… the tightness has completely disappeared, and been replaced by unbelievable pain

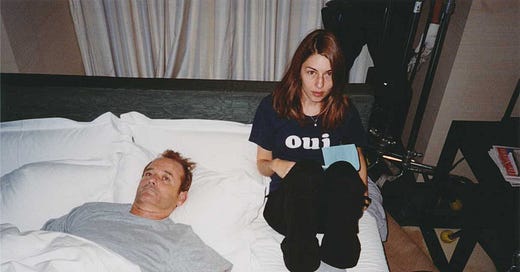

Bob Harris in Lost In Translation (2003)

Lost in Translation by Sofia Coppola is a movie I don’t especially like (I’m a big fan of hers TBF), for not especially clear reasons. But regardless, the movie follows two characters who, at different ages (their early-to-mid twenties and their 50s) are dealing with a sort of quiet crisis, a vague sense that everything is going wrong.

I rewatched it a few weeks back because I got Sofia Coppola’s book as a present from my girlfriend, and because this isn’t a film studies blog, something that surprised me was how similar the main characters’ predicament was to Japan’s longstanding economic issues. So, what’s wrong with Japan?

Boom and bust

During the second half-ish of the 20th century, Japan experienced what has been called an “economic miracle”: rapid economic growth that made the nation go from being devastated by American actions during World War Two, to the planet’s second largest economy. Behind this transformation, was an impressive corporate culture, government industrial policy agenda, educated population, and investment, in both new technologies and new businesses. In fact, by the 1980s Japan was so economically vibrant that it was considered a serious competitor to global US hegemony, which resulted in widespread cultural hysteria in the United States.

However, everything changed in the early 1990s, for a simple reason: Japanese asset prices soared, especially land prices, which was associated with both the strong economy and with loose monetary policy, but also contained some element of “speculation” or “mania” (see more about financial markets here). Fearing an overheating economy, the Bank of Japan drastically tightened policy, which showed up in broadly-defined monetary aggregates nearly instantly. The collapse in asset prices, especially land (which was used as collateral for most businesses) dragged the entire economy into a severe depression.

The issue isn’t that this was bad (it was), but rather, that the Japanese economy didn’t grow again in the 1990s. From 1991 to 1999, the economy grew barely 1% a year, compared to 4% in the previous decade - and GDP oscillated between 4% and 6% below its potential level. Inflation was also vanishingly low, with the Japanese economy often slipping into deflation. What happened? Much was written about it, with the previously praised elements of Japanese economic policy and corporate culture being trashed: industrial policy promoted inefficiency; the Shūshin koyō, a “class” of loyal long-tenured employees, were a source and symptom of low dynamism; the keiretsu, large networks of conglomerates, banks, and suppliers, reduced competition; the corporate decisionmaking that prized consensus and unanimity was stifling. Also noted was the small size of Japan’s businesses, the lack of low-skilled labor that raised fix costs, and the slow uptake in computerization. Additionally, the high debt burdens of Japanese businesses and banks were noted, poitning so astonishingly high debt-to-GDP ratios.

The main diagnoses, thus, were that Japan’s economic issues were supply-side: first, problems with its business sector, to which the strikingly fast (though, now, not unusual) aging and drop in fertility was added as the Lost Decade became the Lost Twenty Years and then the Lost Thirty Years.

The cross of gold

Paul Krugman, however, had a different idea: Japan’s economic situation was caused by a lack of demand, not of supply. Krugman’s case for Japan’s issues being demand-induced comes from a (then) obscure Keynesian concept: the liquidity trap.

Coined by Keynes himself, the idea was that there was a certain point where the demand for money is so high that any injections of liquidity get instantly saved. This phenomenon pushes interest rates to zero, at which point monetary policy is rendered completely useless. The logic is that government bonds and money become perfect substitutes, which fixes interest rates because all additional money goes directly into savings. This is why Japan had such high savings rates, and why the debt-to-GDP level was so high: people just demanded more Japanese debt.

The traditional Keynesian response to the liquidity trap was expansionary fiscal policy: more government spending, and tax cuts. However, the high debt-to-GDP levels may have been an issue to consider. However, the major question regarding fiscal policy is that, once again, monetary demand is very high, meaning that there is no gurantee that stimulus checks don’t get saved away either - especially when the fiscal multiplier isn’t very large in general.

In this economy, savings are consistently high and investment is consistently low, which results in low spending and overall stagnation. Additionally, since nobody is spending, and the economy is stalling, businesses respond by cutting prices - deflation. Any potential stimulus gets saved away: any alternative monetary programs simply result in more bonds being purchased (or higher bank deposits), while fiscal stimulus just fattens up retirement and savings accounts.

So what’s the solution, if monetary policy is useless and fiscal policy is also useless? Well, those two are useless given the current rules of the economy. But what if you changed the rules? The general rules of how the economy, in particular regarding the business cycle, works are generally assumed to be set by the Central Bank - hence the vibecession - and the Bank of Japan was simply too trustworthy.

There is also a core misunderstanding at play: monetary policy is not the same as interest rates. Interest rates can be low and still not be stimulative, for the very simple reason that economic decisions are made including future expectations, and not just past conditions. The problem with the Bank of Japan was that, in quashing the 80s boom to control asset prices (which it iself caused), it established itself as being very aggressive with regards to inflation. This means that if consumers and businesses expect that the economy will become “hot” again, then they might fear that the Bank of Japan could cut the expansion short in order to preserve the stability of the yen. The key to the liquidity trap is not the demand for money, but rather, the credibility of the Central Bank - that its promises were too credible. Bank of Japan, You Smoke Too Tough. Your Inflation Target Too Low. Your Bitch Is Too Bad. They’ll Liquidity Trap You.

To quote Krugman again:

… there is in principle a simple, if unsettling, solution: What Japan needs to do is promise borrowers that there will be inflation in the future! If it can do that, then the effective "real" interest rate on borrowing will be negative: Borrowers will expect to repay less in real terms than the amount they borrow. As a result they will be willing to spend more, which is what Japan needs.

(…) The trouble--the other half of the Japanese trap--is that while the conclusion that Japan needs inflation emerges from what looks like impeccable economic logic, we live in an era in which central bankers believe (and are believed to believe) in price stability as an overriding goal. The peculiar result of the credibility of modern central bankers as inflation hawks is that no matter how much money the Bank of Japan prints now, it doesn't matter: It can't lower the nominal interest rate, because that rate is already zero, and because people don't believe that it will allow inflation to break out any time in the future, it can't lower the real interest rate either.

The biggest example of a liquidity trap in history is, of course, the Great Depression. Or Argentina’s 1990s crisis, which was similar in dynamics and the subject of a rare Spanish language post. The United States used the gold standard as a way to shore up credibility; in the words of Herbert Hoover “We have gold because we cannot trust governments”. The issue was that the gold standard severely constrained monetary policy, to the point where the Federal Reserve was completely incapable of stimulating the economy (for a variety of complicated factors).

Even though the Japanese Lost Decade(s) wasn’t as severe, fundamentally it was the same issue. What was the solution?

Letting loose

The comparison to the Great Depression, thus, helps point to a solution, even though the Japanese Lost Decade(s) wasn’t as severe, since fundamentally it was the same issue.

So how did the Depression end? The conventional wisdom that the New Deal ended the Depression is wrong. The stimulus, according to Paul Krugman, was 3% of GDP—impressive, but dwarfed by the 25% of GDP the US did last year, or by the fact that actual GDP was 42% lower than potential GDP. In reality, what happened was that the United States went off the gold standard - and what triggered the economic recovery wasn’t actually going off gold, but simply announcing it. And not just that, but in an aggressive and rapid manner, i.e. showing “Rooseveltian resolve”. The solution, the liquidity trap literature says, is for Central Bankers to promise to be irresponsible, i.e., to commit to letting inflation run wild for a little bit. There are many ways of doing this, but the key is to allow inflation to be higher than “tolerable” for some period of time, in order to “catch up”, nominally speaking.

Was this tried in Japan? Yes, actually. When the (late) Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe returned to politics in 2012, he promised an economic program centered on “three arrows”: expansive monetary policy, flexible fiscal policy, and, structural reform. This combination, known as Abenomics, was partially successful: growth was revived and inflation increased, though not long-term inflation expectations. Japan had modest, but steady, growth and modest, but positive, inflation, plus some structural reforms. There were also other challenges (such as extremely low female labor force participation) but fundamentally monetary policy didn’t go far enough in its “irresponsibility” during the Abenomics Era.

The last chapter is actually currently unfolding. Like everyone else, Japan did a big stimulus program during 2020, and like everyone else, it had a big bout of inflation in 2021 (reaching an unprecedented, absurdlly high “2%”). However, unlike everyone else, the reaction of the Bank of Japan was to simply do absolutely nothing: the monetary policy rate has remained flat at -0.1% since 2016. It is expected to tighten in April 2024 (let’s not get ahead of ourselves here) but the idea was that it would cause large wage hikes in the December 2023 shunto negotiations (i.e. sectoral wage agreements), which has been the case, with the largest pay increases since 1992.

Conclusion

So, Central Banks shouldn’t be hardasses because that’s bad for the economy too.

um... maybe a really big war had something to do with ending the depression as well...

Muy claro, gracias. Btw: la explicacion de la crisis argentina 2001 como trampa de liquidez no la habia escuchado, es buenisima tambien