Going Green

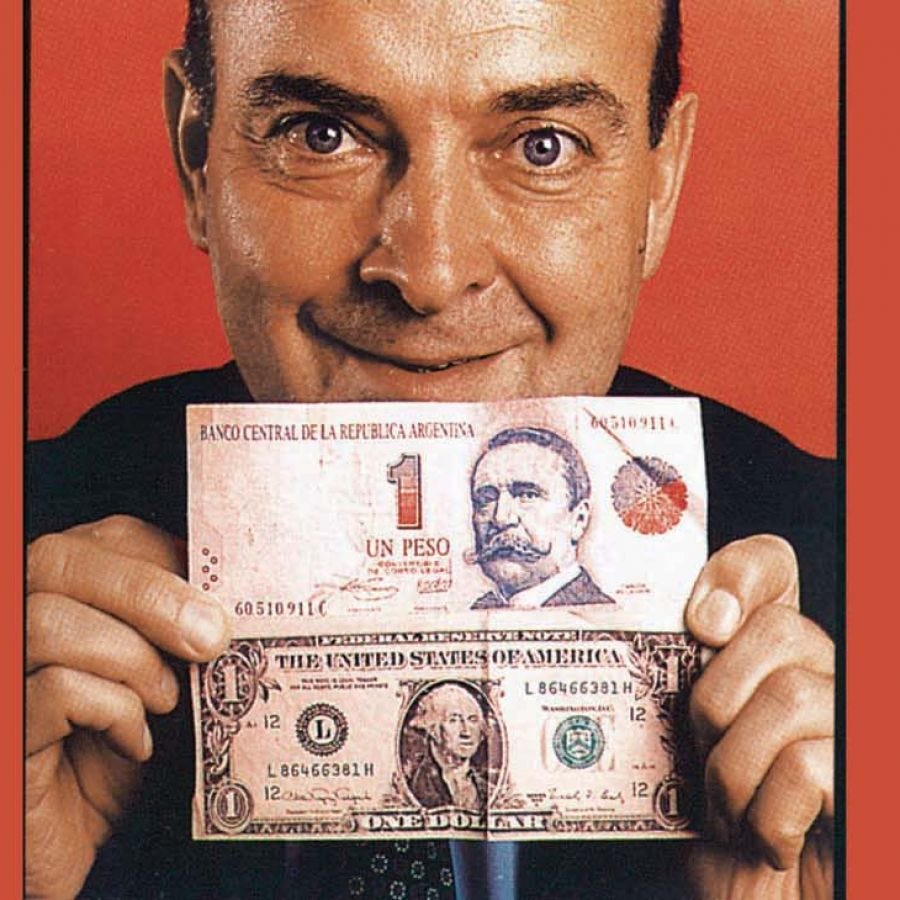

Can dollarization solve Argentina's issues?

Argentina, as you might be aware by now, has plenty of monetary issues: the country's persistently high inflation has become the stuff of infamy worldwide. Currently at the 50% mark and with no ceiling in sight, politicians are looking for less and less conventional solutions, from price controls to national food distribution companies.

Last week, for whatever reason, economists discussed one even more drastic solution: dollarization. In practical terms, dollarizing the economy would mean scrapping the currency, the peso, and only letting US dollars be legal tender. Is this a good idea?

I see seas of green

How would dollarization work? Generally speaking, you would eliminate the ability of the Central Bank to issue currency, and instead utilize US dollars exclusively. There would still be an extremely limited scope for monetary policy, but in broad terms you no longer have independent control over it - it is de facto set by the Federal Reserve.

This would have a number of implications. The first is that, absent some agreement with the United States, the amount of currency in circulation would depend exclusively on the existing stock of hard currency in circulation and on the Balance of Payments. That is, instead of monetary policy being capable of increasing the amount of money in the economy, only a trade surplus or a large amount of foreign investment would.

Some have discussed a less restrictive version of this, using what’s known as a currency board: while still making the US dollar legal tender, a domestic currency would still be in circulation, with a near-unbreakable peg to the US dollar. While still not fully dollarizing the economy, it still restricts the ability of the Central Bank to print money enough that it would be considered a “second best” solution to eliminating the peso altogether.

In broad terms, dollarization is designed to eliminate the Central Bank's capacity to fund the government, which would be forced to finance the deficit permanently via more taxes, less spending, or more borrowing. Interst rates would therefore be set by global markets, as a sum of the relevant rates and of the country’s risk premium (aka the likelihood the government pulls any stupid stunts).

Would it work?

The million dollar question here is: would dollarizing the economy work? For reducing inflation immediately, yes. However, would that disinflation be sustainable? After all, fixing the exchange rate can always reduce price growth - but not indefinitely.

The main counterargument used against dollarization is that it eliminates the possibility of conducting countercyclical monetary policy: the Central Bank would be unable to lower interest rates during recessions or raise then during times of inflation. To be fair, yes, although to also be fair: when in Argentinian history has monetary policy be a solution rather than a problem?

Another issue is that, whichever currency you peg yourself to (the Brazilian real, the Euro, or a mix of various currencies) would have to go through a similar business cycle to prevent recessions or inflation from pouring into the country. Dollarizing might be an issue here, considering commodity prices are higher when monetary policy is tigther and vice versa, which might mean that Argentina endures balance of payments issues (a large chunk of our imports is just fuel) at the same time it has to raise interest rates.

Basically, historically, recessions happen (except in 2020) when there is some big imbalance that must be adjusted - and the quick adjustment often takes the economy down with it. There are three primary sources: monetary imbalances (i.e. printing a large amount of money and/or highly negative interest rates), external imbalances (a very overvalued real exchange rate), and/or fiscal imbalances (a very large deficit). Dollarization removes the first two sources of disruption altogether: because the Central Bank does not control the supply of money or the supply of hard currency, it cannot overstimulate the economy with one (or both) at the expense of a very large correction later.

However, the fiscal imbalances are not necessarily eliminated by dollarization. Whilst it does eliminate the possibility of paying for a colossal deficit by printing money, it still imposes no constraints on government spending and borrowing. And while the monetary policy rate is not set within the country, the rates for government bonds are - meaning that interest payments for the country’s debts could pass through into the private sector (aka the elusive “crowding out” effect).

Why is this a problem? Imagine the country continues to hold a large deficit while also not having control over the currency. Eventually, creditors would start getting antsy about the government’s ability to repay them - and they might all pull their money out of the country suddenly. To prevent this, spending would have to be slashed and taxes to be raised, while the risk premium increases, meaning monetary policy would become tighter. During good times, the opposite would happen. This means that monetary and fiscal policy would be procyclical and not countercyclical - aka that they would heighten, and not moderate, the business cycle, making recessions longer and more severe and expansions inflationary.

What if you fixed the fiscal imbalances? While I have Thoughts® about what they are, the issue is purely political: nobody either wants or has enough clout to get anyone else to agree to lose out from the current bloated level of spending and insufficient taxation, which is why nobody can fix inflation as of now. But if you solved the fiscal imbalances, would dollarization be feasible? Yes. But so would literally any single other solution to inflation, since independent monetary policy is easier to fix than political cowardice and opportunism. An inability to commit to fiscal adjustment means that dollarization is doomed, just like it means that literally every single other form of stabilization policy would also be doomed without it.

In fact, when Argentina tried “soft” dollarization in the 1990s (post in Spanish with a link to the English version at the top) (and a Currency Board with the gold standard in the 1890s) this is precisely what happened: undisciplined spending, due to provincial mismanagement and flawed reforms to social security, led to investors getting spooked after a bunch of financial crises in emerging markets. The fact that the economy was only partially dollarized made matters even worse because the exchange rate had become extremely overvalued and required even tighter monetary policy, while also making any changes to the parity nightmarishly recessionary.

Conclusion

So, is dollarization a good idea? Hardly. It’s become a fad among right leaning economists less because of its technical superiority to good old fashioned not acting like a crazed idiot, and more because of politically motivated wishful thinking. Inflation, especially of the magnitude and persistence Argentina has, is a hard nut to crack - and there isn’t a magical solution. If one simple trick existed, then it would have been implemented already. That it is so hard to solve is why it hasn’t been.

“When in Argentinian history has monetary policy be a solution rather than a problem?” - There definitely would be simpler ways to control and make the central bank more predictable to calm markets. I would be interested in understanding the mechanics of countries that have re-introduced a domestic currency. How irreversible would dollarization be? Also, to what degree would 🇦🇷 become a 🇺🇸 client state as a dollarized economy?