Why is the American welfare state so small?

The US spends far less on welfare than other developed nations. Why?

How small is the welfare state?

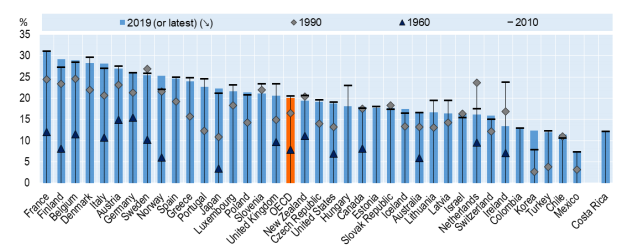

Traditionally, governments are seen as having three main functions: providing public goods (such as infrastructure or defense), stabilizing the economy, and redistribution from the rich to the poor. In developed countries, public goods and redistribution tend to be much bigger than stabilization, and redistribution has grown significantly, from public good provision being twice as large as redistribution spending in the 1960s in the OECD to them being equally big today. As a result, considering countries shouldn’t spend significantly more on stabilization than they used to, redistribution doubling in size should explain most growth in government as a share of GDP.

The average European country has spending make up 48% of GDP, while in the US it is closer to 35% - and the composition is different, with defense spending being much bigger in the US and transfers to households being half the size of its Old World counterparts. Part of the gap in defense spending comes from the US “taking over” the defense of certain countries, many of them in Europe, which would mean spending would be even lower without them free riding on American military might. The US also has slightly higher public investment, but that’s neither here nor there.

Additionally, the US welfare state is much more weighed towards pensions and healthcare, especially for the elderly, and is significantly smaller regarding unemployment benefits or family support (which was basically non-existent until this year). And spending probably overstates the difference, because American healthcare is incredibly expensive, twice more than other developed nations. Finally, the US also relies very heavily on labor requirements, which aren’t particularly effective at increasing employment but do decrease access to the programs.

If you count private social spending (i.e. personal spending on private pension funds, donations by charities and NGOs, and healthcare contributions), then the US is the second biggest spender, after France. Yet again, this measure is inflated by outstanding healthcare costs (in the public and private sectors).

It is measurable, though, that Americans spend much more on charity than other similarly wealthy nations: while the average American donated 691 dollars to private charities, the average European only gave 57. This could, however, be caused by Europeans considering that welfare trumps private charities in effectiveness, and by charitable donations making recipients inelegible for welfare transfers. So a first reason why the US spends comparatively little is that Americans think private charities are more effective at aiding the poor than the government, and thus “vote with their dollars”.

Since all spending is ultimately paid for by taxes, an additional consideration is brought up: the US has significantly lower tax burdens than Europe, especially on consumption. So a second idea why the welfare state is smaller is that Americans value social spending as highly as Europeans, but simply dislike the taxes necessary to pay for it so much more that they’d rather not have it.

A final issue to consider is openness. More open economies have bigger governments, because, since external shocks are more likely, then the government must provide bigger stabilization programs (that frequently overlap which redistribution). This effect is, additionally, much bigger for small economies. The US is a big economy and much less open than Europe or many small OECD members, which probably might explain some of the difference - but the US also has a more volatile economy.

Why do people (not) want welfare?

Spending is, ultimately, paid for by taxes. Since redistribution helps the poor, it wouldn’t make sense to tax them to pay for it, so it’s funded with taxes on the not-poor. In consequence, you should initially expect the rich to more or less oppose redistribution, and the poor to support it.

But some people are born poor and later stop ceasing to be poor, while others who aren’t poor get hit by hard times - so maybe the relationship is more complicated. In addition, people can think being (not) poor is (not) their “fault”, so besides from actual social mobility, another interesting factor to consider is perceived social mobility, i.e. how likely people think that they are to be rich(er) in the future. Empirically, being actually socially mobile is not that predictive, while current income is - and expectationsof mobility are crucial. In other words, people thinking they’re going to be richer if they work hard means they’re less likely to be altruistic towards the poor, regardless of this being or not the case (for example, the US was as socially mobile as Germany between 1984 and 1999, but had a much smaller welfare state anyways).

A second consideration is that redistribution is likelier not just when people “like” the poor more, but also when the poor are more represented in the political process. So many European nations have highly proportional political systems, while the US has very undemocratic institutions, like the Senate and the Supreme Court, wield significant power. And the lack of proportionality of the American political system also systematically deprived radically pro poor parties of oxygen for electoral participation. Finally, it seems Americans are far more likely to support “punishment”, for example in their love of the death penalty, their popular support for war, or their willingness to cut back on aid to the poor

So far, it seems that the American welfare state might be small because Americans dislike taxes significantly, because Americans like charity more than welfare, because Americans are likelier to think they can become rich in the future and place a bigger emphasis on hard work veruss luck, because Americans are less altruistic towards the poor, and because the American political system is less representative. The ones about taxes and charity probably go hand in hand and have to do with deeply ingrained elements of their “national character”, and so does the seeming obsession with hard work. But the last two, which seem to be stronger at actually explaining this, are… odd. Why is the American political system so undemocratic? And why are Americans so reticent to want to support the poor?

The R word

In the US, interpersonal altruism seems closely linked to race, for a variety of reasons (racism is a really complicated phenomenon). Since poor Americans are disproportionately likelier to be non-white, and US has a significantly less ethnically homogenous populations than Europe for a number of historical factors, it follows that Americans have less sympathy towards the poor - which gets even worse considering that Americans also believe that working hard can get you out of poverty. There is some empirical evidence suggesting that communities where welfare recipients are of the “majority” race have more support for redistribution than ethnically heterogenous communities. Plus, historically, most instances of anti-democratic suppression in the United States happened against ethnic minorities, such as Jim Crow laws that restricted the franchise.

And why are ethnic minorities, especially black people, so much poorer than whites? Firstly, there is an income gap between white and black workers, which has a variety of explanations that are beyond the scope of the post and also are clearly endogenous to race (look at last week’s wage gap post for a similar piece about the gender wage gap). Secondly, there seems to be a negative effect from the disproportionately higher prevalence of single-parent households and large scale incarceration, but the gap is also present at the highest black income percentiles, weakening this explanation. Finally, the assets of black families seem to be less valuable: housing wealth is lower (due to lower home values and lower home ownership), and “worse” investments.

One of the biggest reasons why black households have less valuable housing is the practice known as “redlining”, where the government insured mortgages for the most “credit-worthy” areas - which were overwhelmingly white suburbs, while the “dangerous” areas were minority communities. In addition, many urban infrastructure projects, such as highway expansions, were frequently built into cities by demolishing minority neighbourhoods under the pretext of “slum clearance”.

Conclusion

It appears that a combination of more dislike for high taxes, greater emphasis on hard work and self reliance, and less trust of the government versus private actors (especially charities) are part of the reason why the American welfare state is smaller than the one in comparably rich nations. Moreover, racially polarized politics are the biggest factor, since disproportionate poverty among ethnic minorities results in less support for redistribution from racially “intolerant” whites.

While racially neutral populism hasn’t been a particularly viable coalition in the US (for example, George Wallace’s anti rich platform was defeated by the KKK-endorsed John Patterson in 1958), many politicians used anti-welfare language to convey racially charged policies. Southern members of both parties tended to use that strategy, but the national Republican Party made it mainstream with the “Southern Strategy” of the 1960s. To quote one of its key strategists, Lee Atwater (the censored word is a racial slur. You can probably figure out which one):

Y'all don't quote me on this. You start out in 1954 by saying, "N*****, n*****, n*****". By 1968 you can't say "n*****"—that hurts you. Backfires. So you say stuff like forced busing, states' rights and all that stuff. You're getting so abstract now [that] you're talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you're talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is [that] blacks get hurt worse than whites. And subconsciously maybe that is part of it. I'm not saying that. But I'm saying that if it is getting that abstract, and that coded, that we are doing away with the racial problem one way or the other. You follow me—because obviously sitting around saying, "We want to cut this", is much more abstract than even the busing thing, and a hell of a lot more abstract than "N*****, n*****". So, any way you look at it, race is coming on the back-burner.

If you think the American welfare state should be somewhat larger, there’s three issues to focus on. The cultural aspects (not liking taxes, etc) are already hard enough to tackle, but still not as hard as figuring out how to avoid the racialization of the benefits. What size the welfare state should be and how it should function isn’t something I’m qualified to say, but it’s vital to acknowledge that simply promising “free money” isn’t enough when there’s a big cultural reluctance to expanding welfare already.

It is somewhat encouraging that 2020 and 2021 had such big expansions of government assistance during the pandemic, since many voters would have personally benefitted from them at a time of hardship - so perhaps actual experience with the systems of welfare and assistance would be a plus in the fight to expand benefits (although the tax aspect would, sadly, remain unchanged).

Sources:

Alesina, Glaeser, & Sacerdote (2001): “Why Doesn't the US Have a European-Style Welfare System?”

Alesina & La Ferrara (2005), “Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities”

OECD (2011), “OECD Science, Technology and Industry Scoreboard 2011”, Trade Openness

Alisprantis & Carroll (2019), “What Is Behind the Persistence of the Racial Wealth Gap?”

Aaronson, Hartler, & Mazumder (2020) “The Effects of the 1930s Holc 'Redlining' Maps”