I haven’t been very active online this last two weeks, which was because I was busy with a new project for my master’s program: with some students from the University of Southern California (you know, the one Jacob Elordi’s girlfriend’s mom went to prison over), we sat down with experts and government officials, read a bunch of papers, and ultimately put together a video and some personal policy work on informal settlements in Buenos Aires (my hometown). Since it’s an interesting question to me (and one I was circling around doing before the project, even), then here we go: where, exactly, do “slums” in the developing world come from?

What we don’t imagine we can design

The first thing to understand here is that “informal settlements” (the polite, academic term for slums) are not really something you see in the developed world, and something you see everywhere in the developing world. Just over half of the world’s 8-billion strong population lives in cities, and 1.6 billion (or a fifth) lives in informal settlements, with that number to increase to 3 billion by 2030. Basically 0 of them live in developed countries, outside of tent cities by the homeless and extremely marginal immigrant communities.

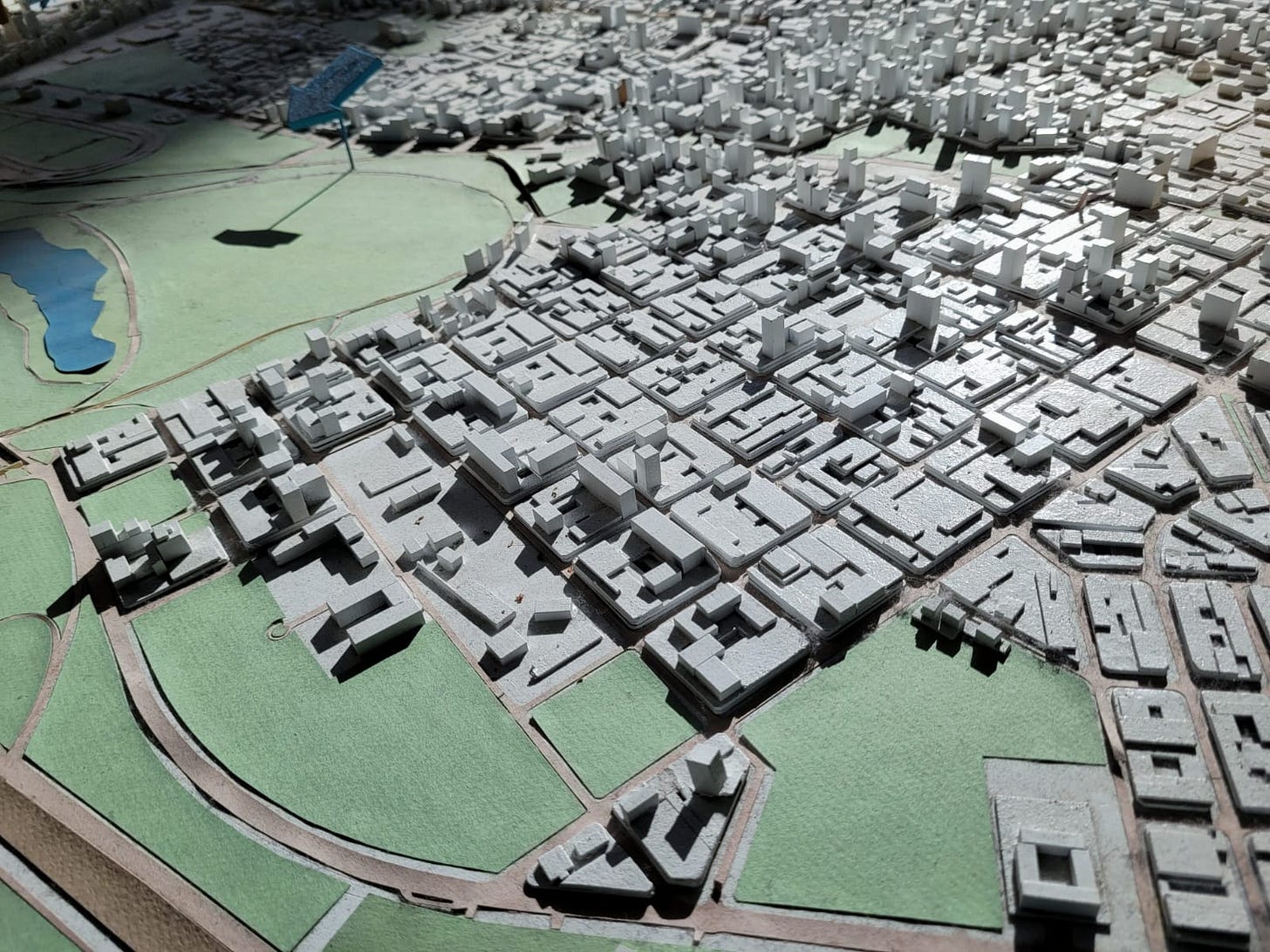

In Argentina1, there’s 1.2 million families (or roughly 4-5 million people - around 10% of the country’s population) in informal settlements, and 500,000 and change live in the Buenos Aires metro area (so 42% - in line with the 38% of the population that lives here). The metro area is inhabited by around 16.5 million people, of which 3 million live in the City of Buenos Aires proper and 14.5 million in the metro area (called the Conurbano), compared to 3 million and 3 million each in 1960. To get an extremely confusing part of it out of the way, the Buenos Aires metro area is the City of Buenos Aires, which is an independent province of Argentina, and 39 municipalities in the Province of Buenos Aires, which is separate. It’s like Washington DC and Washington State, except Washington was the name of the state of Maryland. And even more confusingly, the provincial capital of Buenos Aires (La Plata) is also part of the Buenos Aires metro area.

There’s around 1,500 informal settlements, most of which were built after the 1980s, and they are not nice places to live. A majority of households live in precarious or very precarious housing: 98% of settlements are not connected to sewage, 92% do not have running water, and 69% do not have electricity; plus 42% of settlements are in areas with environmental hazards, particularly related to flooding (from severely polluted rivers) and landfills. 81% of residents have insecure forms of tenure, and, despite the low quality of housing, pay rents 16% higher than comparable ones in the formal sector, and land prices are 140% higher. The population of these settlements has unemployment rates exceeding 20% (versus a national average in the 7% range in the post-pandemic period), around 20% of youth are neither working nor studying, and unpaid forms of employment represent between a tenth and a fifth of employment.

So it’s a really big problem. Traditionally, the solution to this type of urbanization is to just force them out - back in the time of Robert Moses, he would simply tear down their homes and make them go live somewhere else, which is a generally bad idea (for once, where else would they go but other slums). Back in the 1990s, the national government wanted to empty out the Villa 31 (currently known by the more euphemistic “Barrio Padre Mugica”) by buying them all out for 10,000 dollars, but the Catholic Church, led by the then-Cardinal Jorge Bergoglio, united all opponents of the idea, and it kinda fizzled out. So instead, policy has mostly focused on improving the quality of life for settlement dwellers, either by moving them to social housing or by improving quality of life, which has very hard to prove economic benefits (in large part because it doesn’t seem that they do much except make the properties more valuable), and very hard to estimate costs.

For example, the Mexican government says that it would cost 830 dollars per family per year for three years to end informality. Let’s double that just for precaution, and it adds up to 1.3 billion dollars. Given Argentina’s GDP of 600ish billion, that’s 0.2%. The government earmarked funding for settlement upgrading in the Sociourban Integration Fund (or FISU), which Milei shut down last year;since it had a budget of 0.3% of GDP, it would be over in a year of serious investment. Another estimate of this is the PROMEBA (Programa de Mejoramiento de Barrios or Neighborhood Improvement Program), which provides basic services and property deeds to informal settlements. Using some rough napkin math2, it would cost around 3.5% of Argentina’s 2024 GDP to apply the program to all settlements in the country, which means that it would take 10 years of investing a feasible sum to solve the issue. However, if you take the example of one of the most impressive cases (Barrio Playón de Chacarita), which cost around 700,000 dollars per household, it would take 385 billion dollars to turn all settlements into regular neighborhoods, or nearly two thirds of Argentina’s GDP; which means that investing the FISU sum, it would take roughly two hundred years to end residential informality in the country.

But the obvious issue is that these settlements didn’t just appear out of thin air. People have kept moving into them for the better part of 50 years. So if everyone in them had deeds and electricity and whatnot (and the ones that were in like, polluted floodplains moved somewhere else) it would give you no guarantees that nobody else would move to settlements after that - particularly because there’s some evidence that upgrading programs do, in fact, promote further settlement construction. So you need to look at not just what to do about settlements, but why they exist - so you can act on those root causes. This is especially important given the fact that it costs around six times more to hook up an informal settlement lot to public services than it does for a lot that hasn’t been urbanized yet.

Not In My Black Market

In the City of Buenos Aires, it costs around 70% of a young person’s wages to rent a one-room apartment - and this is for young workers with cushy, formal sector jobs. For the 40% of the population that works informally, the cost of housing is even steeper, and they usually tend to be forced into housing that is either insecure in tenure or not suitable, or both, in the informal sector. So it’s obviously the high cost of housing - but like, that’s not an answer. Why can’t people afford housing?

I think an important thing to note is that “why can’t people afford housing” and “why are housing prices high” are not always the same question - they usually are. Housing, in every society in the planet, costs multiple times the annual income of a household. Most people don’t have multiple years of income in cash on hand - they tend to borrow money and pay it back with interest, to smooth out consumption. A really big problem in Latin America is that it’s just really hard to get a mortgage: the main cause is, basically, economic instability - countries had, until fairly recently, really big bouts of inflation and recessions that made loaning overly risky. In Argentina, financial instability in particular was a massive issue in the 1990s and early 2000s, which left a sour taste on the mouths of policymakers and consumers alike. Secondly, informality means that a lot of people who do make enough to get a mortgage either have no proof of their income, or don’t have stable enough earnings or employment to ensure they can pay. Thirdly, a lot of countries just don’t have good regulations on banking and prudential stuff that makes lenders a bit queasy about extending long lines of credit. Though most other countries in LatAm have made some leeway on economic stability, prudential regulation, and tailored programs (for example, inflation-linked credit), Argentina hasn’t. And broadly, the fact that getting a mortgage is really hard means that only people who make a lot of money get them, which incentivizes overproducing high-end housing and underproducing “affordable” units.

Here’s where supply breaks in and, to the surprise of nobody who reads this blog, I think it’s the cause of housing costs. Regulations do play a role but also the housing market in Argentina does have significant imperfections that also matter: as mentioned above, credit rationing also leads to overproduction of “luxury” units. There’s also bad government policy involved: for the longest time, the public sector focused its housing policy on building public housing through FONAVI (the National Housing Fund), which was ridiculously expensive and also very badly targeted (because informal workers were usually not elegible). But the real issue is, of course, the lack of housing and land supply. Wait, land? Isn’t Argentina a massive country? Well, yes, but what matters is serviced land (as in, hooked up to public services) and for a number of reasons (more on this later) governments have just not been very good at doing it, which meant that pretty substantial tracts were just left empty.

Here’s where it’s useful to divide the City of Buenos Aires and the rest of the metro area (the Conurbano). The city has generally good housing policy (zoning, etc) and it developed and serviced most of its plots of land, but there was fairly low demand for living in the Southern part of the city because it’s far from amenities, far from employment (basically all jobs are concentrated in the microcentro, the central business district), and just poorly served by public transportation or major roads. So it zoned a lot of it industrial with the expectations that eventually factories would go there, they didn’t for complicated macroeconomic reasons, and instead the land was taken by squatters, who also settled in, for example, abandoned landfills or railway yards. Outside the city, the situation is different: in 1977, the Province of Buenos Aires basically set zoning policy for the entire province by fiat3, and it imposed extremely strict rules on how to service lots, high minimum lot sizes, significant density restrictions, and a fairly low floor to area ratio. And municipal governments add in their own rules, which are usually stricter in richer municipalities because they don’t want poor people from nearby towns to move in. So obviously this resulted in lower housing supply, but it should be noted that “NIMBY” types who want to hoard housing and not build anything are a pretty important confounding factor - richer areas both have stricter zoning rules and higher prices than poorer ones. But one of the most important factors (also true for California) is that it’s just really hard to get a permit approved, which I’ll come back to but is usually because of NIMBYism, but in some cases it’s genuine incompetence by city governments.

Okay, but there seems to be a step missing here. In the US, restrictive zoning leads to more expensive homes which leads to more homelessness. So why even is there a black market for housing? The answer is that developing economies also have a big informal sector of the economy, which is basically a part of economic activity that doesn’t follow any laws. Traditionally, there’s been three (not very easy to differentiate) positions on informality. The first, from Nobel Laureate Arthur Lewis, (who is one of a handful of non-First World economists to win the Prize), is the oldest one, and it’s referred to as “dualism” - the idea is that developing countries have structural issues where some parts of the economy (and the country) move into manufacturing and later services, but other parts stay behind, which means that there’s a formal, modern economy, and an informal, traditional economy, and the two have little overlap. The second view, which is highly complementary, is that the informal economy isn’t a marginal part of the economy, but an important one - basically, that a lot of economic activity that could be legitimate is instead channeled through “illegal” relations as a way to drive down costs for employers and other parties with market power. The third view is called “legalism”, and it’s basically the idea that people either chose not to be formally registered to not pay taxes or because regulations made it too costly, or an idea strongly associated with a guy called Hernando de Soto4, where informality is both because of government incompetence and because of economic backwardness - basically, bad government policies caused very poor people, who had assets (land, homes, vehicles) to not have formal property deeds, and that held back the development of formal economic relations around them. The three are kind of true (especially for different types of economic informality), but the first point is that the informal economy should be staggeringly unproductive, the second is that it should be very productive, and the third is that it should be kind of the same, and it turns out that estimates of GDP in Barrio Padre Mugica are just 30% of the same activities in similar plots of land in the formal sector, which kinda makes the first view the most appealing.

El Estado es una mierda? El Estado es clave!

The slang term here for something done informally is barrani, which comes from Ladino (the Sephardic version of Yiddish) and means, well, informally. The relation between the regular and the barrani housing market is extremely complicated - and it’s mediated by regulations and by housing market outcomes. Basically, we can see that stricter land use causes housing affordability to go down, which in some cases decreases demand but in Latin America, where the population, job market, and economy centers around a few major cities, this isn’t very dissuasive.

The defining factor seems to be how likely the government is to kick the prospective settlers out (areas with more strictly enforced land use have both higher costs and more settlements), which relates to the previous factors (vacant land, housing costs, etc) as well as some general government quality - in particular, some governments just choose not to disperse settlements because it means that low income people go somewhere. Fundamentally, it just appears that people will live somewhere, and that the somewhere is going to be chosen either at the formal or informal margin based on price. And if you choose informal, you have a choice between living in far-off, backwards municipalities that don’t enforce their own zoning laws, or in settlements in or near the City where you can go to your regular job.

What should the government do here? Well, as I’ve mentioned, the proactive approach seems better than the remedial approach, firstly because it’s just way cheaper (it costs six times more to service a lot before its settled than to service an informal settlement. Additionally, the “sites and services” approach seems to… not work. The neighborhood improvement program (PROMEBA) doesn’t seem to pay off in any tangible way, and lot titling efforts have modest benefits at best and are generally completely ineffective due to bad implementation.

So like there’s a lot of options to address housing affordability, but the solutions for Buenos Aires specifically seem fairly obvious. First, the metro area has horrendously uncoordinated urban policy, with land use being completely incongruent with mobility access or broader metro level goals - for instance, the ritzy suburbs in Zona Norte just straight up don’t have density near railroad and bus infrastructure (or highways). The metro area also needs to connect the City and the Conurbano, and the North and South of the metro area with new and expanded infrastructure. Third, they need to clean up the settlements in some way, with the support of the local community, to integrate them into the economy5. And last, they need some sort of comprehensive policy plan to provide services and green spaces at the metropolitan level, because the complete lack of joint planning leads to extremely bad distributions of space and in very sprawled out and energy inefficient urban forms. The City of Buenos Aires, for example, is planning a big investment in a new subway line (the F line) connecting the central business district to both residential areas up North and in the Southeast, as well as a “trambus” (I have no clue what the fuck that is) encircling the City. They also changed the zoning code to eliminate floor-to-area requirements, raise maximum heights, and make developers pay a “land value tax” on unused vertical space, and cooked up a scheme called “Additional Constructive Capacity” to let people who develop property in the South add extra square footage (technically cubic footage) up North. They’re also planning a bunch of developments in the southern part of the city to get people moving there, including expanding light rail.

But nobody else is really working on this angle. And it’s not necessarily because they don’t know what to do. The issue isn’t really that the technical solutions aren’t known or that there’s significant disagreement - it’s that, plainly, nobody can or wants to implement them. A first step is obviously intentional inaction: corruption is very common in the area, and municipalities have a lot of incentives to either let settlements develop (as a way to provide affordable housing for poor people, and also because of links to organized crime), or to not implement a coordinated urban plan - for example, the former mayor of Vicente López and current mayor of Buenos Aires was routinely criticized for granting lucrative zoning variances to politically connected developers, who built stuff that went against the “character of the neighborhood” (lol) but also, more importantly, had no servicing put at its disposal. A lot of municipalities also can just choose not to follow laws that allow them to build more units - in California, the government of Beverly Hills isn’t permitting anything in order to protest laws requiring them to build more affordable housing.

But a second issue that I think gets overlooked a lot isn’t lack of wilingess to execute, but rather, lack of capacity. As I said, the City is undertaking some pretty complex projects to expand infrastructure, incentivize development, and capture land value - and they’re still kind of half assed and brochure-y. The municipalities just don’t have the ability to do even that. In one example, the municipality of Moreno developed a pretty comprehensive plan to urbanize in a balanced way, and then proved completely incapable of executing it (more on this later). Of course, the overlap is actually quite significant: first, because lack of administrative capacity is a policy choice (in particular, the choice to permit less) and a potential avenue for corruption. Second, some people just don’t want to: the municipality of General San Martín straight up told researchers it thought that having a standardized approval process was asking the wrong questions and it valorizes white institutions and white ways of knowing and being and structuring society in really problematic ways.

I think the apple’s rotten down to the core

But there’s another layer of problems that I think is much more mundane, and much more urban in nature: scale. Cities exist because of economies of scale - because it’s more efficient and effective to produce within large numbers of people who are also potential customers. But while cities organize themselves in ways that are economically motivated, politics organizes itself in… other ways.

The Buenos Aires metro area is spread out between 41 municipalities in two different provinces. So there’s already two levels of government: local, and provincial (in the City, they’re the same) - without considering the third player, the national government. Argentina is a federal country where the government provides significant funding to the provinces6 (in part to fund education and healthcare), and in the Province of Buenos Aires, provincial funds also get distributed to municipalities. But there’s still direct national involvement, for example in running national universities, national hospitals (the Garrahan in the City and the Posadas in the Province, to name two), and directly in running the national railways and regulating bus fares. This gets really messy really fast: the government fixed bus and train fares since early in Milei’s term - the price of a train ticket is actually half the cost of processing a train ticket. If you pay for the train and don’t get on, the government still loses money. Meanwhile, the City wants to keep prices stable to pay for repairs and defray the F line’s cost, but the fare differential means that it has lost 54% of subway ridership to buses and trains.

The reality is that levels of government don’t cooperate badly - they just don’t cooperate at all. A lot of this is petty politicking - the City is an easy way to get into the national spotlight, and the City, province, and nation have only been governed by the same party for 4 of the last 30 years. For example, the City cut a deal with the national government to lease CENARD (a high performance athletics institution) the empty facilities from the 2018 Youth Olympics, and free up their old parcel up North. This deal fell through basically immediately after the national government changed hands in 2019, and the space was leased to private sports leagues instead. There’s also endless squabbling over the transfer of police responsibility, funding for (formerly) nationally-run institutions, and most importantly, usage of public City services by people from the Province (which, AFAIK, is legally required). It doesn’t help anyone that the Province of Buenos Aires is massive: each of its electoral sections (multimember districts) in the metro area by itself would be the largest province in the country without counting the rest of Buenos Aires. And this behemoth is also, well, in the shadows: the provincial government is notoriously not transparent, and this is badly serviced by the lack of provincial level media, so there’s a substantial gap between (dying) local media and City-focused national outlets.

At the municipal level, the picture is… even worse. There’s basically only one bright spot: CEAMSE, the metropolitan waste management company, which is run jointly by 45 municipalities and the City of Buenos Aires. Basically it’s a municipal body that manages to be jointly managed, and it’s quite literally the only successful example of joint municipal coordination - except that while the economic costs and benefits are internalized, the social ones are not, because General San Martin singlehandedly has to face the problems posed by informal settlements around the CEAMSE landfills. At the same time, provincial laws are ridiculously badly tailored to each municipality: Almirante Brown could densify in Adrogué (its largest and nicest city), but historical conservation laws on the city center make it infeasible. There is also no municipal body coordinating land use and/or transportation or other important forms of infrastructure or public services. In fact, utilities like electricity and running water are run by the national government, which is, let’s say, a shitshow - for example, Florencio Varela was trying to develop new land to prevent settlements, and the government slow walked infrastructure works for random reasons. The authorities of Tres de Febrero actually invested substantial sums of money to get its own corps of professional employees, and it used a mix of that and land value capture to start self-funding infrastructure to not need to wait around for the government. Everyone else has to either wait around, lobby someone else, or borrow from like IADB and the World Bank, which also needs a lot of competence in the government.

The problem with a lack of coordination is that, again, economic factors operate at the metropolitan, and not the municipal, level. The key forces are agglomeration and congestion - basically, people want to live as close to work as possible without having to live with too many other people. Transportation infrastructure means that they can travel further in the same time, allowing cities to spread out. But this causes metropolitan-level issues: when Pilar was connected to the city by the Panamerican highway, it took advantage of the speed of connection by permitting a bunch of industrial parks and gated communities7. This increased housing demand for low income groups too, who couldn’t live in fancy country clubs obviously, so instead they went to nearby Moreno. And Moreno was actually prepared, because it developed a pretty innovative system of municipal land banks, planned servicing and development, and land value capture… that completely fell apart because of inability to execute, lack of coordination with the national government, and the fact that IDUAR (the land bank corporation) and the planning office failed to coordinate on action for 18 years.

Conclusion

Because of the global housing affordability crisis, leading to irregular forms of settlement in developed countries like homeless encampments, it’s possible that the experience of and recommendations for Buenos Aires would also be applicable. But even if that won’t really be the case, informality is still a huge issue: one in five people in the world live in informal settlements. This appears to be an insurmountable task for Buenos Aires: high political polarization, urban policy and the urban agenda not being a major concern for politicians, and inadequate institutional design coupled with low institutional quality make implementation difficult.

The main stumbling blocks are not an incorrect idea of the situation, but rather, the lack of political will. In their best-selling 2012 book Why Nations Fail, Nobel Laureates Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson write “...poor countries are poor because those who have power make choices that create poverty”. This is also applicable to cities. The solutions already exist: joint planning of land use policies, and coordination on public services, infrastructure and transportation, as well as development of state capacity and participatory channels for community involvement and outreach, which would allow the metro area to channel its informal housing demand into low-cost, formal sector options with access to employment and amenities. In Buenos Aires, it is possible to develop a pathway forward - if the political will appears.

This gets really complicated but: the official definition of the Buenos Aires metro area includes 40 municipalities, but the website linked uses two (AMBA and RMBA) which leave out around ten each - including, in both cases, the La Plata metro area. So discrepancies with the link are due to “including stuff like Ensenada”.

On average in 2012 it cost ~11,000 dollars to service a lot via PROMEBA, plus 15% in indirect costs; adjusting for 39% cumulative inflation and estimating it for 1.2 million informal households in the whole country - I’m assuming one household per lot, which is reasonable because multi-story lots (which exist!) probably cost a lot more than single-story dwellings. It adds up to around 21.9 billion dollars, and would be 9.6 billion for the Buenos Aires metro only, or 0.3% of the metro area output (a fun note is that the share of population is 35-45%, and the share of GDP is 35-50%, so I’m just assuming the two cancel out. But it’s not higher than 0.5% or lower than 0.1%).

Before that, it wasn’t common for municipalities to have like, land use and whatnot. I know this because my grandma used to work for the municipal government of her small-ish hometown and they sent her on a work trip to the beach resort of Mar del Plata for her and planning staff for every municipality in the province to get trained in how to apply the new law. The story is that my grandfather wouldn’t be able to take care of the kids, so they provided childcare (some other lady from the office) to look after my mom and uncle/aunts.

De Soto is kind of an interesting character in this because his recommendations are basically in line with the “deregulate everything” theory but his diagnosis is actually different. His book is pretty good but it’s also pretty dated (it’s from 1977)

One way to do this would be to do improvements on every salvageable settlements and the ones that are on landfills, floodplains, etc just offer them to move with land readjustment, a system developed in East Asia to get people who own very small plots of a large tract of land to move somewhere else by giving them an equal share of another valuable project. While the linked article doesn’t really mention settlements, it’s been discussed a lot. Also if you pay a lot of attention you might realize that Japan does something similar to CCA.

This gets insanely convoluted really fast but Argentina has a system known as “tax coparticipation” where the government collects all national taxes and distributes it between itself and the provinces as part of a compromise to unify tax codes in the 1930s which didn’t involve anyone suing the government because indirect taxes weren’t in the Constitution. In the 1980s Buenos Aires (province) ceded part of its cut for really convoluted political reasons. The City gets its part out of the federal share, because it didn’t have provincial status until the mid 1990s, but it matters less because it has a lot more self funding (because it’s much richer than the rest of the country).

I haven’t talked about them but they’re a massive issue in large part because they’re not actually coordinated between municipalities or by the province. This becomes especially serious because they tend to prevent water drainage in tributaries of local rivers, so they worsen flooding in informal settlements nearby. They also tend to damage local habitats, leading to really fun sights like capybaras invading Nordelta country club.

Well, there’s a huge elephant in the room you’re omitting: in the City of Buenos Aires, a large portion of the settlers are foreigners, the result of a hugely idiotic mix of unrestricted welfare state and totally open borders (plus being surrounded by way poorer countries).

So there’s another solution you don’t mention: saying goodbye and covering their ticket back home. Sorry if that doesn’t sound very humanitarian, but taking care of another country’s poverty as your own social policy isn’t some noble ideal, it’s just plain stupidity.

In my opinion, when anyone discusses long-term politics in Argentina, it's impossible not to remark that its economy is a roller coaster. Until the country solves this question, it will never have a viable politics of anything.

Another thing is that urbanism requires compromise and initiative. I don't see that in Argentine politicians (maybe because of the thing that I wrote before).

PD: What do you think about land value capture taxes like "Plusvalía urbana"? I think that damages the price system. It's better to have a property tax linked to land value or FAR indicator.