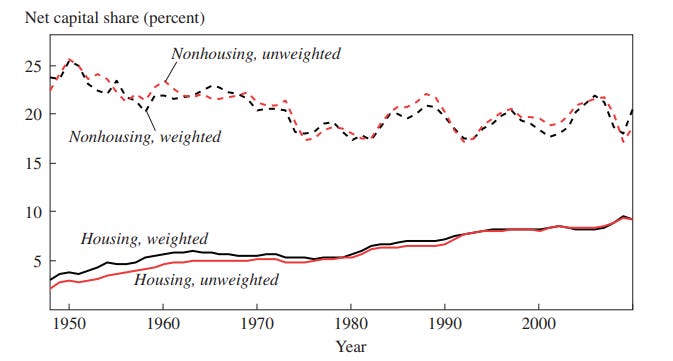

Thomas Piketty’s 2014 book “Capital in the 21st Century” started a global conversation on income and wealth inequality and instigated a whole bunch of academic research on the subject. Its key assertion: the share of returns to capital as a percentage of national income, in the US and many other developed countries, has been increasing - and mostly benefitting the rich, who own the capital the returns acrue from.

According to Rognlie (2015), the centerpiece of this story is housing. If you look at the share of national income that capital has, and divide it between housing and everything else, the non-housing part remains roughly the same (actually gets a tiny bit smaller) while the value of housing increases. There can be some caveats, mostly due to the wacky ways housing income is estimated (you can’t really directly measure how much someone “profits” from owning a house, except from what they’re saving in rent), but in general, the gist is this: a big driver in the story Piketty pitches, of growing income inequality, comes down to higher and higher returns on land and structures.

I’m going to be extra careful and give a lot of leeway to the more traditional Piketty view of inequality - not to mention that this only touches on capital income and not labor income. But it’s also hard to ignore that a noteworthily large part of the problem seems to be caused by inflated housing costs, which are primarily caused by restrictions on new construction. Another point in favor of this explanation is that, if you divide the contributions to all housing capital income between states that have strict restrictions on building and states that don’t, you see that housing capital is only getting bigger because of the states that aren’t building houses.

Plus, we’ve already explained how restrictive zoning priced “normal” people out of the highest productivity areas in the US. Due to producitivity growth being mostly beneficial to people based on where they live, if only upper income people can afford to live in the most productive cities, they’ll reap most of the benefits. Plus, renters receive less in benefits than homeowners due to disparities in housing costs, as they have to pay higher rent (they still come out ahead as a result of higher wages, generally), but homeowners both get the higher wages and higher property values.

Finally, there’s the issue of race. I have already mentioned, more than once, how homeownership is a huge chunk of the racial wealth gap. For instance, houses in black-majority neighbourhoods are worth substantially less than similar structures in white or integrated neighbourhoods. The relationiship between housing and racial inequality could fill a whole post on its own, given how complicated it is.

There is one additional source of inequality: education. From Rothwell (2012):

Nationwide, the average low-income student attends a school that scores at the 42nd percentile on state exams, while the average middle/high-income student attends a school that scores at the 61st percentile on state exams. This school test-score gap is even wider between black and Latino students and white students. (…)

Across the 100 largest metropolitan areas, housing costs an average of 2.4 times as much, or nearly $11,000 more per year, near a high-scoring public school than near a low-scoring public school. This housing cost gap reflects that home values are $205,000 higher on average in the neighborhoods of high-scoring versus low-scoring schools.

There are significant lifetime income gains attached to attending a high-scoring school, not to mention a much higher likelihood of attending college. In an incredibly dispiriting example, three of the five widest gaps in performance between low and high income students are in Connecticut - one of the most restrictive housing markets in the US. Generally, Northeastern cities are the most uneven in performance, and Western cities the most even (El Paso, Texas has the smallest gap in the US).

Access to high-scoring schools (generally higher quality) is also closely attached to homeownership, and the best schools are disproportionately near very expensive areas. The median home in one of these costs 11,000 dollars more than a house near a worse school - very close to the average tuition of a private school, in fact. Yet again, this gap is widest in Northeastern cities (and also Los Angeles) and smallest in the West (and Florida), with Boise having the lowest housing cost gap. And these housing value gaps are directly linked to zoning - metro areas with the most restrictive land use policies have housing near high-scoring schools be 40% to 63% more expensive.

Basically, the pipeline here is: upper income person moves to expensive house, sends children to good schools, gets richer due to housing inflation, gains the most from productivity growth, children inherit valuable house, repeat. Low income people, meanwhile, have to get by with the worst schools, the least valuable homes, and the smallest gains from productivity.

Conclusion

NIMBYs made housing more expensive in the most vibrant, most productive cities in the United States. That’s bad enough. But the fact that housing became so much more expensive also cost the economy a lot; reduced potential future innovation; made full employment less likely; heightened inflation; worsened climate change; and worsened income and racial inequalities. All of these problems play into each other.

Wanting to build more houses isn’t just about making housing cheaper. It’s also about preventing annoying busybodies from gaining at the expense of the entire economy. Restrictive zoning isn’t a local issue, it’s a national issue, because it has enormous externalities for basically everyone else. Most zoning has to be done at the local level, because it wouldn’t really make sense to decide what to do with a vacant lot in Tacoma in the US Senate, but municipal authorities have clearly shown they can’t be trusted with the power to set land use rules - the states and the federal government have to step in and intervene, because the NIMBYs have used their political power over city councils to not only grow their size of the pie, but to make the pie smaller and less sustainable.

Sources

Housing and growth

Hsieh & Moretti (2019), “Housing Constraints and Spatial Misallocation”

Hsieh & Moretti (2015), “Why Do Cities Matter? Local Growth and Aggregate Growth”

Bryan Caplan (2021), “Hsieh-Moretti on Housing Regulation: A Gracious Admission of Error”

Ganong & Shoag (2017), “Why Has Regional Income Convergence in the U.S. Declined?”

Parkhomenko (2021), “Local Causes and Aggregate Implications of Land Use Regulation”

Glaeser, Kallal, Scheinkman, & Shleifer (1992), “Growth in Cities”

Glaeser & Saiz (2003), “The Rise of the Skilled City”

Moretti (2003), “Human Capital Externalities in Cities”

Matt Clancy (2021), “Innovation gets mostly harder”

Will Wilkinson (2021), “NIMBYism and the Externalities of Non-Development”

Housing and macroeconomics

Will Wilkinson (2021), “America Isn't an "Optimum Currency Area"

Schleichter (2017), “Stuck! The Law and Economics of Residential Stagnation”

Joseph Politano (2021), “Fight Inflation - With Housing”

Housing and climate change

Stern (2008), “The Economics of Climate Change”

Glaeser & Kahn (2010), “The greenness of cities: Carbon dioxide emissions and urban development”

Kahn (2009), “Urban Growth and Climate Change”

Housing and inequality

Rognlie (2015), “Deciphering the fall and rise in the net capital share”

La Cava (2016), “Piketty’s rising share of capital income and the US housing market”

Perry, Rothwell, & Harshberger (2018), “The devaluation of assets in Black neighborhoods”

Rothwell (2012), “Housing Costs, Zoning, and Access to High-Scoring Schools”

This was great. Thanks, person I found on Twitter.