What Went Wrong in 2018?

"Stuff happened" - Mauricio Macri, President of Argentina (2015 - 2019)

It would be ironic if all we could conclude from this episode is that Macri’s Achilles heel was, in the end, just old-style populist short-sightedness.

2020 was not a great year for Argentina, with GDP contracting 9.9%, poverty growing, inflation accelerating throughout the year, and unemployment rising. But COVID is not the start of the country’s present troubles - 2018 is (technically, 2007 but still). In 2018 and 2019, inflation rapidly accelerated from 25% to above 50%, amid a rapid devaluation of the peso. GDP shrank roughly 5% between both years, and other economic indicators worsened as well. Just four years before 2019, center-right President Mauricio Macri was elected on the promise of ending inflation and “normalizing the country”, to high local and international hopes. So what happened?

The heavy inheritance

The best way to start is to look at what the government started with. Between 2011 and 2015, the economy had not grown, as inflation steadily accelerated from the 10s to the 20s, 30s, and even occasionally the 40s - not that we know of, because government statistics had been basically fake since 2007. The budget deficit was large (the precise size is disputed because of semantic issues), it was primarily funded through monetary emission, a large chunk of prices were artificially in a fool-headed effort to control inflation (read more on it here), and the currency market was basically centrally planned, with an opaque bureaucracy deciding case-by-case who could buy US dollars (a really big deal in Argentina) and how many. Either way, the real exchange rate had fallen to its lowest levels since 2001, and net international reserves were starting to become negative.

A particularly thorny subject was public utility bills, which had basically not increased in nominal terms for the better part of a decade, resulting in the government paying for 92% of the cost of services - and those transfers explaining 74% of the total deficit (roughly 3% of GDP). Given the realities of access to public services, those subsidies were targeted disproportionately at the rich.

What did the government plan on doing? A gradual adjustment, known coloquially as “gradualism”. It is worth going into some detail on how that was supposed to work. Economically, since debt was relatively low as a fraction of GDP (at least debt with the private sector), a smoother adjustment could be made. But the motivation was primarily political: a “shock” program that cut taxes and axed spending might be politically unsustainable, and even unfeasible, for a government with minorities in both houses of Congress and with just three governorships.

The plan, then, was to cut taxes first, reduce monetary financing of the deficit (the root of all evil, as it were) and replace it with private-sector debt. Reforms to tax, labor, and trade policies would boost growth, and all of those put together was going to slow inflation. Monetary policy played second fiddle here, with somewhat positive real rates to incentivize savings and a floating exchange rate to reduce distortions to the market.

The key to reducing inflation was an inflation targeting regime, where monetary policy aims to accomplish a given rate by a certain date - in this case, 5% by 2019. The peso would be devalued quickly by removing all restrictions immediately, which would not increase inflation because expectations were already using the black market exchange rates as an anchor instead.

The big problem to avoid in inflation targeting (IT) is time inconsistency, i.e. that the Central Bank promises lower inflation but then never actually goes along with it, for any number of reasons. The big risk for IT programs, then, is a loss of credibility, i.e. that the Central Bank simply slacks off and stops reducing inflation halfway through. This is why the absence of fiscal dominance, where the Treasury bosses the Central Bank around into financing spending, is a big precondition for IT to work in the first place. Moreover, no successful IT program can include a nominal anchor (i.e. a fixed exchange rate, basically) since it can bind them in suboptimal directions for overall policy, plus usher in balance of payments crises and/or financial crises, the latter of which had happened in Argentina during the 1990s and which soured everyone on exchange rate-based stabilizations.

Either way, inflation targeting for high inflation is farily controversial, since most countries that successfully applied it had moderate headline rates (i.e. mid teens). In addition, the key issue is that having too low a target and/or too short a time horizon to achieve it can wreck the program, since it is widely known that monetary policy affects the economy with lags of perhaps as long as two years. As a result, IT disinflations for initially high inflations have to be phased in, to account for the delays in the program’s design. And, once again, IT is incompatible with a fixed exchange rate because it can require drastic adjustments to monetary policy to account for, basically, bad luck.

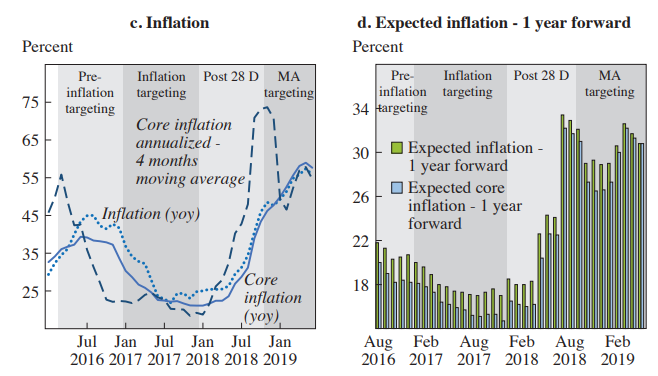

Initially, this program was both economically and politically successful. The tax reductions, paired with basically no change to total spending (as pension and welfare reforms expanded it while axing subsidies reduced it), grew the deficit. As the country had been able to settle its longstanding default, private debt (mainly in US dollars, due to the weakness of the government’s credibility and the threat of seigniorage-fueled inflation eating away at the interest payments) made up the difference. Meanwhile, the inflation targeting regime, despite all the limitations, proved somewhat successful at both anchoring expectations and reducing core inflation. The government rode these to a victory in the 2017 midterm elections.

But pride goeth before destruction, and a haughty spirit before a fall. In December 27th, 2017 (a day before Innocent’s Day, usually characterized by pranks) the authorities announced they were raising their inflation target for 2018, and cutting the monetary policy rate. Exactly why they did this is a bit of a mystery, but it had a negative impact in the government’s credibility (no joke).

The next year, the Federal Reserve tightened monetary policy, and a large drought hit the country, putting increased pressure in the exchange rate. Absent interventions by the Central Bank, the traditional anchor for expectations soared and inflation followed. Two Central Bank Presidents resigned in 2018, and the Treasury Secretary did so too in 2019. The economy entered a recession, and monetary and fiscal policy suddenly tightened as the country entered an agreement with the International Monetary Fund (reaction video for Spanish speakers). The same story unfolded multiple times, as bad news coming from abroad resulted in multiple runs on the peso through 2018 and 2019. By July 2019, the situation had settled, until a sudden landslide victory by the Peronist Party (and its traditionally, let’s say, market unfriendly policies) triggered a full-scale financial crisis.

Achilles’ head, shoulders, knees, and toes

Exactly what went so wrong is up for debate. Sturzenegger (2019), a generally good paper, puts the blame entirely on the Treasury, and praises the performance of Central Bank President… Federico Sturzenegger. Di Tella (2019), in response, points out his mistakes in a less than cordial tone, starting off with “the paper does not explain why Macri and other members of the government failed to appreciate [Sturzenegger’s] progress and fired him”, and describes him as (I paraphrase) “an exogenous enabler of the gradualist approach”. Ouch.

Starting off, regardless of what the Central Bank’s mistakes were, nobody denies fiscal policy was not optimal. Reducing spending gradually, and only after gaining political capital from cutting taxes, is not a particularly credible policy -it’s basically just the government wanting to goose the economy before an election. At the same time, unfavorable Supreme Court rulings and tax cuts resulted in a much higher deficit in 2016 and 2017, plus the fact that the 2017 pension reform involved growing expenditures due to real gains in backwards-adjusted pensions. This required more debt and made problems servicing it, even to the point of returning to seigniorage, a likelier scenario (more on this later), and took away credibility from the plan.

The fiscal front had no significant progress to speak off by 2018, and most of the adjustment efforts came after the recession had already started. His explanation for why monetary policy changed is that the Treasury and Finance Ministers (briefly separated) wanted a slower disinflation and lower interest rates, so they demanded policies be changed, and Sturzenegger (though he doesn’t directly stated) folded and let them have their way - as Di Tella put it “Perhaps Sturzenegger did explain in detail this to the political authorities and they were simply insatiable. In that case, we should revise our view of who are the populists in Argentina”. Not a great look.

Money, money, money

Monetary policy did a good job though… right? Not really. Sturzenegger says that monetary policy was always appropriate, but Di Tella disagrees. The core arguments made by Sturzenegger are pretty simple: inflation targeting was an appropriate tool to stabilize the economy, pegging the exchange rate was too costly, incomes policies were useless, and neither utility hikes nor devaluations were going to be inflationary.

Regarding incomes policies, they are a combination of fiscal correction and wage-price controls, and have a decidedly mixed record. I’ve written before about why I think price controls basically never work; to quote Scott Sumner: “If you don’t have a credible monetary policy, then wage/price controls won’t solve your problem.”. The big examples of “heterodox” stabilization plans like this are the Austral and Cruzado plans from the mid 80s (in Argentina and Brazil respectively), and neither of those actually managed to reduce inflation: Argentina careened down into hyperinflation right after the linked paper was published, for instance. In hindsight, it seems pretty evident that basically all the credibility came from the fiscal adjustments and not from price controls, which were more a token gesture to garner political support. In addition, an exchange rate anchor cannot, as I’ve said a few paragraphs above, work as a compliment to IT, since it would impose too many binding constraints on monetary and fiscal policy, Convertibility-style. A pegged exchange rate could have acted as an initial way to disinflate the economy, but it would have been impossible to maintain with the lowest rate exchange rate in 15 years and negative net international reserves.

Why was inflation targeting such a bad fit, according to Di Tella? For once, it’s not particularly clear how Sturzenegger’s immediate disinflation was supposed to occur, and especially unclear how it was supposed to not have any immediate economic costs. It’s possible to disinflate the economy, perhaps even rapidly, without these costs, but it’s never explicitly laid out how an ultra-aggressive IT regime was supposed to do that. Furthermore, it’s not especially clear why IT was supposed to work at all considering Argentina had a much higher starting inflation rate than any other country where such programs were implemented - and those countries had much less aggressive programs, coupled with more disinflation-friendly fiscal and currency market policies. Di Tella mentions how IT works as a compliment to an initial disinflation, but not as a way to disinflate the economy per se, and other papers (such as De Gregorio, 2019) claim that it is not useful at all for disinflation.

Probably the most questionable assumption at the heart of the whole debacle has to do with the inflationary effects of a devaluation and of utility price adjustments. The ongoing assumption was, explicitly, that neither was inflationary. A devaluation would not be inflationary because everyone already pegged their expectations to the parallel exchange rate; meanwhile, utility hikes would not be inflationary because of the budget constraint simply reducing excess spending in something else. At the household level, both seem reasonable enough, but at the firm level it would be extremely mistaken to assume either. Lastly, the authorities seem to be confused between whether they were supposed to be targeting the headline or core inflation rate, a particularly risky issue when big regulated price adjustments were on the agenda - headline inflation directly incorporates regulated prices, which meant that even on-target inflation would be perceived as above target, simply because there were more prices going up.

Not mentioned by Sturzenegger, the Central Bank’s choice of targets was also questionable. They were exceedingly ambitious, planning a reduction from around 37% in 2016 to just 5% in 2019 - and missed two of them in a row, 2016 and 2017. The Central Bank refused to change its targets in the face of missing them by a mile, since “to change the target is to not have one” (i.e. out of credibility concerns), but constantly missing the target might also deteriorate credibility. Regardless, the 2018 target was revised upwards in the 28th of December (28-D as it was later called) and resulted in… higher inflation expectations (5pp actually) and lower real rates, paired with lower nominal rates.

And then there’s the currency market aspect, ignored by both. The government expanding the deficit in 2016 and 2017 (partly their fault, partly things like Supreme Court rulings) and the need to actually disinflate the economy required to replace financing that was majority monetary emission with financing from the bond market. Because the bond market in local currency was virtually non-existent, and inflation-adjusted bonds would have sent the wrong signals i.e. how much the government believed it could reduce inflation, the only option was bonds to be paid in US dollars. This tied fiscal policy to global economic conditions, but also to domestic ones - making the deficit procyclical, since capital would have fled the country following any bad news. This last episode is what’s known as a sudden stop, a (well) sudden reversal of capital flows into the country, with a number of associated problems. One such event happened in early 2018, partly due to the inconsistencies within government policies and partly due to international factors. Consequently, this raised the issue of needing to rapidly resolve the financing of the deficit (sudden cuts to spending, it turned out). Secondly, this “sudden stop” resulted in unrest in the currency market, and since the Central Bank seemed committed not to anchor the exchange rate, whether or not a devaluation would pass through to prices was a vital question. From the looks of it, it did, although it’s likely this was driven by higher inflation expectations (the US dollar did still work as an anchor of sorts).

Some Unpleasant Arithmetic

The trouble is that monetary and fiscal policy cannot be mismatched like that for any stabilization plan to actually work out. The first reason is pretty simple: inconsistency between monetary and fiscal policy, per se, takes away credibility from the authorities - and credibility is the lifeblood of any stabilization plan. The number one reason plans to reduce inflation, even correct ones, don’t work out is very simple: if inflation comes from faster aggregate demand growth than aggregate supply, that demand has to belong to someone, and that someone won’t want to give it up (defining it based on faster money supply growth than nominal output growth is the same, because someone has to have that money). Politically, if someone has money and doesn’t want to give it up, there’s going to be some political actor sticking up for them.

But this wasn’t a correctly designed plan, either. Remember how the first condition for inflation targeting to work was the absence of fiscal dominance? Well, haha fat chance. Between 2007ish and 2015, the government made a conscious (mainly ideological) choice to replace financing through the debt market with financing through the Central Bank, at the same time as the fiscal accounts went from having a 2% surplus to a 6% deficit. Why is this a problem?

Imagine a government that has a deficit fixed at a certain real amount for the foreseeable future. There’s two ways of financing that: through debt and through inflation. Given that there’s so much money going around in the economy (even with economic growth and whatnot), then the demand for bonds always has an uppermost bound. Given the announced deficits, people will demand fewer and fewer bonds the closer the government is to the bound, for the simple “nobody has money to lend” rule, and the Central Bank steps in to make up the difference.

So imagine the Central Bank only has independence when the demand for bonds is not binding. Then, tighter monetary policy necessarily results in more bonds, which means the bound is reached sooner. Inflation first falls, because of less money being printed, and then increases, so tighter monetary policy can permanently increase inflation in the right circumstances. This is what Sargent & Wallace (1981) refers to as the Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic: under fiscal dominance, inflation is a fiscal phenomenon. And maybe not even that, since any number of reasons (for example, previous experience with this phenomenon) could result in nobody ever buying the tighter policy gambit, meaning that the plan immediately increases inflation.

What is the relevance? Well, it’s pretty easy to see. Unless you break fiscal dominance, then Sturzenegger’s tight monetary policy was just pushing the demand for government bonds to its breaking point. If you add into that the larger deficit and the issues involving that monetary policy got looser for no apparent reason, you might just get a sudden downwards movement in the demand for bonds, and ergo the unpleasant arithmetic hitting sooner.

Conclusion

So in the end, the downfall of the Macri administration was twofold. Firstly, they started off with the wrong impression of what they were supposed to be doing: inflation targeting and mainly lightly brushing off fiscal accounts, with not much thought given to currency market issues or the demand for bonds. Secondly, even the wrongheaded things they planned on doing could have worked out with some luck, but they implemented them so poorly they were doomed to fail - the bizarre 28D press conference the main offender of them all. Any future serious attempt at macro stabilization has to start by breaking up the fiscal dominance hamster wheel to ever have a prayer of succeeding.

A talking point I didn’t touch upon before, but will do now, is that the problems were caused by prioritizing “microeconomic orthodoxy” over macroeconomic stability. Outside of the realm of taxes, this is just hogwash. On the supply side, the Argentinian economy is crippled by special carveouts given to whichever lobbyists can get the government on the phone, so any attempt at dislodging them from profiting off the consumer are net good - I don’t really see how deregulating air traffic, opening up trade for electronics, or reppealing ridiculous regulations put macroeconomic stability at risk. The main problematic ones are export taxes, but it’s fairly obvious that the risks of a devaluation blowing up inflation expectations (which actually did happen) are/were greater than the risks of perhaps causing issues related to more seigniorage.

Sources

Manuel Alcalá Kovalski, “Lessons learned from the Argentine economy under Macri”, Brookings, 2019

Sturzenegger (2019), “Macri’s macro: The meandering road to stability and growth”

Di Tella (2019), “Comments on Macri's Macro by Federico Sturzenegger”

The past

Inflation stabilization

Bernanke & Mishkin (1997), “Inflation Targeting: A New Framework for Monetary Policy?”

De Gregorio (2019), “Inflation Targets in Latin America”

Sargent (1981), “Stopping Moderate Inflations: The Methods of Poincaré and Thatcher”

The Unpleasant Arithmetic

Sargent & Wallace (1981), “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic”

Bruno & Fischer (1987), “Seigniorage, Operating Rules and the High Inflation Trap”

Great work as always: entertaining, witty and reflective on the past and extract some lessons for the future.