Argentina, reliably, did the thing.

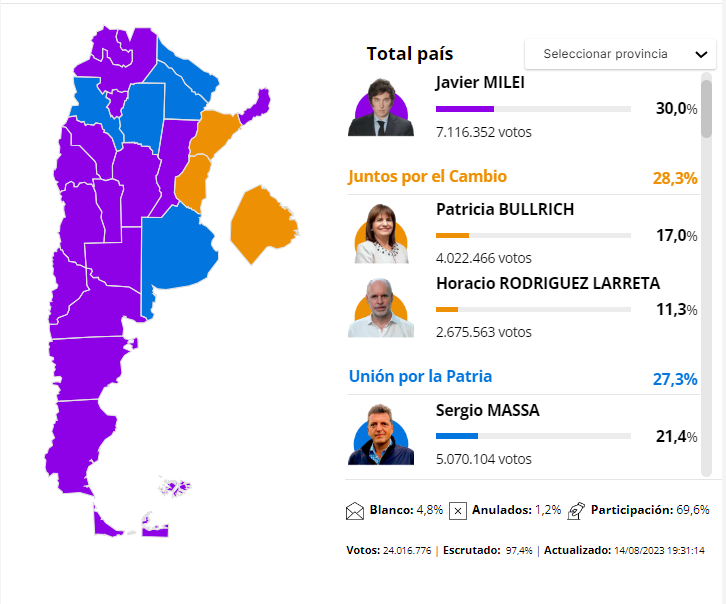

Against all odds and polling averages, which predicted the governing Peronist Party and the opposition bloc Juntos por el Cambio to run neck-and-neck in the mid 30s and libertarian economist Javier Milei to get a distant third with 15% of the electorate, Milei won: he got 30% of total suffrages, versus 28% for Juntos and 27% for the government. The much dreaded “three thirds” scenario materialized unexpectedly, leading to a complete meltdown in the currency market: the official exchange rate was devalued 22% overnight the day after the primaries, while parallel rates went up by roughly a third in the days since (from 600 to 800 pesos). The central bank’s reference rate soared as well, from 97% to 118% (still below the projected 150% annual inflation).

So what’s going on

Mad as hell

That Milei won is perhaps unsurprising, given the state of the country; what is surprising is how big he won. The scale of his victory cannot be understated: he combined the worst ever result for the Peronist Party with the biggest victory ever by a third party, winning 16 of Argentina’s 24 provinces and coming in second in four others.

Mieli’s 30% of the electorate is roughly constant across income levels, age, and partisanship - although he seems to be favored by men over women. The libertarian candidate won in some of the country’s richest regions (Patagonia) and the poorest (the rural Northwest and Northeast); he did well in the productive central region as well. The only places he did not perform well have been the traditional battlegrounds of the Buenos Aires metro region and the Province of Buenos Aires, where he came a distant third - just as the polls expected, although outperforming the 2021 midterms.

Why did someone so outside the mainstream win so big? People are, unsurprisingly, fed up. The Argentine economy has fared badly for a really long time: inflation rates have been in the double digits since 2005, and in the triple digits for the better part of the year. GDP has not grown in 12 years, during which the economy has alternated between shallow recessions and equally shallow recoveries ever since. Real salaries have declined by around 15% in the past five years. Taxes and spending have both gone up without any visible correlation with quality or quantity of the services provided.

Similarly, the traditional party of working-class people, the Peronist party, has spent the better part of a decade embroiled in increasingly serious corruption scandals for its figureheads, meaning that trying to bring the judiciary to heel has taken up a disproportionate part of its agenda. The opposition party has not managed to steer the economy either, and its major figures are all notoriously ineffective, uncharismatic, or both. At the same time, the perception is that crime has soared, and that nobody provides either a solution or a credible response.

It’s not surprising at all, then, that the people would turn to a populist outsider with big promises and unconventional proposals to make things right: what’s surprising is how long it took, and what kind of person took over. Milei is a hardline economic libertarian and a vaguely socially conservative figure, in alignment with even more hardline reactionary types. This goes against the grain in Argentinian politics, which are generally left-leaning and generally progressive, at least compared to other similar countries.

Exactly how the rest of the election season will pan out is highly uncertain: turnout was 6% lower than in the previous election season, and “blank” votes (for no candidates) were high - roughly 6.7% of the electorate did not vote for anyone, either by not showing up or not choosing a candidate. A bunch of legislative and gubernatorial elections had large swathes of the vote be blank, simply because there was nobody on Milei’s ballots for that election - in Santa Cruz province, Milei’s win + record-high abstenteeism meant that more than 60% of ballots were blank.

Back in the 1970s, this economic/political commentator named Marcelo Diamand wrote about something called the Argentinian Pendulum - a sequence he observed in economic policy and politics. To him, politics had three thirds: the peronist party, which represented the lower classes and was more economically populist; the opposition (and, back then, the military) which favored the laissez faire views of the upper income sectors and of the central farming regions, and a middle class that switched from one to the other in defense of its economic position.

Diamand’s view on the economic implications of this dynamic was that each of the two diagnoses might work (he didn’t think they did, for what it’s worth) if each coalition had sufficient power to impose it, but they did not because they structurally blocked each other - politics had its own weights and balances beyond the consititutional ones. This is similar to what political scientist Guillermo O’Donnell called “The Impossible Game” (in game theory form, for the nerds): it is impossible to form a government that will reform the nation without Peronist buy-in, but it is not possible to do so credibly with the Peronists. His own view of the economy was also contentious (I don’t agree with his views on the fundamental issues, but that’s beyond this post), but the TL;DR was that the left’s vision was not compatible with the actual structure of the country’s and the world’s economy (ouch) and that the right’s vision was incompatible with politics - the left wanted a real exchange rate that was way too high to be economically feasible, and the right wanted a currency whose value was too low to be politically acceptable.

I am not going to review this framework, but I think there is some truth about the political dynamics described, which makes the Milei phenomenon even more baffling: he doesn’t actually come from the right bloc, but instead from the mittelstand itself; the middle third. He punctured each coalition by taking a couple of points from their floor of 33%, but the bulk of his electorate seems to come from the middle of the country: the undecided middle class and small business owners fed up with crime, inflation, corruption, and an increasingly incompetent political class.

It’s a Party in the USA - Milei Cyrus

What are the actual, concrete stakes of the election? Well, the three major candidates all have roughly different visions of the same process. Peronist Sergio Massa’s policy platform is vague at best, but he seems to be pointing towards some manner of mild and graudal economic reforms. Juntos por el Cambio’s Patricia Bullrich appears to be more hardline, with a more drastic plan to reform the public sector and solve the monetary issues plaguing the country, although implemented somewhat progressively.

All three (major) candidates (plus hanger-on Juan Schiaretti, who is intent on capturing the Anti Peronist Peronist demographic) agree on roughly two issues: reforming the government, and labor reform. Fiscally, everyone seems to agree on reducing spending (which is mostly made up of electricity, heating, and water subsidies, which go overwhelmingly to the richest in society) and on cutting taxes to some extent, especially for businesses and on agricultural exports. This is all fairly reasonable and obvious: the deficit has been monetized for the past ~3 years, resulting in runaway inflation, and taxes are indeed too high.

Labor-wise, everyone has agreed on simplifying hiring and firing, replacing the current severance system with the construction sector’s model: sectoral, union-managed funds where workers and employers make contributions, and which are released once the employee is fired. This is pretty stupid: imagine a sectoral downturn - the fund would be depleted pretty quickly, unless it was too large precautionarily. In a recession, it would be worse, because recessions definitionally affect all sectors of the economy - so there wouldn’t be any sectors standing. Of course, it also seems (based on the superficial mentions of these designs) that employees would be disincentivized from switching sectors to preserve their unemployment funds, which is also nicht gut. The design of such a program can also not change because it has to be union-managed so they don’t burn down the country in protest - healthcare reforms in the 1990s were managed by simply giving them loads of money, too.

The last item on the agenda is monetary reform. Massa and Bullrich roughly agree on getting rid of currency restrictions and devaluing the currency, although how and when are the big conflict points. The currency market, right now, is under extreme controls to protect a massively overvalued exchange rate without draining the Central Bank’s paltry reserves. There’s roughly two (corner) options to transition from the current regime to a normal one: a free market with export taxes to prevent pass-through into prices, or a bifurcated exchange rate for trade (lower) and other operations (higher). The point for either is that a sudden devaluation would be profoundly destabilizing at 100% annual inflation and a threadbare level of output. The first solution has a few technical hiccups, but it also props up the Treasury at the expense of the trade balance; the second solution is “cleaner” and easier to wind down, but very administratively complex, and is specifically disallowed by the IMF.

Javier Milei’s solution to the monetary question is, to put it somehow, more colorful: dollarization. Follwing the example (or, according to the Ecuadorians themselves, warning) of Ecuador, Milei would simply replace the national currency with the US dollar - or, according to Paul Krugman, the Euro1. I’ve already written (negatively) about the general idea previously, which is basically that dollarization does not solve any problems that other monetary arrangements can’t solve themselves and can only work under preconditions that allow any other monetary arrangement to work. It’s also worth mentioning that Ecuador has not been a success story and the only other Latin American country to attempt to stabilize its economy through either partial or full dollarization of the economy was Argentina, with its disastrous Convertibility regime (I’ve written it up in both Spanish and English previously) - meanwhile everyone else just pulled it off with monetary and fiscal reforms.

Let’s get a bit into the weeds: how does dollarizing the economy, like, work? Basically, you need to turn the entire balance sheet of the Central Bank into US dollars. That means that monetary aggregates need to be backed by the US dollars that they’ll be converted too, at a given exchange rate. I used to think that the question of what exchange rate to dollarize at was kinda stupid, because you’d just adjust rates to increase the supply of USD, but it’s actually very important: if the economy doesn’t have a sufficient amount of money (which you’d get by dollarizing at too high an exchange rate), you simply get a recession, and in this case it’d be a really big one. But you also can’t lowball dollarization: if you picked a low exchange rate to dollarize at, it’d be instantly non-credible, and you’d send the economy into hyperinflation because everyone would dump the peso in favor of the dollar, which pushes up the exchange rate and therefore both raises inflation and devaluation expectations and raises costs for businesses. Which is why nobody is really proposing this (the exchange rate could be as high as 2000 pesos), not until the economy is stabilized by reducing the Central Bank’s liability sheet and increasing its reserve stock2.

How big a lift would it be to convert the Central Bank balance sheet into USD? Well, the Central Bank has roughly 26 billion US dollars in reserves, but net reserves (i.e. if you subtract gold, various weird deposits at international institutions, and IMF shitcos) then they’re at negative ten billion, and if you take out some Chinese currency stuff they’re at negative fifteen. Ouch. Meanwhile, the money supply (and you have to get to the really galaxy brained aggregates here) is so big that only an exchange rate of 2000 pesos would balance out the reserve stock - and the official market rate is currently at 350. And the Central Bank’s balance sheet gets more and more bloated every second because the main factor of monetary expansion is paying off the Central Bank’s debts… which are growing because the Central Bank needs to offset all the money it printed to pay off its debts… and it offsets that money by borrowing more.

Roughly speaking, and after considering all of the above, it’s estimated that the Central Bank needs to find 35 to 45 billion USD to clean up its act and manage dollarization without hyperinflation. So what are the actually feasible routes to scrounge up enough USD to dollarize the economy? Broadly speaking, Milei’s team makes three different cases:

[handwaves]. The first option, which is the most gradual and/or unrealistic, argues that they could reduce the Central Bank’s real balance sheet (either through tight money or through higher inflation) and boost its reserve stock (mainly by securing some kind of loan) until dollarization can occur at a reasonable exchange rate. It’s unrealistic because the only such loans could come from China (who hate Milei and he hates them) or the IMF (who don’t like the idea of dollarization very much), but it could be the gradual path to dollarize after the economy brings inflation under control.3

Take everyone’s money but like, in a libertarian way. A second option goes as follows: there’s roughly 35 billion USD in bank deposits, loans to exporters, cash held by banks, and mandatory deposits by banks in the Central Bank to back up the USD deposits. So that means that you only need a small loan (and also to take all of that money but like, in a libertarian way) to make whole. OR, conversely, there’s roughly 300 billion in USD cash that people hold for a variety of inflation related reasons (and also “the government taking everyone’s money” reasons), which Milei’s advisors think could be used to some extent. This money is technically illegal, because buying USD cash is not usually registered, and Milei’s advisors think that some of that could be channeled into the financial system. Of course, most people hold such stocks of currency as savings, and trying to conflate savings with liquidity feels like a very 1920s kind of reasoning. Also the plan of taking everyone’s dollars is known as the Bonex Plan because the government replaced everyone’s dollars with shitty government bonds back in the 1990s, and it’s one of the reasons nobody trusts banks anymore.

Sam Bankman-Fried’s 45 billion dollar IOU. The last idea is as follows: the Central Bank has a boatload of assets, particularly government bonds. Valued at a 30% discount and converted at a semi-reaosnable exchange rate (around 800 pesos in today’s money), they add up to roughly 75 billion, which would cancel out the Central Bank’s 30 billion balance sheet plus another 45 billion to turn all the economy’s cash into dollars. EXCEPT that actually, if you look at what the Central Bank actually holds, it only has roughly 21 billion in assets, and then the other 75 billion are a variety of fake bonds with fake values that the government invented so it could pretend to sell them to the Central Bank and then get real money in return4. So the Central Bank needs around 40 billion in new money anyways. Some economists want to add in some corporate stocks and bonds the Treasury owns for a variety of reasons, but there’s not 40 billion in new money anyways and a lot of the existing debt would have to be unilaterally cancelled, which is not exactly how you stabilize the economy.

So, this doesn’t seem like a very workable solution, but I’m open to being surprised.

Apres moi, le deluge

The political situation is so difficult precisely because of the fractious nature of the results: the three major candidacies are all virtually tied with each other, with turnout and blank voting resulting in an incredibly unpredictable election space. Each of the candidates directly competes with each other: Milei and the opposition’s Patricia Bullrich battle for the right wing vote, while Bullrich and peronist Sergio Massa will go after the political center, and Milei and Massa will quarrel over the youth vote, and lower income voters.

Fundamentally, the election will result in the weakest government since democracy was resumed in 1983 no matter who wins: gubernatorial elections and primaries will result in 11 territories controlled by the opposition, 8 by the Peronist party (its lowest ever number), and 5 by provincial parties. In the lower house, Milei’s party will have 39 deputies (roughly 15%), while Juntos would have around 106, and Peronism 94, with the remaining 18 corresponding to various smaller parties. In the Senate, nobody will manage a majority without smaller, mostly peronist parties: the libertarians will control 8 seats, while the opposition will have 27, and Peronism will be represented by 35 Senators - each bloc a few short of the 37 required for a simple majority.

This is not a stable combination for any kind of government, but especially not one led by a charismatic populist outsider who constantly rages against political elites and claims to be the one providential leader who can alone fix the country’s issues. To quote Juan Linz’s seminal piece on the Perils of Presidentialism:

The plebiscitarian component implicit in the president’s authority’ is likely to make the obstacles and opposition he encounters seem particularly annoying. In his frustration he may be tempted to define his policies as reflections of the popular will and those of his opponents as the selfish designs of narrow interests. This identification of leader with people fosters a certain populism that may be a source of strength. It may also, however, bring on a refusal to acknowledge the limits of the mandate that even a majority to say nothing of a mere plurality—can claim as democratic justification for the enactment of its agenda.

Linz’s point is that, under a presidential democracy (like Argentina, or the United States), the president and the legislature both independently draw power from the electorate. If the President and the Legislature aim in different directions, they both have clear democratic mandates to power, and there is no way to democratically resolve the conflict. This dual legitimacy inherently leads to conflict that cannot be resolved: there is no way, in a democracy, to ascertain who has the better claim to power between two equal branches of government, at least not in a democratically legitimate way. The President may attempt to mobilize his supporters and become openly hostile to the opposition, and at the extreme, could attempt to resolve the conflict through violence.

One such extreme example is Alberto Fujimori’s 1992 autogolpe. Fujimori, an inexperienced outsider running on a platform of economic reforms and reigning in crime and violence (especially left-wing militias that were commiting various atrocities) secured the presidency of Peru, but did not receive a majority or even a plurality of the seats in Congress. After a series of incidents where congressional leadership blocked Fujimori’s proposals, the President simply decided to dissolve the legislature and the judiciary and proclaim himself dictator with the support of the military. He continued to rule as President for three more years, mainly by seeking legitimacy through plesbicites - including one that supported a new constitution that curtailed congressional powers and allowed him to stand for reelection.

Conclusion

Right now I’m pretty certain that Milei will win the election, which I’m not particularly happy about. Even if he won outright in the first round of voting (which is feasible but not likely5), he would still have under a quarter of either house of Congress, and the Senate would remain a major roadblock: all inroads for Milei would come at the expense of the (likeminded) oppositon.

Andrés Malamud, one of the country’s foremost political scientists, says it’s not going to be pretty for Milei, and could easily become thorny, constitutional-order-wise (Peru-tier thorny). Do I really think that Milei is going to usher in hyperinflation and also become a second Fujimori? Not really, but, to quote Oppenheimer, there is a near zero probability of it. So like, let’s be careful around the guy with the crazy hair.

Quick fact check of Krugman: Argentinian trade is roughly 1/8 Brazil, 1/8 China, 10% EU, 10% US, rest a bunch of countries (mainly LatAm and East Asia). Meaning that the Brazilian Real or the Chinese Yuan would be better, trade wise, than the Euro - not to mention that the remaining 75% of Argentinian trade is USD denominated anyways.

Interestingly, the market exchange rate of 798 pesos is roughly where the parallel rate landed after Milei’s win… EMH bros are we back?

The case for why you’d dollarize if it’s not to reduce inflation is more political economy in nature, but at least plausible in theory.

If you can spot the problem you win a one-way ticket to the Bahamas.

In numbers: abstenteeism + blank voting was roughly 6.7% above 2019 levels. If turnout rises according to normal patterns, the number of voters should increase by roughly 5% (it went from 75% to 80.8% in 2019). That means that Milei could attempt to reach around one in eight elegible voters who didn’t cast a ballot for anyone so far in 2023 - and you only need to cross 40% with a ten point lead to win without a runoff.

If you want to get into the horse race weeds: Milei has a good geographical distribution of the vote because he’s only underperforming in Buenos Aires, which is underrepresented in Congress. So his vote share translates more or less proportionately into seats, and since the Chamber of Deputies is renewed by half every two years then he’d convert half his share of the vote into seats (plus two, since he already holds those from his 2021 midterm showing) - meaning that with his current 30% he’d get 15% and change of seats, largely at the expense of Peronism because the D’Hont system advantages the largest parties. Juntos is less harmed, because the 2019 legislative results were brutal for the party.

The Senate is oddly apportioned for various historic reasons that don’t come into this, but there’s 2 Senators for first place finishes and 1 for the runner up; he’d get 2 in Jujuy, 2 in San Luis, 2 in La Rioja, 1 in San Juan, and 1 in Chaco, plus he drained enough votes from JxC to cost them 1 seat in Buenos Aires and 1 in Santa Cruz (libertarians didn’t run candidates in those). Meaning Milei gains 8 Senators largely from JxC and smaller regional parties, and Peronism has no net change (they win two in Buenos Aires and Santa Cruz, and lose two).

One thing you should’ve addressed regarding dollarization is that a major part of the justification by its proponents is rooted in that same political analysis.

Precisely because many of the ideas of the Peronist party are incompatible with reality and because they will eventually win again, getting rid of the country’s monetary sovereignty is why they think it would be good for Argentina (and bad for any country with credible monetary authorities).

Dollarization is an attempt at rendering monetization of the deficit impossible. And while economists and many politicians are not happy with the results of dollarization in Ecuador, the population itself is extremely pro-dollar and reversing it is politically infeasible.

I think people who argue from economic theory, without accounting for the political equilibrium of Argentina, are being naive. Credibly fixing Argentina’s central bank is less likely to succeed than dollarization, and both are unlikely to succeed.

Great read, but the market moves you described in the beginning (peso devaluation and rate hike) were already scheduled under their IMF program: https://x.com/generaltheorist/status/1695907743675122120?s=61&t=jSfZnShgGR4uH28s_gVS6g