The world’s favorite right-wing unmarried “dog dad”1, Javier Milei, is currently on the discourse radar again: this time, because of a viral tweet claiming that rents decreased 40% and the supply of rental properties increased 300%. True? Obviously, no. There wouldn’t be a post otherwise. But how and why is that not true?

That's not the truth, Ellen

Let’s dig slightly deeper. The numbers, by themselves, are correct: as reported by Reason Magazine (the likeliest source for this claim), properties listed on the “Zonaprop” property listing site (kind of like Zillow) did increase by that amount, and their price did fall by that amount within a year. But the claim does hide some interesting dynamics around the housing market in Buenos Aires which American observers wouldn’t really be able to follow.

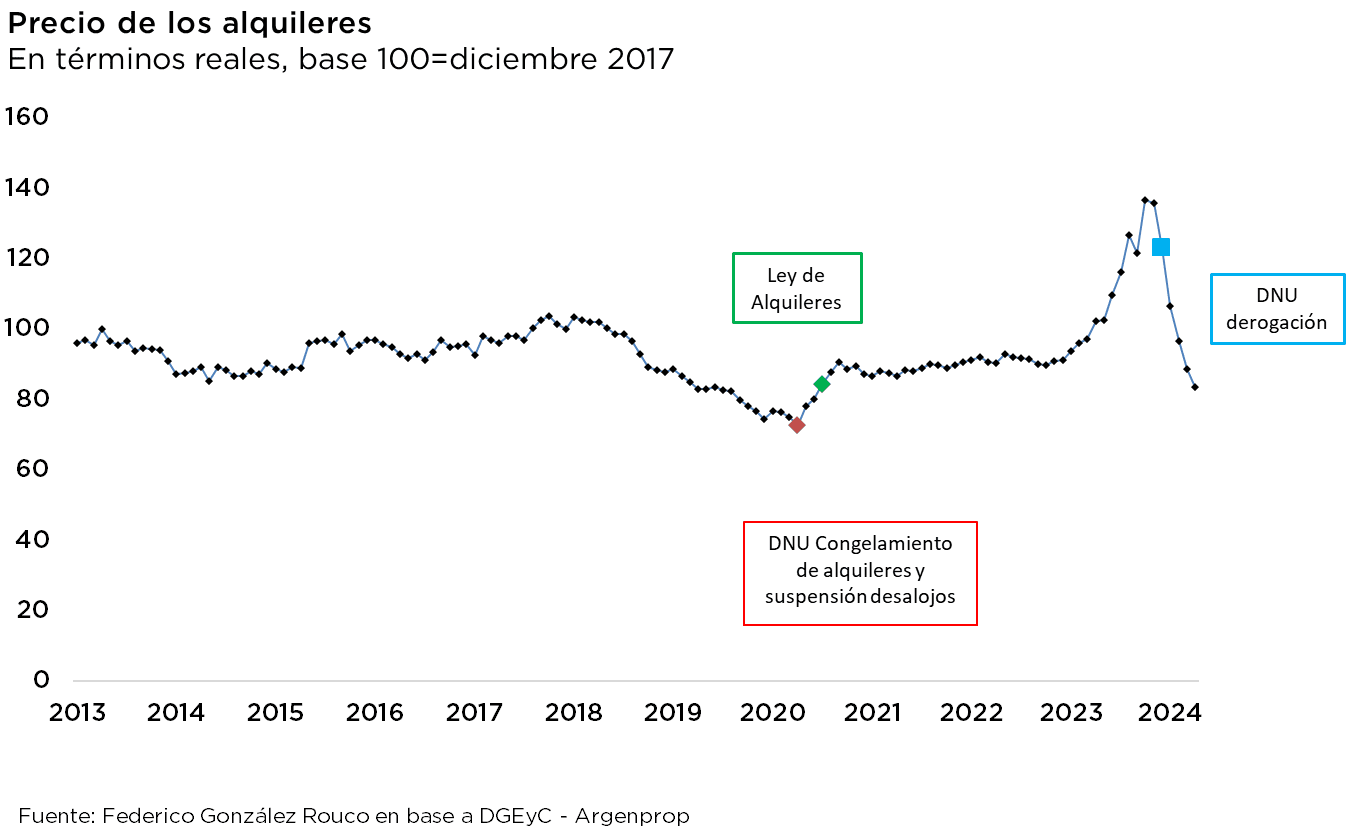

Let’s start by looking a bit more closely at the rent control law. It was instituted in 2020 and basically made it so rental contracts had to be longer, more strictly regulated, and had to be indexed to inflation following a certain formula. Surprising basically nobody, rents shot up after the law passed (around 20%), and the supply of apartments for rent shrank to some extent, while the number of listings for sale increased. There’s two big caveats here. The first is that, if you look at the chart above, you see that real rent decreased for two years in a row before rent control was passed - which was less due to any supply or demand related issues, and more to do with the fact that inflation increased by 30 percentage points between February 2018 and August 2019. The rent control law did allow a good excuse to claw back two years of back-to-back losses in a single point in time, and then rents remained somewhat stable until 2023. The second caveat is that rental supply had been decreasing pretty steadily between 2015 and 2019; the reasons for this are, not surprisingly, complex, but it’s pretty plausible that macroeconomic volatility, accelerating inflation, and structurally low rental to price ratios in this period (mainly because prices are measured in US dollars, which mean that they move in the opposite direction as rents when the exchange rate moves), which meant steadily lower profits throughout the period. Regardless of this, a really important fact to note is that a lot of rental supply in Buenos Aires is just not registered with the government, and that rent control in a context of inflation that doubled every year for three years in a row meant that a lot more contracts than usual were going to be settled informally. So, beyond the increase in properties for sale versus for rental, most of the effect on supply could be seen in an increase in the quantity of informally rented housing - for example, this 2023 survey of renters finds that 50% of renters had an informal lease, compared to 47% in 2020 and, 60% of renters saw illegal increase in rental prices, which again shows low compliance and lack of enforcement.

And here comes the main problem for the comparison - 2023 was just a uniquely bad year for the housing market. If you look at, for example, this indicator of affordability for workers 18-242 as an example, you see that the share of income needed to make rent increases from the mid 50s in 2022 to an eye-popping 103% in 2023, and decreases back to 52% by the third quarter of 2024. Housing affordability in 2023 reached historic lows because of three somewhat related factors: the first is that supply completely cratered for most of the year owing to extremely high inflation (over 10% per month for most of the year) and extremely high political and macroeconomic uncertainty in a very closely contested presidential election. This meant, secondly, higher prices both directly, and indirectly via more frequent and more elevated price adjustments given the lack of (again, formal) alternatives for renters in a low-supply market. And thirdly, high political and economic uncertainty translated itself as a large gap between the official and parallel market exchange rates, which meant that the country was very attractive for tourism - resulting in a surge in Airbnb listings and thus in reduced supply and, therefore, higher prices (again, it’s plausible that some of these listings were just covert rentals for locals, which just plays into the factors mentioned above). And the depressed economic picture, with surging inflation and GDP contracting 1.6% in the year, meant that real wages also suffered, resulting in steep decreases in incomes.

Fast forward to 2024, a year after rent control was repealed. Beyond that regulatory change, you had two major changes: first, that inflation was decreasing from 25% a month in December 2023 to 2% a month, and that the gap between official and parallel rates shrank substantially (from over 100% to the 10-20% range), which meant that, given high cumulative inflation and low cumulative currency depreciation, the exchange rate became a lot less attractive for foreign tourists and thus the profitability of Airbnbs decreased dramatically. This, paired with deregulation of contracts that did incentivize contracting formally, increased the supply of properties in the formal rental market and managed to claw back the exorbitant 40% increase in real rents in 2023, plus a 10% extra. However, the deregulation of contracts also allowed for a separate channel of price adjustments: building maintenance fees and miscellaneous shared expenses (known colloquially as expensas, or just expenses) increased sustainably and substantially since 2023 (the cases listed are in Córdoba, the country’s second largest city, but the situation seems similar in Buenos Aires: rents increased 45.5% in nominal terms, and expenses increased 126.6%), offsetting some of the real decrease in direct housing costs with increases in mandatory fees and contributions to the small landlords that dominate Argentina’s rental market.

I think that, in general, when talking about housing affordability we tend to focus on just one aspect, prices, but the other factor that’s equally important is wages: real earnings in Argentina have fallen approximately 20% since 2019, which means that the significant increases in housing costs in 2020 and 2023 resulted in an enormous crunch in disposable incomes - in 2024, real income was lower than in 2023 in large part because the economy continued being depressed and higher costs in utilities, expenses, transportation, and just all-around inflation put a lot of pressure on budgets. Wages did, to be fair, recover from the enormous pit they’d sank into in 2023 and early 2024, but did not manage to bounce back all the way and the recent picture is not positive, with a stalling labor market and rents growing somewhat above inflation in the City.

So, in general, I would say that repealing rent control regulations was a good thing because they had distorted the rental market and pushed listings off the formal sector and into informal directions (which, paradoxically enough, results in lower market prices but higher costs considering that formality has benefits in case of legal disputes), and rental supply does seem to have increased beyond recovering from the 2015-2023 secular drop, which has had an effect of a drop in rental prices beyond mean reversion. However, I think that claims that rent “fell 40%” are (while, yes, in a literal sense factually correct) exaggerated and a bit dishonest, and obscure the reality that housing affordability improvements were heavily influenced by broader macroeconomic factors, and also have an uglier “subplot” in stagnating real wages that put a limit on how much the supply increase can improve affordability outcomes, which are back to pre-crisis but post-rent control in relationship to earnings.

I also think that this gives us an opportunity to look at a slightly deeper question: what is housing policy even doing that, even before rent controls were ever implemented, affordability outcomes were that bad: the share of income spent on housing increased from 25% in 2015 to 32% in 2019 to 35% in 2021, and probably grew further in 2022 and did not improve in 2024. Plus, the percentage of people in the country who rent has basically doubled in the last decade, and intergenerational “escape from renting” is very low. So what are we even doing?

I’m green da ba dee da ba di

The question of “why is it so difficult to buy a home in Argentina” is, I think, a lot more interesting than the question of “is rent control bad” (mostly, yes). The most obvious issue is that housing transactions are denominated in US dollars and conducted basically entirely in cash, which means that to buy a house first you need to save up in USD “in your mattress”, which involves both significant transaction costs and significant risks. But why does it happen this way?

Let’s take a step back. Housing is the most important purchase most households make, and on average is worth multiple times the annual income of most families. In order to make smoothing payments easier, countries thus developed housing credit systems where you borrow money from a bank, use it to buy a house, and then pay the bank back over multiple decades. There are obviously many specificities, such as whether the bank or you owns the house before you pay it off, whether you choose a fixed or variable interest rates, and many regulatory aspects such as how much of an initial payment you have to put down. This means that, without a developed system of housing finance, housing affordability becomes a major issue precisely because most people can’t save up for decades to make an all cash payment, especially not in developing countries. To put some perspective into this, mortgage credit in Argentina is under 1% of GDP; in the US, it’s roughly 50% of GDP3, and in some OECD countries it goes all the way up to over 100%; in Latin America, there’s a pretty broad range but it’s usually on the 10% to 30% of GDP area. So what the hell are we doing wrong?

Well, if you look at the determinants of the general size of the mortgage market, you obviously have stuff like “how much regulation each country has”, but I think that you need to dig a bit deeper because, for instance, Argentina used to have a much bigger mortgage credit system back in the 1990s, and regulation hasn’t changed that much to shrink it by 95% or whatever. A good way to think about mortgage credit is in two steps: first, the existence of credit in general, and second, the allocation of these funds to housing credit. If you look at general data on credit as a share of GDP, you find that Argentina’s financial sector is unusually small, with much lower loans/GDP or numbers of borrowers than most other countries with similar development indicators.

But why does Argentina have such a small financial sector? Unsurprisingly, it’s the “having a very fucked up economy” of it all. Very high inflation is also very persistent and very volatile, which means that it’s really hard to forecast real or nominal variables beyond “the rest of the year”, and it also means that conducting monetary policy, and thus setting and providing guidance on interest rates, is very hard because the relationship between inflation and monetary variables is very, well, variable. Basically, to provide any sort of credit to anyone, you need to have a clear signal of what the rate of return is going to be, which depends on the real interest rate. In the past (and present), the massive uncertainty over real rates of return for financial assets, but also loans, has resulted in savings being directed at US dollars. Volatile economic conditions meant that an optimal investment and asset portfolio would have been made up by 100% USD assets in many time periods, and very rarely would a 0% USD portfolio have been advisable. Since the country also has a history of forced expropriation of US dollar assets (including as recently as 2002), this manifests as US dollars in cash being 20 times larger than formal USD bank deposits. This means, put together, that the country’s macroeconomic problems could frequently become financial and banking sector problems, which inhibited credit - particularly considering the low level of trust that people have in the financial sector and the authorities. Both of these issues, around prices and trust, meant that investment was also overfunneled into the real estate sector, which again meant that lending and borrowing opportunities are reduced, which almost certainly bid up prices and also made the baseline financial sector panorama even worse due to a lack of a supply of loanable funds. This gets into other considerations for the financial sector, like the reliability of the government, as well as issues like contract enforcement and litigation costs.

The second step is that, once you have a financial sector, you develop it towards housing credit. This, again, has some issues in Argentina regarding macroeconomics - mortgages are definitionally supposed to be very long, and predicting inflation and interest rate dynamics over very long times is, well, not easy here. But there’s also more bread and butter “emerging market issues” around the lack of a centralized database of borrowers and lenders with their payment history and information, a lack of up-to-date catastres with updated market values for each property, and legal issues surrounding the fact that it’s hard to secure collateral from borrowers without lengthy judicial procedures. This is especially severe when economic informality enters the picture: many people could have sufficient income to buy a home, but would have a significant part of their earnings not be registered, which makes providing proof of their ability to pay impossible. Additionally, inflation means that older records (especially for property values) are just not very useful, and again the large informal economy, especially outside of major urban centers, means that a lot of property is untitled and thus cannot be used as collateral for loans. There’s also another set of issues, which is that the banking sector can be very concentrated outside of major cities due to the low number of lenders with connections or expertise, which means that outside of those markets you take very high risks in lending for properties - if smaller and medium sized cities face idiosyncratic economic downturns, they can rapidly sink the banks that serve those regions.

The lack of housing credit means that you need to make a lot of money to get any sort of loan: the average household needs to make seven times their income to afford a loan, and rent costs 16% of what a down payment costs, which means that housing credit is effectively off the table. Beyond that, it also results in households needing to take a bunch of risks to buy a home - risks with the exchange rate, risks with conducting all-cash or part-cash transactions, risks around legal issues and titling, risks around borrowing informally from family members. This is not a good way to conduct transactions. So what could be done here?

The argenbundance agenda

What is the government even doing here? Let’s go in reverse order and start with credit. Number one, there’s the fact that macroeconomic conditions are improving (I have my doubts about the sustainability of the program, but the situation is better than in 2023). While an orderly macroeconomic environment is a necessary condition for housing to become more affordable, it’s not a sufficient condition: as mentioned above, other factors, which are both structural and microeconomic, are important ensuring a supply of mortgage credit. Besides obvious things like “reduce economic informality” or “develop a centralized register of debt information” and “develop a centralized catastre of property deeds and give everyone property titles”, there is some mortgage-specific action left on the table.

The first is re-expanding inflation adjusted mortgages, which managed to improve access to loans: the ratio between initial payments and average wages fell from around 5 in the 2014-2015 period to just under 2 in 2016-18, and the scheme only fell apart because of a rapid increase in inflation that badly harmed real wages, as well as posterior government policies that froze payments alongside rents and thus discouraged making higher-risk loans to “lower income” borrowers. Additionally, authorities could also take policies that have worked in developed or developing countries and promote access to the mortgage markets, including for instance by securing down payment assistance for low income borrowers, or providing insurance for informal sector borrowers that they pay back over time.

A second set of policies is to design schemes for incremental housing, also known as self construction, which is a pretty common way to purchase a home: buy a lot, build on it over time. Incremental housing actually represents around 40% to 60% of housing in Latin America, and helps make up for the lack of options for middle income households - it’s possible to purchase a lot and it’s much cheaper than a full home. A compounding issue, that incremental housing solves, is that the fact that credit is available only for high income borrowers means that a lot of big, new developments are also tailored for high income buyers, resulting in very limited “filtering” of housing units and very limited purchase options4. This is especially important for informal land use, since many of these lots are purchased without a deed and they don’t have public services. Ensuring a higher supply of titled and serviced lots (which in the Buenos Aires metro area is an issue) requires a lot of policy changes that I’ve gone over on a previous post about informal settlements, aka “slums”. But in addition, government policy can actually develop loan instruments for incremental housing in particular, such as promoting microloans (the low income population is a pretty big market, though not as big as in other, poorer countries), and especially for loan instruments for materials purchases and services hookups.

But there’s also the much more obvious problem of housing affordability per se and how to reduce housing costs. What has the government done on this end? Well, not much. The first thing to note is that Argentina, like most Latin American countries, has a really big and growing housing shortage, in the millions of units, but not as much focusing on quantitative shortages but rather in insufficient housing quality. Government policy has actually focused on increasing the supply of housing, but not by shaping and directing the market - rather, by directly building new units and handing them over to individual households. The traditional social housing programs (the National Housing Fund, or FONAVI, and the Federal Housing Plans) are characterized by extremely inefficient use of resources, funding (which is provided by the national government and then spent by provincial authorities) being frequently diverted into general revenues, and low rates of completion of projects. Put together, social housing projects have, generally, not been cost effective and largely driven by “politics” - building new projects to show off during election season, with persistently low rates of eviction for nonpayment. Some newer programs, like the Argentinian Bicentennial Credit Program For Single Family Homes or ProCreAr (that is not a very good acronym, yeah) have largely focused on selling state-built homes to middle income households, and while the program has been more effectively managed, it faced another issue: in order to locate the projects in cost-effective locations, they were in many cases built out in remote locations without sufficient transportation services or amenities; otherwise, costs ballooned and resulted in underdelivery due to land prices being bid up by the national government. And it’s worth noting that social housing programs have gotten “the chainsaw” in recent years, with a basically 100% real cut in housing investment in 2024 - particularly with the (illegal and currently tied up in court) dissolution of the Sociourban Integration Fund that is supposed to tackle settlement improvement (incredibly confusingly, the tax that is supposed to fund its operations expired in 2024 anyways so it’s not like it’s saving any money anyways).

Before moving on, an alternative that isn’t being explored enough is, rather than social developments, to start building social rentals: given high rates of rentals in the region, especially for younger households, and would help get around the low effective demand for housing in the region. Thus, focusing on the rental market could be more cost-effective than focusing on homeowners, especially because of (as mentioned literally two paragraphs above) high rates of self-construction. One first option is rental assistance, which was implemented with the Chao Suegra (“Goodbye Mother-in-Law”) program in 2013: it didn’t have perfect results, in large part due to other, deeper socioeconomic issues and some program design complications, but it did improve affordability outcomes as narrowly measured. Another option is building or acquiring housing units to turn them into state-owned rentals: this is a relatively common option in European cities (such as Berlin’s Deutsche Wohnen, and has been implemented in Barcelona and Montevideo), and given that Buenos Aires has relatively high rates of vacant housing, and that many parts of the city and metro area have abandoned or empty lots, it would be an option worth looking into; it was an item on the agenda before the 2023 election, and rental assistance and social rentals were shaping up to be a policy tool with some bipartisan (out of three) consensus.

This gets to the big issue in Argentinian housing policy: land use policy is, well, a disaster. The government, firstly, is very bad the government at managing and coordinating different aspects of urban policy in the Buenos Aires metro due to extremely high fragmentation between jurisdictions, very limited coordination between policy areas in each jurisdiction, and low rates of investment in basic services and infrastructure due to big gaps in financial and institutional capabilities. This is also translated into, for example, a lack of overlap between areas zoned for higher density and transit corridors, or different densities on either side of the City of Buenos Aires boundaries or between municipalities. Land use policy outside the city proper is very strict, with very large minimum lot sizes and low floor-to-area ratios as well as tight limits on density; the City itself changed its zoning code recently to permit more housing in transit-adjacent areas.

There’s also a pretty persistent, and bad, pattern in urban growth: without adequate land use policies, most growth between 2001 and 2022 (the last census) has been via urban sprawl, by expanding the physical surface of the Buenos Aires metro area. In particular, population has grown the most in the outer-ring suburbs of Buenos Aires, but without sufficient services, amenities, or infrastructure to accommodate the growing demand in this outer commuter areas. In particular, transportation infrastructure is really bad, and traffic jams in major highways have become a live issue, in large part because nobody was able to coordinate development between further away municipalities, the national government, and the City on how to accommodate a growing population.

Conclusion

So, what do I actually make of the housing situation? Well, repealing rent control measures was okay but it didn’t actually solve the deeper picture of housing unaffordability, which is caused by structural barriers to mortgage credit developing, a lack of interest in housing policy manifesting itself in very uncreative and “election-centric” housing programs, and very bad and uncoordinated land use in the metro area. So the solution is, uh, build more mixed-use transportation-adjacent housing and also more subway lines. Which is kind of the opposite of what the government is going for, with its opposition to basically any government involvement in anything.

Speaking of, he recently tried to defuse allegations that he had abandoned his five cloned dogs, each of whom are 220 pounds, by showing one of them off in an appearance on a streaming channel. The video was horrendously awkward, with Milei seeming unfamiliar with the dog and being, at times, visibly scared of him. I think they’re just in the kennels at the president’s residence and he doesn’t want to show them off, for what it’s worth.

I’ll note that rates of household formation for this age group crashed in the post-pandemic period due to extremely high housing cost burdens and poor job opportunities, and that the idea of having “roommates” who weren’t a romantic partner or a relative became more common after being relatively novel in years prior.

For whatever reason it’s really difficult to find this figure but the Fed says it’s around three quarters of total household debt, and total household debt is around 72% of GDP. So go yell at them if I got it wrong because I’m not doing more math here.

A pretty common new way of buying a home is “pit” financing, where you make a down payment ahead of construction starting and then continue paying off a “mortgage” while the development takes place. It helps ensure a steady stream of financing for the developer and allows for some consumption smoothing for households, but also has the obvious issue where you don’t live in the apartment you’re buying. And it also only works for multifamily housing, which means appeal is limited outside of major cities and, again, there’s low effective demand for these developments among the lower middle class due to zoning.

Thanks for writing this! Very interesting. I wrote the original viral tweet — when I did, it pretty quickly became clear that the few sentences on Wikipedia had missed some important nuance.

>However, I think that claims that rent “fell 40%” are (while, yes, in a literal sense factually correct) exaggerated and a bit dishonest

Same story with the poverty rate. Yeah it technically went from 54 to 35%, but that was a momentary bleep caused by the record inflation Massa left us with and the delay in salaries catching up, not due to a meaningful change in the living conditions of 10% of Argentines.

However it's still true that Milei's stabilization policies have brought poverty down to the mid 2010s levels and that's worth celebrating.