Chronicle of an Announced Death

From price controls to export bans, the authorities have it all wrong

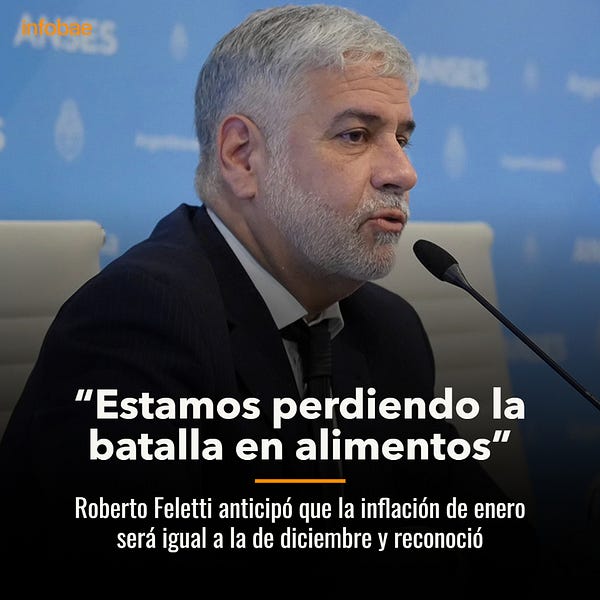

In a recent interview, Argentina’s Commerce Secretary Roberto Feletti made a bold announcement: the battle for inflation, particularly food, was being lost. He anticipated January’s inflation rate would be similar to December’s 3.8% MoM, although cited seasonal factors and mentioned that “new regulations” (which ones is left to the reader’s imagination) would reduce inflation by March. He also blamed the usual (false) suspects: “monopolists”, particularly in the supermarket business, “collusion” in the processed goods market (huh?), and “international inflation”. While I think all reasonable people saw this coming, I think it’s indicative of what the government’s inflation problem is: they don’t have any ideas for solving it, and what little they have wouldn’t be effective in principle.

The most clear-cut evidence that inflation is not under control is simply that it is high, remains high, and nobody expects it to decrease in the near future. Monthly core inflation has remained steadily in the 3.2% monthly range for six months and above 3% since October of 2020. Professional forecasts expect it to go even further, to 3.7%, in 2022 (with inflation being higher than in the previous year by December), and consumer’s inflation expectations have remained solidly anchored at 50% since February of 2021.

As many people, including myself, have previously said, price controls don’t really work in general and won’t work for Argentina specifically. The story of inflation isn’t especially complicated: there is too much money chasing too few goods. Sometimes there’s too few goods, but most of the time there’s too much money (it might be both, like in the 1970s).

For Latin America in general and Argentina particularly, it seems that the core of the story is even simpler, and has been for nearly 90 years: the government tells the Central Bank to pay for spending by creating money. Thus, the amount of money in the economy goes up - and generally, the amount of stuff doesn’t follow. Hence, the country’s disappointing history in terms of both growth (from one of the world’s richest countries in the early 1900s to poorer than most of its peers in the present) and in terms of inflation (average of 100% in the 20th century). Whenever the government ceased to rely on such mechanisms, and instead turned to the bond market, no meaningful reforms to spending (and rarely to taxes) were implemented, resulting in simply delaying inflation until the market’s demand for bonds was satisfied.

But that’s not what the government actually thinks, at least judging by its actions. So here’s where the government’s actual beliefs come into play: corporate greed, market concentration, and international prices are the core causes inflation. Neither of the three are correct.

Let’s start with corporate greed. Of course, I have long mocked the concept on Twitter, mentioning the “exogenous greed shock” required to explain inflation. Greed is not really an economic concept, and it’s not particularly clear what is ever meant by that, but generally it has to do with corporate profit margins. As my friend Joey Politano has previously explained, it might be true in a handful of cases that market concentration in the present has increased prices for some products in the US, but it’s not true that that dynamic has played out in the economy writ large. For Argentina, it’s normal to blame “greedy supermarkets” for this, but in fact the supermarket business has razor-thin margins (about 3%), so it’s not like they increasingly double their cut every month. In fact, most of the difference between prices at the producer level and prices at the store is explained by taxes and transportation costs.

Secondly, “corporate concentration” or whatever else. I’ve previously written about market concentration and inflation, and the topic is closely related to greed because more concentrated markets involve higher mark-ups. The main reason that this isn’t a factor in inflation is that the price level isn’t the same as price growth: the former is how expensive something is in absolute terms, the latter (inflation) is how much more/less expensive it’s getting. More market concentration would result in a higher price level, but not necessarily in faster price growth. You could make a case that concentration affects how companies set future prices, which in turn affects inflation, but then the real driver of inflation is expectations and not concentration. There is one sector, however, where prices have increased much faster than inflation due to a reduction in competition: textiles. So far since 2019, the textile industry has been benefitted by a massive ramp-up in trade protections, which has resulted in clothing and footwear outstripping the general price level almost every month.

Lastly, international prices. This is probably the hardest one to disentangle. The traditional case has been that the country “exports what it eats”, hence how when international commodity prices increase, so do local prices, boosting inflation. The trouble isn’t really that the logic is flawed, because it isn’t (and it was somewhat true in the 1960s and 70s, to some extent), but that the facts are just plain wrong. The country exports roughly as much meat as it does gold bullion - ergo, banning meat exports wouldn’t actually make much of a dent on inflation. Most of the country’s exports aren’t really linked to consumers, and most consumer goods aren’t just not food, but also not consumer products - the tradeables sector has long moved past the “meat and dairy” era (which was actually caused by stringent price controls domestically, but that’s neither here nor there). Most agricultural exports (either primary products or agricultural manufactures) are things that Chinese animals eat, not things that (Argentinian) people eat.

Because the diagnosis is fundamentally erroneous (besides brief flashes of lucidity that never seem to pan out), solutions are never quite right. Price controls, to quote Harold Demsetz, are like “breaking a thermometer to change the weather” - the Argentinian government, despite systematic proof that they barely work, frequently implements them as a way to simply make the CPI lower by specifically targeting the surveyed products. Export bans actually make inflation worse, because the US dollar acts as a proxy for inflation expectations, and a balance of payments crisis is probably not a way to stabilize outlooks. Regulations on how supermarkets can display products, how many slots on a shelf a single brand can take up, or how much rents can increase don’t seem to actually change anything.

Instead of false solutions that don’t address any issues we actually have, the authorities should fix the core underlying issues: monetary financing of an excessively large deficit. The recent agreement with the IMF kind of tries this by promising a reduction of the deficit and more bond market financing, but nobody actually believes the government is going to try to buckle its belt and instead has promised to reduce the deficit through “growth and tax compliance” - unsurprisingly unlikely (here’s a good read on this, in Spanish). And it’s not very plausible that the populist left would end up cutting spending, for ideological reasons, plus because the agreement stipulates increases to investment and constant “social spending”, so the only solution is to raise taxes. Since taxes on individuals have been cut significantly recently, the only options are highly distortionary taxes like on exports or bank deposits, and on corporations - particularly unwise since they already face total tax rates of over 100% of profits (per the World Bank). The main remaining item to cut is energy subsidies, which I’ve advocated for, but which would at least temporarily raise headline inflation. It’s even possible that the deficit might increase if inflation remains constant or even decreases, since a large chunk of spending (pensions and welfare) is adjusted to past inflation, which would put an even bigger strain on the promises made.

Monetarily, it’s not 100% clear if the authorities can deliver on their promise to replace seigniorage with debt, since most of it would be inflation-linked and/or dollar-linked, potentially creating unsustainable feedback loops between backwards-indexed spending items and inflation-linked bonds. The “unpleasant arithmetic” derived from an inflexible deficit and limited demand for government bonds is still alive and well. Additionally, we have promised the IMF real positive interest rates, but the authorities have been singing the praises of positive rates since taking office and yet rates have not been greater than inflation for a single day in three years.

Sources

My posts on price controls, the export ban on meat, and competition and inflation

Joey Politano’s post on corporate profit margins and inflation

Becker-Friedman Institute, “The Monetary and Fiscal History of Latin America”

Sargent & Wallace (1981), “Some Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic”

Gerchunoff (2006), “Requiem para el stop and go... ...¿Requiem para el stop and go?” (in Spanish)

Andrés Borenstein, “El diablo estará en los detalles”, Revista Seúl, 2022 (in Spanish)

In many countries that experienced high inflation, politicians were able to give independent central banks a mandate to reduce inflation. Voters were surprisingly supportive, even when getting inflation under control was painful. What makes Argentina different?

The ancient history of price controls is concrete proof they don´t work. This provides a picturesque view of price controls in Brazil: Note that while the first is “effective” for a few months, subsequent ones lose “effectiveness” very quickly. In addition, inflation rebounds more strongly after each try!

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/how-can-you-talk-coherently-about