Does rent control work?

A year ago, Argentina capped rent increases. It didn't work. Have other places been more successful?

Rent control at the end of the world

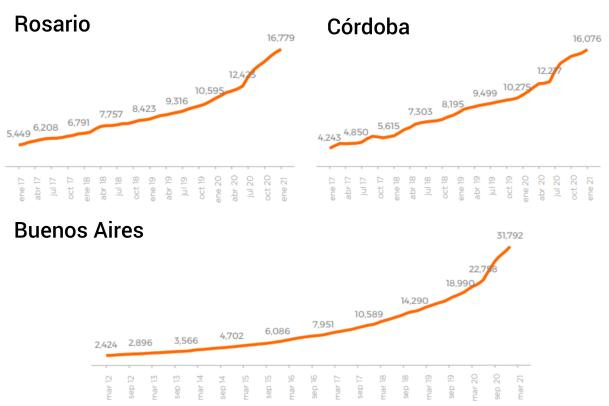

On June 11, 2020, the Argentinian government passed the "Rent Law”, which altered the regulations concerning rentals. The biggest changes were the prohibition of updating rent more than once a year, and the obligation to update it according to a pre-set index specified by the Central Bank. Additionally, the duration of contracts was extended from two to three years, upfront payments and deposits were reduced, all maintenance duties were offloaded to the owner, and a number of registration requirements were imposed. As you can see below… it didn’t make rent cheaper.

The one variable not mentioned anywhere in the law was initial rent, i.e. how much new leases would charge. You don’t need a PhD from Harvard to see where this is going: almost all owners who didn’t have a lease increased their asking prices significantly to cover for the deterioration in incomes due to high inflation (about 3.5% a month since May of 2020).

The relative price of rent (i.e. an index obtained by dividing the montly new rent payments index the City of Buenos Aires keeps by the average City of Buenos Aires-specific CPI) increased substantially as a result, growing by 16% from June to December. This means that rent got 16% more expensive than the average product in the CPI - a big feat considering late 2020 and early 2021 have had roughly 4% monthly inflation (for reference, a full year of such high price increases would yield 60% inflation).

Plus, between 2007 and 2020 (before the pandemic), rents actually got cheaper after adjusting for inflation, by 57% in the City of Buenos Aires and by 25% in other major cities. A large part of this change was due to inflation growing much faster than rent, owing to, ironically, no adjustment in contracts. A big part of this decrease actually happened in 2018 and 2019, big recession years, where real rent decreased by 20 points, mostly lagging behind a cumulative 90% inflation rate.

In addition, right at the start of the pandemic the authorities froze rent and banned evictions, which was eventually extended until July of 2021, when the first update set by the rent control act will happen. Due to a very deteriorated economy, the average tenant owes between 50,000 and 70,000 pesos.

Both of these made rentals a much less attractive investment for their owners than just sellling the homes - which is shielded from inflation, since most real estate sales in the country have been done in US dollars since the 1980s. As a result, the supply of apartments for sale increased, and the supply of rentals decreased.

Additionally, this also affected other cities in the country, such as Cordoba and Rosario (the ones I have data for, at least). Rent increased 35% in Rosario, 32% in Cordoba, and about 34% in Buenos Aires between April 2020 and January 2021, while the price of a square meter (in USD, so no inflation involved) dropped 3% in Rosario, 10% in Cordoba, and 10% in Buenos Aires in the same period, which is at least consistent with a supply-side glut (there could also be a scarcity of demand due to foreign currency rationing or pandemic halts, however, making this side much more dubious).

Mister Mayor, bring down these rents

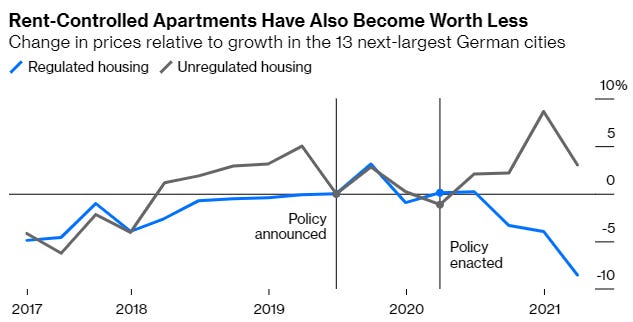

There was also another national capital starting with “B” that tried rent control recently: Berlin. In February 2020, Berlin’s government introduced rent controls on all apartments built before 2014, splitting the market in two. Instead of comparing rents in Berlin 2020 to rents in Berlin before, researchers (later quoted by Bloomberg, considering their research is in German) compared Berlin to 13 other German cities, to see if rents were getting more or less expensive versus the rest of Germany.

When measured like this, rents in the regulated sector of Berlin grew about 60% less than in the rest of Germany, while the unregulated sector grew 9% more rapidly. Now, this doesn’t mean rents in Berlin were 60% lower, but rather that they increased at a slower pace. For example, if rents increased 2% in the other cities, Berlin’s rent grew just 0.8% in the regulated sector and 2.2% in the unregulated one. This seems like a desireable effect, but it should be considered that rent controls benefit current tenants exclusively (by definition, in fact) and their effects might be more negative on future tenants if the supply of apartments is reduced in such a degree that future rent is increased.

In addition, the unregulated sector saw faster rent increases than other German cities, which wasn’t actually the case before 2020 (it also wasn’t for the regulated sector, but that’s neither here nor there).

And a problem comes up here: the value of rent controlled apartments decreased, whilst listings for renting became more rare as listings for sales became more frequent. This could point to the fact that tenants who lived in rent-controlled apartments weren’t moving out, and if they did the owners didn’t seem to rent them any longer and instead sold them to avoid the hassle. On the contrary, unregulated apartments became more valuable and their rental listings grew in line with other German cities, but listings for sales grew equally significantly more than both other German cities and rent-controlled apartments, possibly pointing to investors focusing on them to obtain higher profits.

There might be other factors influencing decisions in real estate investment, however, and causation cannot really be drawn - just correlations. Plus, the policy was struck down as unconstitutional by German courts recently, so the full effects of these policies hadn’t been observed. However, it seems likely that the impact on supply on the more affordable market would have spilled over into the unregulated one, pushing up rents even further.

What does the economic evidence say?

One of the oldest, most econ 101 sources on rent control is Friedman and Stigler’s 1946 essay “Roofs Or Ceilings: The Current Housing Problem”. Even in 1946, San Francisco had a housing problem: rents were very high and homes were scarce. This experience was compared to right after the San Francisco fire of 1906, which destroyed a large amount of buildings, proving to be a “natural experiment” (i.e. caused by chance) of a shortage of homes. Their main argument was that allowing market forces to dictate rents would result in enough construction and incentivize people to use space rationally, leading to plentiful housing for all income levels. On the contrary, rent controls would result in insufficient construction as long as they were in place (negating their very effects), inefficient use of space, and inadequate allocation of apartments. Obviously, I wouldn’t trust a 75 year old paper without much on the way of data, even if Friedman (I don’t know about Stigler, really) was a super smart guy. So let’s find some other evidence.

From 1970 to 1994, Cambridge, MA had strict controls on rents for buildings built before 1969. However, unlike other cities, it didn’t allow landlords to update rents after their tenants moved out - incentivizing the removal of homes from the rental stock altogether. During the time this regime was in place, it seems that it reduced investment in amenities (i.e. in housing improvements, etc) and disincentivized people from moving out of rent-controlled dwellings and into other places that might best suit their preferences (bigger or smaller, etc). In 1994, this measure was narrowly abandoned. As a result, the value of decontrolled properties (i.e. houses that were controlled before 1994 but were no longer) increased by 45% by 2004, and so did unregulated properties in nearby areas. In fact, there was a clear correlation between property appreciation after decontrol and intensity of controls. While decontrol directly resulted in earnings of $300 million for landlords and property owners, property values increased by another $1.7 billion - implying large negative externalities to the property values of other homeowners, nearly 6 times the size of the benefits to tenants from lower rents.

There is a (somehwat) similar story in San Francisco, which instituted rent controls in 1979 and reformed them in 1994- by imposing controls on more housing units, but in such a way that very similar buildings could (not) be affected by them basically at random. Firstly, it would seem that tenants of rent-controlled buildings value this, since they are 19% less likely to move out of them; and many people in rent controlled buildings were fairly likely to move out of San Francisco if rents weren’t capped, which is an especially big effect for minorities. This effect wasn’t as present in the most expensive areas, because SF did allow post-eviction rent hikes, so not evicting tenants has high opportunity costs. And unlike Cambridge, San Francisco did not have such a clearly negative correlation between rent controls and investment in amenities - but because property owners made big investments to turn their rent-controlled dwellings into condominiums or other types of housing that didn’t have regulated rents. The 1994 law, thus, resulted in a supply of rentals that was 15% lower and in 25% fewer people living in rent-controlled buildings, mosty due to turning those units into condos or redeveloping them into new housing that wasn’t rent-controlled. So new housing = more housing = good, right? No. This wasn’t market-rate housing, but rather uber-expensive luxury housing that catered to high-income individuals. As a result, San Francisco’s rent control resulted in a lower housing supply and in more expensive homes being built, both contributing to higher rents and, ironically, negating rent control’s deterrence of gentrification and displacement.

When New York has had some degree of rent controls since the 1960s, basically the same thing happened: less supply, lower investment in amenities, lower housing prices. Plus, rent control didn’t benefit low-income people any more than upper income people, and there wasn’t really a statistically significant effect on minorities versus whites, even after adjusting for the fact minorities were more likely to be in rent controlled units. Plus, housing seems to have been very badly allocated between individuals, costing about $200 to general welfare per apartment per year. This might seem small, but given the number of apartments in New York, it adds up to about $500 million a year.

Conclusion

In the end, it seems that rent control has positive effects in the short term and negative ones after a while. On the positives side, it can (outside of Argentina, it seems) decrease rents and deter displacement, especially for lower income residents of color. On the negative side, it seems to reduce investment in upkeep, reduce new construction, lower property values, incentivize higher turnover in rentals, incentivize taking rentals off the market, incentivize converting rentals into high-end unregulated properties, and ultimately raise rents in the long run.

Of course, as stated in a previous post, building more housing alone isn’t a solution. Well-designed rent control could be a way to stabilize a market, or to make upzoning more politically viable. However, it is a bandaid and cannot on its own make housing affordable. In the end, it seems that the welfare gains to the “insiders” of rent control are far outpaced by the losses to everyone else.

The main problem with rent control seems to be that it’s a static tool for a dynamic problem - rents aren’t high in this exact moment because of a decision made right now, but rather because of longstanding housing market patterns. So controlling rents can decrease them now for incumbent renters, at the detriment of future renters (and landlords, but nobody cares about them) due to the negative effects on supply.

Sources

Buenos Aires

“A Bad Year for Tenants” (2021), Federico González Rouco, Seúl Magazine - in Spanish

Zonaprop: real estate indicators for Buenos Aires, Rosario, and Córdoba- in Spanish

Berlin

“Berlin’s Rent Controls Are Proving to Be a Disaster” (2021), Andreas Kluth, Bloomberg.

Economic theory

Friedman & Stigler (1946) “Roofs Or Ceilings: The Current Housing Problem” - note: I don’t think the FEE, in general, is a reliable source. However, they were the only one that actually let me access this paper.

Diamond (2018), “What does economic evidence tell us about the effects of rent control?”

Sims (2007), “Out of control: What can we learn from the end of Massachusetts rent control?”

Glaeser & Luttmer (1997), “The Misallocation of Housing Under Rent Control”