Drivin' out into the sun

Let the ultraviolet cover me up

Went looking for a creation myth

Ended up with a pair of cracked lipsPhoebe Bridgers, “I Know The End”

Edit: a previous version posted came out well in the email, but wasn’t showing up complete in the web version or the app version, so I took it off until I fixed it.

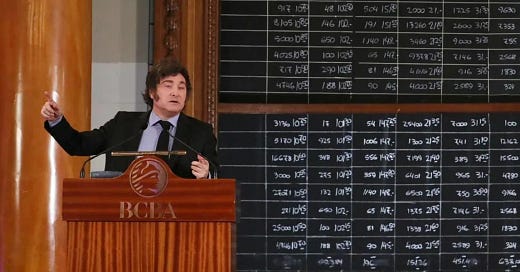

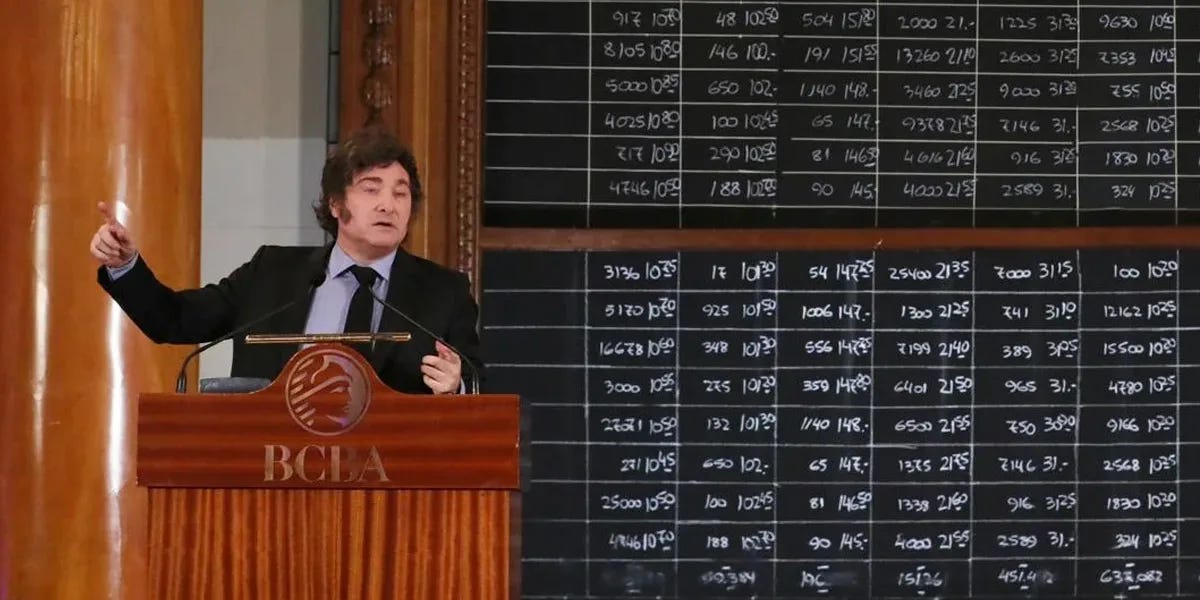

Another quarter, another banger: El Peluca has had quite the first third of the year, with a controversy over his weird homophobic rant at Davos in January, a scandal over his hustling for cryptocurrency scammers in February, massive protests over pensions that resulted in the stuff of PR nightmares, “beat up old people” in March, and a full month and a half of terrible financial indicators in April. The big news, however, is that Argentina and the IMF have finally reached a new deal: the Fund will pony up US 20 billion, and Argentina will do something in return. This is what the government, with plenty of fanfare, has called Phase 3 of its economic program. So now what?

Baby you’re a vampire / You want blood and I promised

What, exactly, is the IMF-Argentina agreement? Well, the Fund will give Argentina 20 billion more dollars, and will hold off on payments that were scheduled for a little while. They also provide some confidence in Milei, since a deal with the Fund is a big deal for local commentators and for the business community.

The big question is what Milei offered to give to the Fund in return - especially because the IMF is paying out 60% of the total amount, or USD 12 Bn, up front (in fact, they already paid him as of April 15th), an unprecedented share since IMF upfront payments are on the 10-30% range in roughly three quarters of cases. On the fiscal front, the proverbial pound of flesh is secure: the government wrapped up 2024 with a 1.7% primary surplus and a 0.3% surplus after accounting for interest1.

The government’s major commitment came in the form of currency market actions: particularly, a devaluation of the peso. It was originally reported that the deal was to not devalue until after the October midterms2 and in return the Fund would put conditions on how to spend the money, but the deal very publicly fell through, so instead my guess was that a deal with a devaluation came through as a second option. So it’s not all that bad, and it managed to calm a pretty dicey financial situation where, over a month and a half, country risk climbed up from ~500 basis points to nearly a thousand, dollar futures spiked from 2% a month to 5% in Q2-25, the gap between the official and parallel exchange rates went from 10% to 25%, and the Central Bank went from recording its best four months in a row since basically forever (excepting last year) to having its worst weeks since the financial meltdown of 2018/19. A lot of it was Trump induced uncertainty, but the rumors of a major devaluation weren’t helping, and at least the government voided the true nightmare scenario, where Trump pulled out of the IMF in June and Argentina was left hanging after it’d secured a deal (because the US is the largest financial contributor to the Fund and free money to Argentina is their largest expense).

The Fund’s major asks were on the monetary front: first, the government let the exchange rate float within the 1,000 to 1,400 range (which is called “a bands system”), with the lower band falling 1% a month and the top band increasing 1% a month. It went to the 1,250 range and then dropped below the value it had before the devaluation even (so long for that), but it hasn’t been that long so nobody really knows yet. Second, the government lifted a bunch of capital controls: most important ones were letting regular people buy a lot of USD in the official market, removing cross-market regulations, some loosening of regulations for private companies, and getting rid of preferential exchange rates for exports. Third, the government shifted its monetary target from 0% monetary base growth to 0% M2 growth3, which results in a less strict monetary target.

So is this good? Well the main risk is basically political: Milei hasn’t been doing too well, since his approval ratings and confidence in government have taken a few hits since the start of the year, especially with a very slow economic recovery and three back-to-back inflation prints that came in above expectations. A devaluation would stoke price growth for a few months, and basically if people consider that the government’s plan isn’t credible, the entire >20% depreciation is going to get passed through to consumers, which would also substantially damage Milei in the midterms. The cardinal rule in politics is el que devalúa pierde (if you devalue, you lose), and I wouldn’t expect Milei to be an exception barring extraordinary circumstances.

However, I also have to say that my main worry was all along that the government wouldn’t pull off the post-devaluation transition where they would 1) have to devalue at the optimal moment (which was clearly either December 2024 or January 2026, but not now), 2) settle on a correct exchange regime for after the devaluation (I think bands is as good as it gets), 3) determine capital controls, and 4) come up with a credible nominal anchor. So is this going to work?

I’m gonna kill you / If you don’t beat me to it

The question “is this going to work” has, broadly speaking, two parts. The first is whether the new exchange rate scheme is going to work. The second is whether the monetary scheme is going to work. Let’s start with the latter.

The main factor to answer these two questions is a seemingly obscure and extremely vague detail: the Fund is asking Argentina to put together 9.0 billion dollars by the end of th year, and here’s the catch, without borrowing them from the repo markets or from other big multilateral lenders (who have already put forward 6.5 billion combined this year). Barring a big bond issuance, which would be a nightmare, or leasing the country to Mister Beast, the only real way that the government is going to get 9 billion in 9 months is by buying them in the open market. This is a problem because the government also promised, as part of the black and white of the bands system, not to buy dollars unless the exchange rate fell below the lowest band - and that value is going to fall continuously until the end of the year. But the Central Bank also somewhat intriguingly reserved itself the right to intervene within the bands, except Milei tweeted that they wouldn’t intervene within the bands, so the other alternative everyone is discussing is the Treasury buying the dollars somehow.

The main implication from having an open ended commitment to purchasing 9 billion dollars in some capacity or another is that you end up needing to print 9 billion dollars in pesos: assuming an average exchange rate of 1,200 until the end of the year, it would add around 11 trillion pesos - compared to a monetary base of 30 trillion in March, and a (private) M2 of 56 trillion. Normally, this would be “sterilized” (i.e. the central bank would pump 11 trillion out of the economy), but part of the announcement was that they wouldn’t necessarily do it. In addition, the IMF lets the government increase the money supply by another 10 trillion (without contemplating the ones for FX purchases), so put together it would be an increase of 37% of the money supply in the remainder of the year - would this cause higher inflation?

Let’s look at the Quantity Theory of Money: the change in the money supply has to equal the change in velocity, the change in GDP, and the change in inflation. GDP should grow around 5% in 2025, so you only really have to account for around 15% in money growth - the question is whether velocity drops enough to cancel out price growth or not. Velocity (the amount of time each unit of money changes hands i.e. how quickly people spend money) is the part of the equation where “vibes” are in, so if the government’s plan is credible, velocity drops, the real demand for pesos increases, and the numbers work out. And if there’s no credibility, it increases, raising inflation and passing through the devaluation. But that means that the question “is the government’s plan credible” only has one answer, “if the government’s plan is credible”. Not very fun. I think there’s a pretty fundamental way through this, and it runs through what is allegedly Milei’s strongest area: fiscal policy.

The 1.6% of GDP target for a fiscal surplus is feasible, but it’s above the line, and meanwhile the government’s debt is growing below the line - basically, this is a tricky distinction that mostly relies on methodology, but the government’s new monetary policy involves all central bank operations running through the Treasury (through a bond called LeFi) as a way to prevent them from printing money to finance the deficit. Additionally, the country’s best bet at getting the 9 billion pounds of flesh the IMF is asking for is to just borrow them - either straightforwardly via bond sales, or more covertly as some weird USD-denominated buyback operation. But either way, the country borrowing more is the easiest bet, and the government’s commitment to 0% deficits means that it’s a safe enough bet, right?

Well, no. Going all the way back to the name of this blog, there’s a limit to how much anyone will loan to a country. Imagine a country that is running a deficit and funds it by printing money; if it stops, it can borrow in return, in exchange for tighter monetary policy (because it prints less money). The problem is that, if the deficit remains stable, then eventually you just run out of borrowers, so you have to go back to printing and in fact have to print even more, because you can’t even borrow anymore (this has a lot of complicated dynamics behind it). This is called the unpleasant monetarist arithmetic and basically the point is that you cannot run a deficit with tight money and expect inflation to go down if it’s possible to monetize it - in fact the whole reason why the last macro stabilization effort didn’t work was (besides some technical glitches with inflation targeting), that the government ran out of money to borrow and was running a pretty big fiscal deficit - particularly considering that a lot of the debt was in dollars (called “hard money debt”) and therefore the simultaneously occurring currency crisis ballooned debt payments4.

But Milei isn’t running a deficit, right? Well, he’s not running an above the line deficit, but he is having debt grow, and he is running a below the line deficit5. At the same time, he’s also pumping enormous amounts of liquidity into the economy as a way to purchase unsterilized dollars, which adds a big dose of uncertainty. So the unpleasant arithmetic does play a role: either throught the whole LeFi mechanism or through the dollar debt mechanism or through something more exotic involving hard money debt. This is also all especially noteworthy because the amount of money that a country as unreliable as Argentina can borrow depends a lot on global apetite for risk, and the global risk premium right now is incredibly high because of Trump’s shenanigans, so the hard money below the line debt strategy might end up backfiring horrendously.

Windows down, scream along / To some America First rap, country song

This whole thing ended up coming down to the usual: is the government going to pull off the exchange rate switcheroo? To answer a complicated question, we need to go back to basics. Accumulating reserves (that is, the 9 billion target) depends on the balance of payments - that is, the amount of money entering an economy. Under a fixed exchange rate, supply of hard currency exceeding demand means reserve growth and viceversa, while under a floating rate reserves are held constant and the exchange rate responds to market forces. If you want stability, you have to go with a peg (most stabilization programs use pegged exchange rates as anchors), and if you want reserves, you go with a float. The bands system is sort of an intermediary that lets you still manage the exchange rate with reserves, but you need way fewer of them, which is good because Argentina does not have a lot in terms of reserves.

The main determinants of the balance of payments are the current account and the financial account, as well as a capital account that we’ll ignore because it includes IMF payments (already accounted for) and a bunch of weird stuff that doesn’t really come up most of the time. The current account has the trade deficit (or, in Argentina’s case, a modest trade surplus), the services trade deficit, a bunch of stuff like wages and interest payments, and remittances. The financial account has foreign investment - FDI as well as “porfolio investment” (buying financial assets), as well as loans to the government and private sector. Argentina’s strategy for accumulating reserves was, in 2024, to restrict the financial account using capital controls (basically regulations on foreign investment), and to let dollars get into the country via a current account balance - particularly, a large trade surplus of 19 billion USD, since exports went up thanks to the weak exchange rate, and imports went down due to the recession. However, the trade surplus is expected to shrink by over 10 billion, and the stronger currency means a much bigger services deficit (for example, March and February had the two highest tourism deficits in 20 years).

With that in mind, the government’s idea makes sense: the math didn’t pencil out for a current account based strategy to meet IMF targets, so they loosened the financial account to, well obviously borrow money in global capital markets again, but also attract foreign investment and make up the difference (as well as boost economic growth via higher investment in general). But the thing to consider is what’s known as Mundell’s Trilemma: the idea that a country can’t simultaneously control the exchange rate, the interest rate, and have an open financial account. This is because capital flows are determined by what’s known as interest parity: the interest rate of country X has to match the global interest rates (US rates) plus the expected currency devaluation plus a risk premium. The intuitive meaning is that if you want to have interest rates lower than the rest of the world, then investors will leave, which means that if you float your exchange rate then you just have to let them leave and devalue your currency (because demand for dollars increases), while countries with a fixed exchange rate either have to give up reserves or ban investors from exiting the country (which would raise the risk premium, in theory). Argentina wanted to control both the exchange rate and the interest rate up until last week, thus the government had to place controls on capital flows. From now on, Milei wants to go to a system where the government controls interest rates, mostly doesn’t control the exchange rate and mostly controls capital flows - which provides enough flexibility to accumulate reserves while also not needing as many.

The main problem is that it might not be a trilemma at all - just a dilemma, between monetary sovereignty and free capital flows. Basically, a major problem is that the global financial cycle does not seem correlated to basically any individual national economies: even in countries with low and stable inflation and with deep domestic financial markets, there are substantial aftershocks from Fed policy shifts. This means that even countries that should be well-insulated from global financial instability have to respond to it - and since it’s not really possible to coordinate global monetary policy to a large extent, then if countries don’t want to restrict their own financial systems (which hurts growth), or have fixed exchange rates (which would waste their reserves), then they need to impose moderate capital controls because otherwise global financial movements will force their hand in suboptimal ways. The obvious thing going on right now is that the global financial market is, to put it in technical terms, fucked: the dollar is sharply depreciating, Treasury bond yields are spiking, and the US stock market is having its worst year since 1929. The weaker dollar means pressure on currencies, and combined bond and stock market movements imply a flight to safety, that is a higher risk premium - so global interest and exchange rates are trending upward. Given that higher interest rates would depress output, and that higher exchange rates could be inflationary (and also depress output), then the alternative to just tighten the leash on foreign capital flows a little bit may seem more appealing since it doesn’t have the same implications for macroeconomic variables.

So, overall, I think that the capital flow deregulation is pretty by-the-book: Milei isn’t letting the financial markets run wild, but rather, just ensuring that financial flows are smoother between the official and parallel markets, which should stabilize the exchange rate somewhat. The interesting part is that I think that the government is still angling for the currency competition framework, which does need some form of capital controls to keep US dollars in the financial system while most operations are conducted in local currency. Consequently, it appears that the govenrment’s partial loosening of some capital controls is conducive to currency market stabilization, as long as capital controls aren’t excessively loosened over time. An item of note here is that the government sneakily authorized domestic transactions with USD-based debit cards in January, and additionally lifted some macroprudential regulations on hard currency credit - the idea here is to normalize USD-based operations in the domestic economy, which would need a market-based exchange rate to actually be used. This begs the question, if the authorities actually want to firm up the legal footing of the peso and the dollar, are they actually building on top of solid currency foundations, or on top of quicksand?

No longer a danger to herself or others

I do think that a problem is that, even though the market value of the exchange rate can be low (in real terms) and stable, it is still not necessarily an equilibrium value for the balance of payments - particularly because demand and supply of pesos and dollars is determined by broader variables such as macroeconomic credibility and exchange rate expectations. In particular, if inflation expectations are low because it’s expected that the government would stamp out a devaluation, then the market price is not actually an equilibrium price - because managed exchange rates tend to be overvalued, while monetary stabilizations tend to intervene excessively.

The main reason cited for this is what’s called the “fear of floating”: the consistent and persistent reluctance of central banks to let the exchange rates float. This is particularly noteworthy since very few countries that claim to float their currency actually do, and most just kinda float it in some contexts. Most explanations for the fear of floating come from output costs, where currency depreciations are contractionary; I think that, as mentioned above, the reason for Argentina in particular is that policymakers are scared that it would raise inflation, the loss of credibility for the central bank even without any actual impacts, and in some cases, that it would affect financial stability due to a high share of dollarized loans and contracts.

So this means that the currency should be stable within the bands (because expectations are that it will be kept in check), even if it’s not necessarily true that the market value of the exchange rate is “correct”. This gets to some fairly convoluted currency economics issues, but at its core, it’s a similar story to a fixed exchange rate: fixed rates plus an expansionary monetary policy mean that, at some point, the total monetary supply divided by the exchange rate equals the total reserve stock. In this case, “speculators” swoop in and buy out the reserve stock, forcing a devaluation. This can actually happen to banks that do have enough reserves to defend their pegs, in large part because large-scale reserve selloffs imply very contractionary monetary policy (they are quite literally sucking billions out of the economy), and central banks don’t always want to provoke a recession.

In fact, an extremely common story in 1990s Latin America was that countries would fix the exchange rate in order to reduce inflation, which would over time lead to overly strengthened currencies, which drains their international reserves slowly over time - and, with an open financial account, results in a private sector that is not just overly indebted, but overly indebted in a hard currency. Normally a mix of credibility and good vibes would keep the ball rolling (the Mexican peso was kept on life support by NAFTA even after it was self evidently too strong by the early 1990s), but eventually people just stop trusting that the house of cards is going to hold. The first option is that everyone just gets the heebee jeebees and pulls out - which is called a sudden stop and is what happened to Argentina in 2018, when it had a floating exchange rate and 45 billion in reserves to control it. The other option, which is what happened to all the other Latin American countries in the 1990s, is contagion: basically, once someone goes down, everyone else starts being worried regardless of how tangential a connection they have, and suddenly the crisis spreads across markets.

So could either of these happen in Argentina? Well, kinda. The first part, a sudden stop, we’ve already been over both in this post (the whole dedollarization debacle) and also in the past - it’s quite literally what happened in 2018, when everyone got cold feet on emerging markets in the middle of Trump’s trade war with China. Another similar and recent event, given Milei’s social circle as well as the whole “idiot market hypothesis” post truth thing, is the Silicon Valley Bank scenario: stupid venture capitalists just shitpost each other into tanking the country’s financial system. The second part is even more obvious: Trump tanking the global economy with tariffs is not likely to attract investment. I also want to bring up a third path, which is that the system just unravels on its own, and this is largely going to be up to politics and broader expectations/narrative things: back in 2019, when the currency bands were first implemented, they worked until exactly August 8th, 2019: the government was forced to abandon them basically overnight on Monday after a 16-point election loss following 6 months of tied polling averages. The unpredictability of both global and domestic policies means that the “black swan” scenario… is pretty plausible.

The big, final, million dollar question is that, if either Trump or something else breaks the country’s currency, what would be the consequences. Well, as I’ve mentioned, both higher inflation and a recession, which would be bad. But Milei’s moves to loosen capital controls and financial regulations and integrate the dollar into the economy could mean an even worse, more destructive outcome: a financial crisis, where a central bank hamstrung by the whole LeFi system and the currency bands and interest parity and the tri/dilemma has to rescue the banks. Back in the 1990s, when the country had a 1-to-1 exchange rate fixed by law and the dollar was legal tender, currency depreciation was avoided like the plague because everyone understood that the economy would completely unravel; except, when it became inevitable to devalue by 1995, the economy entered an extraordinarily prolonged slump basically as a way to preserve the parity through contractionary monetary and fiscal policy (to stop the bleeding via capital inflows and less governent debt). Then the economy more or less completely collapsed anyways because the government was forced to abandon the parity basically overnight and dissolve all existing contracts and shut down a bunch of financial institutions.

Conclusion

I don’t actually think that the economy is going to collapse, though, mainly because I don’t think that if something breaks it’s going to take ten years. I think that loosening capital controls in a year where the global economy is juggling with five apples and the hand grenade of tariffs may prove devastatingly stupid mistake, particularly considering that currency market stability is make-or-break for stabilization programs. I think that the risk here is that the currency would be excessively strong, because of expectations that the government will keep it contained, which would both over-dollarize the economy (because of the currency competition framework and the cheap credit) and expose it to speculative attacks or just to investor heebee jeebies down the line. Both of this would be devastating even on a small, 2018/19 tier scale.

On a fundamental level, the program seems sound - “phase 3” works in theory, unlike Milei’s campaign promise of dollarization. But, as I think we all know, we don’t live in the pages of a macroeconomics textbook. We live in a world where an insane old man asked ChatGPT to come up with the tariff rate on an island populated by penguins.

Readers with long memories may be wondering if this includes LeFi payments. It does not.

Readers with long but less detailed memories might be wondering why the country isn’t having primaries this time around and fortunately they got rid of them as part of a broader election reform push that did not include any of the wacky parts from the 2024 draft bill.

It wasn’t technically 0% monetary base growth, it was broad monetary base growth responding to real money demand until it reached the value it had pre-shock therapy per the combined amount of the actual money base plus central bank liabilities.

People who pay a lot of attention will start noticing that if the last blowup happened in 2018/2019, then isn’t this is going to end up being Donald Trump’s fault and yes, it will be.

Incredibly confusingly, the IMF limits what are known as “arrears” (basically debt incurred by the government pushing payments down the line), which is usually the bulk of below-the-line debt, but does not actually directly limit below-the-line debt.

I gave me a lot of joy to see how you built this on Phoebe Bridgers fragments. *Slowclap*

Sounds like the most likely way they were going to pull this off and find the money was to be able to stomach a harder devaluation of the currency now that that solution is off the table you are left with figuring out how to borrow more money on the international market as a high risk borrower, attract foreign investment super fast, or find a way to raise additional revenue (hopefully they don't decide to tax exports again). The crypto shenanigans and stunts with Elon make them seem like the remaining the country that exists to show others what not to do on macro management but this is the best macro management they have had in a while.