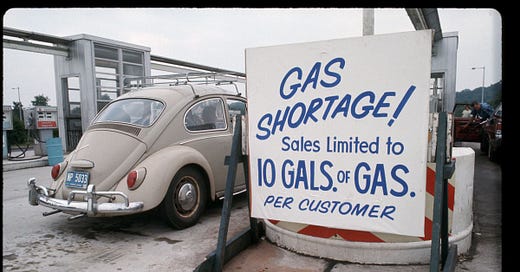

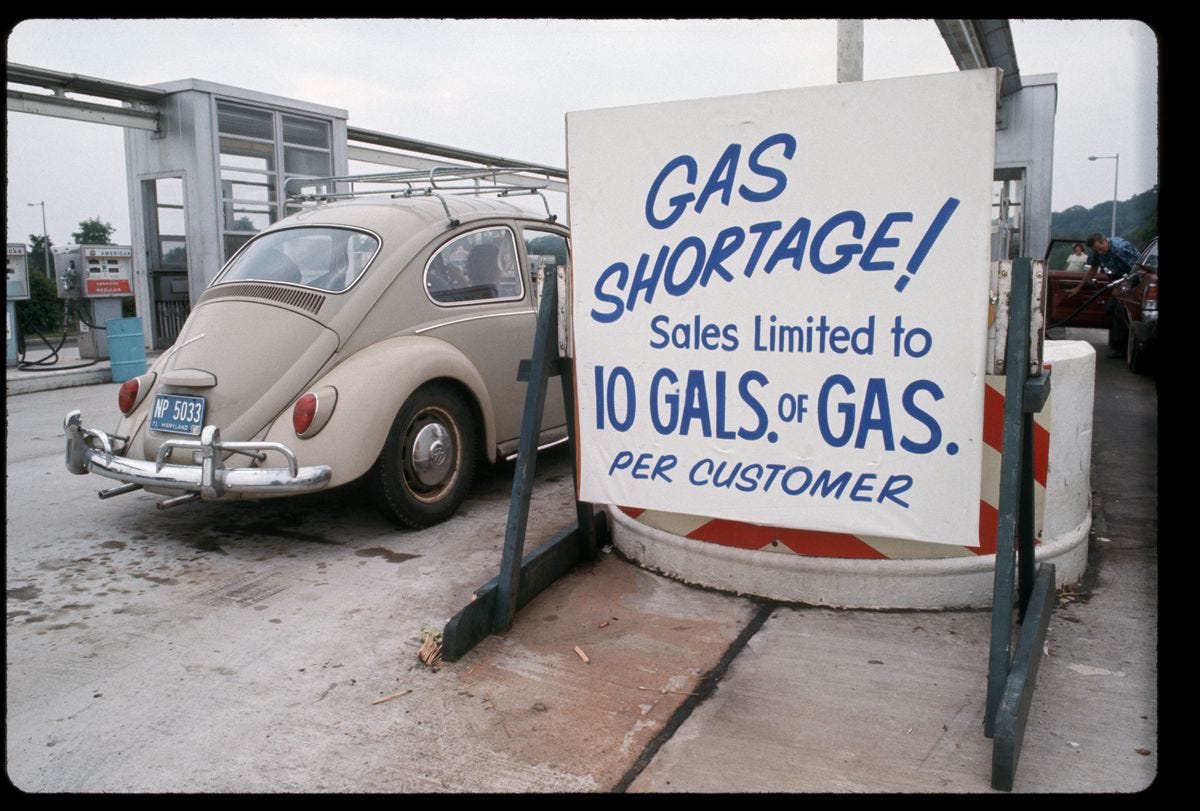

On October 19, 1973, immediately following President Nixon’s request for Congress to make available $2.2 billion in emergency aid to Israel for the conflict known as the Yom Kippur War, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) instituted an oil embargo on the United States. The embargo ceased US oil imports from participating OAPEC nations, and began a series of production cuts that altered the world price of oil. These cuts nearly quadrupled the price of oil from $2.90 a barrel before the embargo to $11.65 a barrel in January 1974. In March 1974, amid disagreements within OAPEC on how long to continue the punishment, the embargo was officially lifted. The higher oil prices, on the other hand, remained.

As Arthur Burns, the chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time, explained in 1974, the “manipulation of oil prices and supplies by the oil-exporting countries came at a most inopportune time for the United States. In the middle of 1973, wholesale prices of industrial commodities were already rising at an annual rate of more than 10 per cent; our industrial plant was operating at virtually full capacity; and many major industrial materials were in extremely short supply”. (…)

From the vantage point of policymakers in the Federal Reserve, the 1973-74 oil crisis served to further complicate the macroeconomic environment, particularly in regard to inflation. Fed Chairman Burns argued in 1979 that the inflation appeared to be the result of a plethora of forces: “the loose financing of the war in Vietnam. . .the devaluations of the dollar in 1971 and 1973, the worldwide economic boom of 1972-73, the crop failures and resulting surge in world food prices in 1974-75, and the extraordinary increases in oil prices and the sharp deceleration of productivity.

Michael Corbett “Oil Shock of 1973–74”, Federal Reserve History

The basic facts

Inflation was really high in the 1970s, and was slightly too high going back to the late 1960s even. The proximate causes were an oil embargo by a cartel of Arab oil producers that led to the price of oil quadrupling, plus a bunch of other commodity price increases (minerals, crops, etc). However, the economy was already in a weak state, so it couldn’t take those increases and inflation got out of control - even if unemployment was relatively high.

The inflation later ended, in the early 80s and early 70s. Exactly why it happened is the source of a somewhat contentious debate, but the generally accepted explanation is that Fed Chairman Paul Volcker raised interest rates by a lot (sometimes even above 20%), which drove the economy into a recession but decreased inflation significantly.

The key thing to understant here is that there’s a trade-off between inflation and unemployment. When unemployment is high, there’s lots of slack in the economy, because people are generally doing badly - so prices don’t increase that much. However, if unemployment gets really low, then people are able to bid up on things they want, and if companies want to respond by producing more they have to hike up wages to peel away workers from their competitors. This negative relation is known as the Phillips Curve, after the economist who originally discovered it. The problem, in the 70s, was that unemployment and inflation were high, which wasn’t really something you could expect.

Importantly, this means that unemployment can get “too low” - i.e. that at some point the labor market is so tight that workers demand very high raises to change jobs, so prices increase in response, which results in the real wages of workers not increasing as much as they wanted, so they demand more raises, and so on and so forth. The logical conclusion is that, when unemployment is in “too low” territory, the economy might be too “hot”, so it needs to be cooled down. This “equilibrium” rate of unemployment is known as the natural rate, and is usually associated with the concept of the NAIRU - the Non Accelerating Inflation Unemployment Rate (self explanatory).

The Phillips Curve was later “augmented” to include inflation expectations, i.e. what people think future inflation will be. This means that maybe everything is fine enough, but the economy is getting close to the low unemployment - high inflation point, then people might start expecting inflation to go up, so they start demanding the raises and hiking prices in advance, which turns inflation expectations into self-fullfilling prophecies.

Asleep at the wheel

A very standard explanation of the Great Inflation is this: the Federal Reserve didn’t think it could do anything about inflation, so it did nothing - and inflation got out of hand. A Fed economist said in 1971:

The question is whether monetary policy could or should do anything to combat a persisting residual rate of inflation ... The answer, I think, is negative. ... It seems to me that we should regard continuing cost increases as a structural problem not amenable to macro-economic measures.

Basically, the issue at hand was that the people running the economy didn’t really think they could keep inflation under control, or wouldn’t act to do so. There is actually some degree of merit to this poisition; in 2004, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke said (in a talk about oil and the economy):

How then should monetary policy react? Unfortunately, monetary policy cannot offset the recessionary and inflationary effects of increased oil prices at the same time. If the central bank lowers interest rates in an effort to stimulate growth, it risks adding to inflationary pressure; but if it raises rates enough to choke off the inflationary effect of the increase in oil prices, it may exacerbate the slowdown in economic growth. (…) Because these two factors tend to pull policy in opposite directions, however, whether monetary policy eases or tightens following an increase in energy prices ultimately depends on how policymakers balance the risks they perceive to their employment and price-stability objectives.

Bernanke later makes the case that the balance ends up being a finely tuned analysis of the initial state of the economy, but it probably amounts to some extent to a gut call - does inflation that is ever so slightly too high matter more or less than unemployment that is ever so slightly too high? There aren’t easy answers! Reasonable or not, economists in the 70s decided that unemployment was a much bigger deal than inflation, so they generally ignored it.

A major reason for this belief was the experience of the Great Depression: most prominent economists had been alive back then, many as adults, and remembered how bad it was. As a result, they didn’t want to risk a second coming of it by intentionally raising unemployment to control inflation. And politicians were more than happy to encourage them not to, given that a bad economy gets them booted from office. Most egregiously of all, Richard Nixon frequently lobbied Arthur Burns into not raising interest rates, at one point even threatening to replace him if he did.

Because everyone thought that the Fed wouldn’t do anything about inflation, inflation expectations started rising - so people prepared for higher prices by demanding higher wages and raising prices in anticipation for their money being worth less in the forseeable future. Not only that, but many workers had inflation adjustments in their contracts, so they often didn’t even have to ask for raises at all. The Fed so complacent about inflation in the early 70s meant that nobody trusted in them when it got really bad just a handful of years later.

Consequently, Paul Volcker had to be extra hard on inflation - in the words of a Reagan advisor, he had to prove that he was willing to “spill blood, lots of blood, other people’s blood” to keep inflation in check. Had Arthur Burns (or his even less competent successor, William Miller) done much less about inflation earlier, policies as radical as the Volcker Shock wouldn’t have even been necessary. Volcker himself later said in his memoir:

Did I realize at the time how high interest rates might go before we could claim success? No. From today’s vantage point, was there a better path? Not to my knowledge — not then or now.

The gist of the mainstream explanation of the Great Inflation is this: the economy was running very hot, due to a tight labor market and high government spending on the Vietnam War - which, being a quagmire, had no foreseeable ending in sight - and it was badly prepared for a shock like the oil embargo, plus some price control shenanigans, plus the end of the gold standard.

Since policymakers and academic economists had the wrong ideas about the economy, they picked policies that wouldn’t sacrifice growth in favor of disinflation, which resulted in inflation getting out of hand and having to sacrifice a lot of growth to actually contain it down the line. And because nobody believed the Fed would “take away the punch bowl”, so to speak, then the only workable solution was a radical program like the Volcker Shock.

How little we know

But why were economists so wrong about the economy? There was another problem in the 70s: economists back then didn’t know all that much about the economy. Pretty sad state of affairs, really.

In the 50s, economists had crude but roughly correct ideas about the economy: inflation happened when aggregate demand was above capacity, and there wasn’t really a trade-off between inflation and unemployment as a “make one higher the other one goes down” relation like it would be treated later, but more as a combination of fundamental economic dynamics. But later, the generally sound policy ideas of the 50s were replaced by overly optimistic beliefs about how low the natural rate of unemployment was, and that inflation was incredibily insensitive to economic slack.

This meant that the Fed simply didn’t see a problem with the things it was doing until inflation got out of hand. This also applies to why the Fed didn’t actually try to counteract fiscal expansion: it didn’t think it had to. Given that most economic advisors are professional economists (well, except William Miller, who was a CEO), the wrong ideas about slack in the Treasury were the same wrong ideas about slack in the Fed.

Let’s go into this very dry, technical issue in some detail. What exactly were professional economists wrong about?

Firstly, they were shockingly bad at estimating the output gap. The output gap is the distance between the economy and full utilization of factors, meaning that factories are running at full steam and the labor market is as tight as it can be. This also ties with their frequent lowballing of the natural rate of unemployment, and some seemingly unsound assumptions about the strength of the Phillips Curve relationship. And that’s why nobody realized the economy was too hot right before the oil embargo: they the numbers they used said it wasn’t.

Plus, the models economists back then used weren’t, to put it gently, very good. Models back then made all sorts of eyeroll-worthy assumptions, and weren’t especially good at explaining how prices and wages were set. Even the most sophisticated and advanced models simply relied on guesswork to explain how markets set prices. From Blanchard (2000):

But, as the early models were improved in many dimensions, the treatment of [market] imperfections remained surprisingly casual. The most obvious example was the treatment of wage adjustment in the labor market. In early models, the assumption was typically that the nominal wage was fixed, and that the demand for labor then determined the outcome. Later on, these assumptions were replaced by a Phillips curve specification, linking inflation to unemployment. But there was surprisingly little work on what exactly laid behind the Phillips curve, why and how wages were set this way, why there was little apparent relation between real wages and the level of employment. As a result, most macro models developed in the 1960s and 1970s had a schizophrenic feeling: A careful modeling of consumption, investment, and asset demand decisions on the one hand, an a-theoretical specification of price and wage setting on the other. (…)

So, to make progress, one had to think hard about market structure, and who the price setters were. But such focus on market structure, and on imperfections more generally, was altogether absent from macroeconomics at the time.

Simply put, they didn’t think very carefully about prices and wages, mostly by not using enough microeconomics in their macroeconomics. Plus, economists just didn’t pay too much attention to a number of questions. The economy changed a lot during the 70s, and it caught them with their pants down. From Tobin (1980):

We macroeconomists were caught unawares. It was not simply that our models, theoretical and econometric, now had to be applied to novel situations. Worse than that, the shocks of the 1970s required some fundamental rethinking and rebuilding. From an American perspective, the main events were of three kinds: the increased openness of the U.S. economy and the integration of U.S. financial markets with those overseas, the scrapping of the Bretton Woods system of adjustable exchange parities and its replacement by a regime of marketdetermined exchange rates with largely uncoordinated national interventions, and the predominance of price, supply, and demand shocks from sources other than government policies and the domestic industrial economy

In a nutshell, traditional models were mostly about the domestic non-agricultural goods producing sector, not about foreign oil cartels. This was compounded by changes in how international trade and currencies worked and behaved. And finally, and most interestingly, the inflation had a variety of supply-side impacts economists ignored; the economy had high unemployment and inflation because investment wasn’t high enough to return to capacity.

For what it’s worth, the 1960s and 1970s economists were pretty much right about the Phillips Curve being pretty flat - which meant that there wasn’t as hard a tradeoff between inflation and unemployment as some thought (meaning that going from 4% unemployment to 2% wouldn’t raise inflation very much). Per acclaimed contemporary macroeconomist Jon Steinsson:

Whether you look at the 1980s expansion, the 1990s expansion, or the 2010s expansion, the unemployment rate, if you just plot it, it just keeps falling. It keeps falling and falling and falling and it never levels out. Maybe at some point it would, but one view of that is that we’ve just never gotten to the point where we have true full employment.

Regardless, 70s economists did get wrong how costly (in terms of aggregate wellbeing) inflation, especially coupled when stagnation, was, so their belief that sliding on the Phillips Curve from low unemployment to even lower unemployment wouldn’t be painful was plain wrong.

Avenue Q

There is a third explanation. Back in the 60s and 70s the economy, and particularly the financial sector, was very extensively regulated. One of such regulations was Regulation Q. What Regulation Q did was pretty simple: cap the interest rates at which banks could pay for deposits at 4%.

Until 1965, the Fed funds rate (the benchmark interest rate) was lower than 4%, so there wasn’t much harm from it. After 1965, the Fed rate exceeded 4% - meaning that people with money in the bank lost out compared to other investment options, and pulled their money out. Additionally, inflation started being higher than 4% later on, which meant that the real interest rate became actually negative - the money you deposited was worth less after you took it out of the bank.

Since banks need deposits to be able to lend money, credit shrank significantly, which had negative consequences on output and employment. Plus, the money being taken out was actually being spent, and since banks couldn’t lend, companies couldn’t increase production, so inflation raged on. Regulation Q was repealed in 1980, and the economy improved afterwards.

The Regulation Q story is somewhat convincing: it matches the timing pretty well, and has a solid enough logic behind it. However, plenty of other countries had high inflation in the 70s, and barely any of them had similar caps on interest rates - in fact Germany, which did have a Q-esque rule, actually scrapped it in 1965.

Plus, this is just a very crude monetarist explanation. “Interest rates for savers were low so the Federal Reserve had to raise them, because otherwise inflation would keep growing” is like the Milton Friedman 101 explanation of inflation. That interest rates can manage aggregate demand and that unattractive rates can lead to it far outstripping demand isn’t very revolutionary, it’s just a consensus view.

The second eye on the prize

What if inflation wasn’t caused by these galaxy-brained problems, but rather by something much simpler: important prices going up. Oil is used for many things, people consume a lot of it, and many things are moved around by trucks. And it wasn’t just oil: the prices of wheat spiked due to a drought in the USSR, and the prices of minerals, lumber, and many other products soared at different times in the 70s.

This version of stories divides the Great Inflation in two: one in the early 70s, one in the late 70s - both simultaneous oil and food price shocks. The first one was also paired with the end of Richard Nixon’s price controls, aiming at reducing the previous nascent inflation. Naturally, lifting price controls means that demand grows a lot very quickly, so companies can’t respond to it fast enough and raise prices to match demand.

And all of these things didn’t just drive up costs: they also slowed down output. Plus, investments in things like mines or oil wells take a while to get off the ground. Meanwhile, you had a full economy where everyone was bidding up the prices of various goods. And finally, population had exploded in the 50s and 60s, leading to the famous “baby boom” and higher than ever demand for basically everything.

Moreover, the Fed hiking rates very aggressively only prolonged the inflation, because it made the shortages of goods much more pronounced. Plus, mortgage payments were also included in inflation measurements until 1983, which meant that by raising rates the Fed was actually raising inflation as well. In fact, inflation was lifted 2.5%, roughly, just by this factor in 1979 and 1980 - the initial years of the Volcker Shock.

Another reason why inflation increased so much was because, if demand is really high, costs are up, and wages can’t be cut, then something has to give - prices. The way to keep companies in business, given higher costs, was to reduce the real aggregate wage, and because labor was far stronger then than it is now, it would have to be done primarily by cutting real wages rather than just firing people.

Plus, oil getting more expensive reduced real wages a lot, because people also spend a lot of money on energy-related products, which made the recession worse. And inflation meant that people made “more money” and were taxed more, since tax brackets weren’t updated. This meant that potential output (the one determined by investment) went down a lot, but actual output went down even more. And investments were actually “too low” to mature quickly enough, because oil prices were volatile and the economy was too big a mess to plan ahead - both worsening unemployment but also prolonging shortages.

Furthermore, higher oil costs made keeping the same capital goods (machines, vehicles, etc used by employers) too costly, so they were scrapped faster than ever. This also meant that workers were less profuctive, because the things they used to work were less effective. But because nobody noticed fast enough, then wages were set at excessively high levels, resulting in shrinking labor demand and a higher equilibrium rate of unemployment.

So the explanation here isn’t that expectations, or bad economic beliefs, or obscure regulations drove up prices - it was a shortage of things paired with substantially higher demand for them. The inflation ended in the late 70s when all the investments paid off and the droughts ended, so there weren’t any more shortages.

The solution, in this view, wouldn’t have been aggressive monetary policy and fiscal restraint, but rather a much more hard to parse agenda of incomes policies. Incomes policy is an extremely vague and nebulous term (even its proponents back in the 70s grant that), but in general, it would have proposed to cut inflation by an ambitious combination of price and wage controls, pro-competition reforms, labor law reforms, and targeted rationing of credit and spending towards sectors of the eocnomy that were suffering from such shortages. From Tobin (1980):

This combination of controls and demand management would avoid the major pitfalls that have discredited previous episodes of controls. It would not try to restrain wages and prices in face of excess demand. At a macroeconomic level, this would be avoided by the consistent scheduling of monetary disinflation and guideposts. At a microeconomic level, compliance with guideposts would be induced by tax-based rewards and penalties, leaving individual firms flexibility to respond to the circumstances of particular markets. At the time the policy was ended, there would be no reason for anyone to be committed to or to expect wage or price increases greater than the final guideposts. Macroeconomic demand policy would be consistent with the actual inflation rate at the time.

It’s a lot to chew! And I am skeptical. For one, the fundamental problem of “economists not understanding the economy very well” remains, and was especially pronounced for the supply side of the economy. To quote Paul Samuelson “God gave the economist two eyes. One for supply and one for demand”. So it’s possible an ambitious incomes policy program would have worked, but it’s also possible it turned into a bottomless pit of government spending that only fueled more and more inflation (the Argentina kind of incomes policy). And even subtracting the big shocks from inflation, the US still had a substantially higher level of inflation starting in 1965 - one that matches to some degree the problems outlined before.

Conclusion

The story of the Great Inflation is very complicated, and it’s very likely that the four explanations listed above (which are at least the most common ones) all play their part. Specifically important prices going up created a whole host of economic disfuncions in an economy that was already saddled by bad policies (such as an overly accommodating monetary policy, the Vietnam War, Regulation Q, etcetera) and with a Central Bank that wasn’t all that willing to do its job properly to an extent that people didn’t trust it. In this economy, output doesn’t grow, investment is too weak, unemployment is stubbornly high, and prices still grow too much. It’s probable that some well-targeted incomes policy coupled with a monetary stabilization plan would have worked, so the human costs of disinflation were much lower.

The most obvious comparison today is the economic recovery of the United States and the recent flareup in inflation. For once, people actually trust the Federal Reserve, and there isn’t a ridiculous cap on returns to deposits, so no worries. And economists are somewhat better at their jobs (one would hope), so the problems of missing all the red flags until you’re knee deep in something unpleasant seems unlikely.

Plus, the economy is nowhere near full capacity - it has returned to pre-pandemic levels but those missed quarters of growth are still pending. And the labor market has made an even less complete recovery, with lower participation, lower employment, and higher unemployment than before the pandemic.

And finally, there actually are a variety of supply-side constraints, most notably in housing and in manufacturing. The former, as I have previously touched upon, is simply “milennials entering the housing market” and “wealthier people having a bunch of money saved from COVID” coupled with “the United States has far too few homes”. The latter generally has to do with a worldwide shortage of semiconductors, due to tensions with China, a surge in demand (somewhat linked with cryptocurrency, of all places) and a massive fire in one of the world’s largest producers of such equipment.

Sources

The basic facts

Michael Corbett, “Oil Shock of 1973–74”, Federal Reserve History

Michael Bryan, “The Great Inflation,” Federal Reserve History

Dylan Matthews, “Don’t worry about inflation”, Vox (2021)

Matt Ygglesias, “The NAIRU, explained”, Vox (2014).

Ben Bernanke, “Oil and the Economy”, Speech at Darton College (2004)

Asleep at the wheel

DeLong (1997), “America's Only Peacetime Inflation: The 1970s”

Nelson (2004), “The Great Inflation of the Seventies: What Really Happened?”

Romer (2005), “Commentary on "Origins of the Great Inflation"

How little we know

Tobin (1980), “Stabilization Policy Ten Years After”

Blanchard (2000), “What do we know about Macroeconomics that Fisher and Wicksell did not?”

Woodford (1999), “Revolution and Evolution in Twentieth-Century Macroeconomics”

Romer & Romer (2002), “The Evolution of Economic Understanding and Postwar Stabilization Policy”

Regulation Q

Drechsler, Savov, & Schnabi, “What really drives inflation”, VoxEU (2020)

The supply-side

Klein (1978), “The Supply Side”

Blinder & Rudd (2013), “The Supply-Shock Explanation of the Great Stagflation Revisited”

A shorter, compact view of the Great Inflation

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/08/25/the-origins-of-the-great-inflation/