Why did the Great Depression happen?

"If you want to understand geology, study earthquakes. If you want to understand economics, study the biggest calamity to hit the U.S. and world economies." - Ben Bernanke

Let me end my talk by abusing slightly my status as an official representative of the Federal Reserve. I would like to say to Milton [Friedman] and Anna [Schwartz]: Regarding the Great Depression. You're right, we did it. We're very sorry. But thanks to you, we won't do it again.

Ben Bernanke, “On Milton Friedman’s 90th Birthday”, 2002

The Great Depression is the most famous recession of all time, and practically synonymous with “bad economic outcome” these days. It’s probably the worst recession in modern history, at least for the US. But it’s also incredibly poorly understood, in ways that are damaging to understanding of economic phenomena.

Monday, Monday, stocks going down on Monday

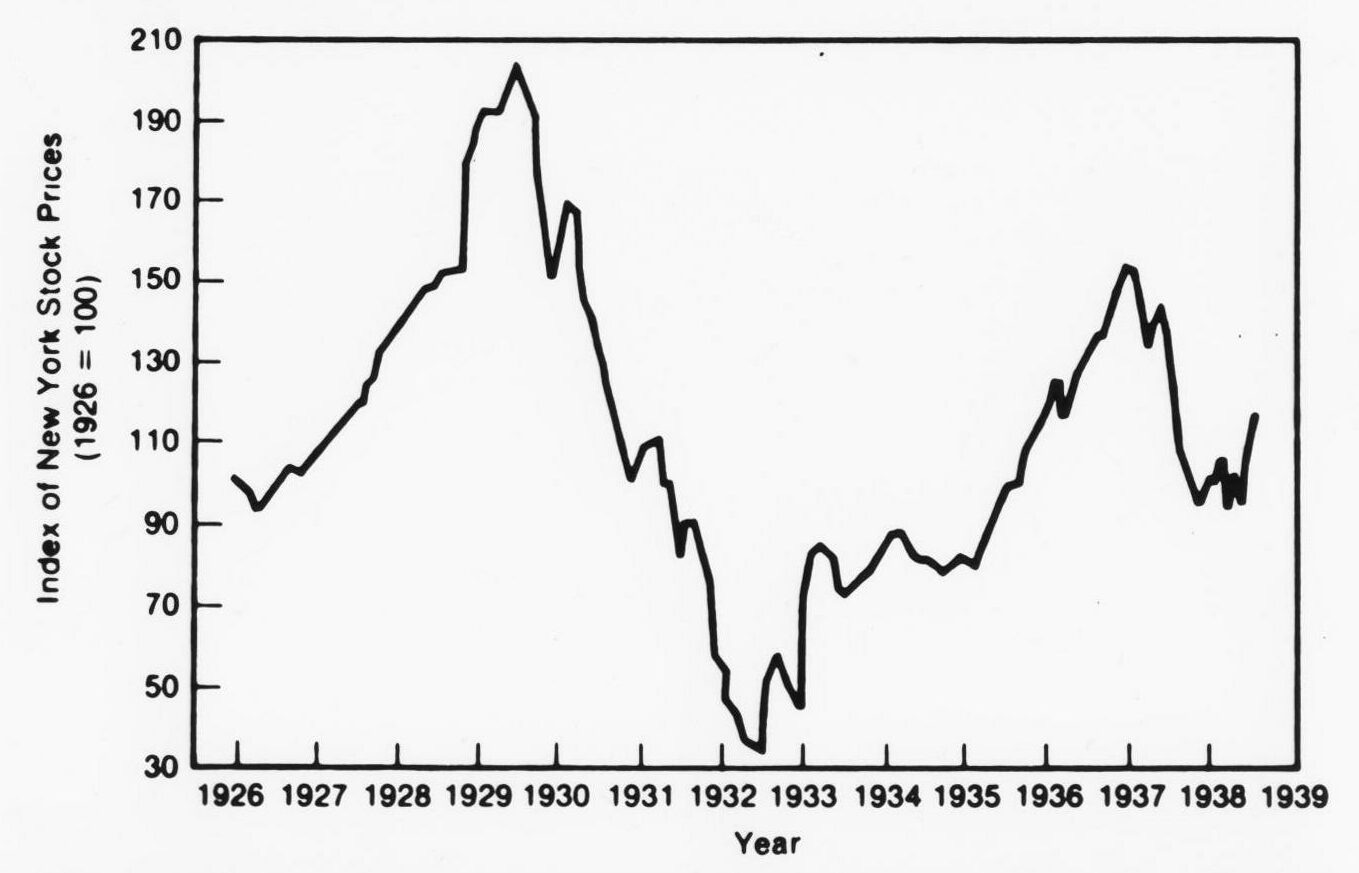

A very common view is that the stock market crash of 1929 and the Great Depression were the same event; stock prices declined sharply in 1929, falling 13% in just one day (October 28, 1929 - known as “Black Monday”) and by nearly half in a handful of weeks, but the Depression itself was a prolonged recession that lasted from 1929 to 1933 - and saw real GDP drop by almost a third and unemployment spike to nearly a quarter of the population.

The economy of the 1920s was somewhat strong - they are known as the “Roaring Twenties” for a reason. Investment in factories, buildings, and other productive endeavors surged, and production of commodities matched it. New technologies abounded and spending on new goods was plentiful. As output and national wealth grew, although not equitably, a series of investment bubbles started forming - people put too much money into the stock market and companies were trading too highly versus their “real” value.

The Federal Reserve decided that this bubble could cause significant instability in the economy, and decided to “pop” it by raising interest rates. Now, there’s two problems with this approach. The first is that it’s basically impossible to identify a bubble - maybe investors weren’t betting on the present value of companies, but on their potential for growth (not unbelievable, given the vibrance of the 20s as a whole). This would mean that there wasn’t an asset price bubble, just inflated expectations. Secondly, it’s almost impossible to “pop” a financial bubble safely: monetary policy has large effects on the economy, which might outstrip any gains from unwinding the speculative mania. Plus, bubbles included widely outrageous expectations of gains (double digit returns, for instance) so the Fed would need to crank HARD to unwind the bubble, since people would need very high returns to abandon speculative assets.

As a matter of fact, the Fed started tightening rates by mid 1929, with the Fed discount rate reaching 6% by August, and the economy was already in a recession by October. And the stock market fell, but not that much, as Black Monday just erased the gains from the previous months: by April 1930, stock prices were at the same level as in January of the previous year. The stock market in fact worsened with the Depression becoming more pronounced, and let to a series of financial panics in 1930, 1931, 1932, and 1933. From a Ben Bernanke speech on the matter:

The popular view is that the market crash was the harbinger of the Great Depression. In fact, the weight of historical research has shown that this interpretation gets the causality largely backward. The economy was already slowing by the fall of 1929 (…), largely as a result of monetary tightness. Economic indicators, which had been uniformly strong, were becoming more mixed: The Federal Reserve's industrial production index began to decline in July, construction contracts fell sharply in August and September, and automobile sales dipped suddenly at the beginning of October.

Now, there’s a series of different arguments to be made from this. The first is that it wasn’t the crash that caused the Depression, but rather, that the unreasonably tight monetary policy the Federal Reserve pushed for caused it. That view is correct, but we’ll go back to it later. There’s also an argument to be made that the crash did cause the Depression, by erasing wealth and reducing purchasing power - but, as mentioned above, it just wasn’t big enough. Stocks aren’t a big part of wealth, and not that many people own them, plus the drop just wasn’t big enough to cause such a large response in output.

A last explanation is that the stock market crash was significant to the economy, but for different reasons. Consumers and investors were accustomed to economic vibrance; so a big dip in the Dow Jones must have rattled them. This led to deteriorated expectations of future income, mistrust in the stability of financial entities, and large uncertainties over the direction of the economy. The second effect led to more panics; the first and third to less consumption and investment. And because the Hoover administration promoted a very optimistic view of the economy, consumers were even more mistrustful.

Uncertainty bled into the economy because consumers were spending significant amounts on durable goods such as cars, washing machines, radios, etc, which were purchased on credit: their larger cost (given the rate hikes) and the uncertainty over future income led to scaling back purchases. This, in turn, negatively affected businesses, which slashed investment, laid off workers, and lowered prices, leading to unemployment growth and deflation that made the problem worse.

This is what Keynes referred to as the “paradox of thrift”: individuals and companies scaled back spending dramatically, leading to a savings glut (outside of the banking system) and to deflation that pushed up real interest rates and prevented even more credit purchases. The reason deflation occurred is that companies couldn’t reduce prices, so unsold items just piled up while demand didn’t follow. Regardless of its cause, deflation caused the inverse economic distortions than inflation does, by reducing the consumption, forcing debtors into bankruptcy, and raising unemployment.

Bank mayhem

Fifteen months later, the situation was different. The Depression had started, but there were widespread expectations of a recovery, since previous recessions in 1920, 1923, and 1926 had lasted roughly as long and the economy came roaring back. But starting in late 1930, then again in 1931 and 1932, there were a series of bank runs that collapsed the US financial system.

It’s important to know that the US banking system was really different in the early 30s. Of the roughly 25,000 banks in the United States, only a third were members of the Federal Reserve System - and the rest were not. Fed policies were also set by each regional branch, which were independent from each other and adopted different policies. Lastly, banks counted certain types of checks as reserves, and non-Fed banks kept cash in their vault, frequently by spreading it across branches.

A Nashville, Tennessee subsidiary of a corporation that invested too heavily in stocks crashed in early November. Then, similar branches of that conglomerate in Knoxville and Louisville failed too. Banks suspended operations because of the ramifications of this collapse, and creditors panicked and rushed to their local banks to withdraw. Since banks were so geographically spread, and mass media was already established, this local phenomenon was repeated across the country. In early December, bank failures were starting to end - until the fourth largest bank in the country, Bank of the United States, shut down operations. Another financial panic spread throughout the country, and the various Fed branches had contradictory responses: the Atlanta Fed loaned emergency cash to its member banks, while the St Louis Fed did not, for example. Another series of bank runs started in Chicago in 1931.

These financial panics had, unsurprisingly, negative effects. Firstly, the already damaged credit system took another large blow, slowing consumption and investment. Secondly, households started hoarding cash and banks began to accumulate reserves to respond to the high uncertainty of the time, which resulted in even worse deflation. Additionally, banks hoarding credit made the post-1933 recovery very tenuous, which meant that contractionary fiscal and particularly monetary policies in 1937 resulted in another deep recession (-10% GDP, 20% unemployment, etc). A number of farmers moved across the country to states like California, and there is no evidence that this migration hurt any locals.

The real sector

The easiest way to conceptualize the Depression is aggregate demand and aggregate supply. Uncertainty, bad policy, and other factors led to lower aggregate demand - people spending less. The government didn’t make up enough of the shortfall, so aggregate demand decreased. However, aggregate supply didn’t decrease as much, resulting in lower output, higher unemployment, and deflation. So far we’ve mostly discussed about banks, finances, and the stock market, and treated “regular people” as an afterthought. But what was the Great Depression’s way of spreading to the real economy, i.e. the economy of goods and services?

Firstly, a lot of the expansion in consumption during the 1920s was funded by credit, particularly installment buying of durables - and if you missed even one installment, durable goods were often repossessed, meaning that you’d have enormous downside risk. As a result, rate hikes and uncertainty, plus risk of joblessness, meant that families both stopped spending on durable goods (bad for the economy) and replaced their other spending with paying off previous debts, resulting in lower aggregate spending and a generalized slump. An issue here is what Keynes called “the paradox of thrift”: people were worried about the future, so they spent less, resulting in lower employment, lower incomes, and more uncertainty, so savings continued piling on.

Another issue that made this worse is that unemployment was fairly high throughout the industrialized world during most of the 1920s, although not in the US specifically. The American labor market, however, had a very high degree of concentration (which lowers wages) and internal labor markets abounded, resulting in very inflexible contracts and “sticky wages”, i.e. contracts that can’t be adjusted down. This problem was worsened because companies thought that very inflexible wages were good for business and worker morale. Anyhow, deflation and sticky wages resulted in higher real wages, which meant that labor became too expensive during an economic slump - increasing unemployment more than otherwise.

Plus, the bank panics both made uncertainty worse, worsened expectations of future income, raised credit costs, and thereforer reduced lending - resulting in credit rationing that hurt companies and consumers at a time when the Depression might have become less severe. This was especially bad for farmers and rural banks, which were a major part of the financial system and helped worsen the panics.

Speaking of farms, the farming sector was especially important for the Great Depression, since farmers made up 25% of the population in 1929 (compared to 1.6% presently). Deflation shows up here for the umpteenth time, but it was particularly worse for farm products: cotton, for example, dropped 29% between the final quarter of 1929 and the third quarter of 1930. Because most farmers were small operations at the time, incomes dropped 25% (compared to 6% for non-farmers) and drove many to default on their (numerous) loans and for banks to collapse - contributing to the ongoing financial panics.

Great Depression: World Tour

The recession was already bad by 1931. Then, it got worse. On September 21, 1931 Great Britain withdrew from the gold standard. Fearing the United States would do the same, foreigners demanded more and more American gold, and Americans intensified the aforementioned accumulation of money. This sharply curtailed the supply of money and deepened the already occurring deflationary recession.

To stem the loss of gold reserves, the New York Fed decided to raise rates to attract foreign investment and reduce losses. This worsened economic prospects, and the dynamics of the 1930-31 panic heightened, leading to more bank failures and to a sluggish federal response - since the lower rates harmed banks, which were not getting nearly enough Fed assistance. By late 1932, Herbert Hoover was already out of office, but Franklin Roosevelt would not be sworn in until March, meaning that the only action undertaken was the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which would lend to banks and other corporations. But since those loans would be public, banks remained reticent to borrow, since it would admit their weakness to customers who still trusted them and potentially lead to further panics.

The international aspect of the Depression cannot be ignored. Deflation became endemic throughout the world in the early 1930s, due to persistent bank failures and reductions of consumption and investment. Additionally, countries had incredibly strange monetary policies at the time, such as France hoarding gold through most of the 1920s that led to monetary shortages throughout the world and to incipient deflationary pressures. The maldistribution of global gold reserves due to American and French hoarding, both sterilized by destroying money, worsened global pressures and the American recession was the coup de grace for the global economy.

Another issue was the beginning of a global trade war after the US passed the Hawley-Smoot Tariff Act in 1930, which raised import duties on a broad array of products. This act pretty clearly hurt exporting sectors, although it may have benefitted some manufacturers. However, it’s also clear that it attracted retaliation from a large number of nations, which might have counteracted the benefits of the act, and also led to a current account surplus that probably worsened the maldistribution issue, particularly outside the United States. Regardless, the effects of the Act weren’t especially large and are hard to disentangle from the generalized economic collapse and the worldwide deflation.

A factor to consider for the international aspect was the lack of a global economic hegemon that controlled the reserve currency. Before World War One, that role was played by Britain; after World War Two, by the United States. But in the interwar period, there was no single economic hegemon, which made cooperation between countries (for instance, to prevent some of them from hoarding gold) much harder. There is some controversy about this view, however, but I’d argue that things like hoarding gold and the collapse of international trade might have been avoided if there was a big country in charge.

All that glitters…

Here comes the big one: the Gold standard. We’ve been hinting at this here and there, but let’s tackle this head on: was the gold standard bad? And did it cause the Great Depression?

Yes and yes. Let’s get deep into the issue. The gold standard was a system by which the currencies of all countries were backed by gold. Because devaluing currencies was not possible under this system, countries that had negative balances of payments had to undergo deflation, and countries with positive balances would have to inflate their money supply. The former endured what they had to, but the latter did as they liked - resulting in the previously mentioned gold stockpiles of France and, to a much lesser degree, the United States. To prevent outflows of gold that caused heightened deflation, nations sharply raised interest rates, contributing to deflation (paradoxically) and worsening economic woes. Additionally, the gold standard came wedded to the extremely restrictive measures on Central Bank powers mentioned above, that made the recession much more severe and let bank runs continue unimpeded.

In fact, the gold standard meant that, when countries started devaluing their currency (such as the UK in 1931) other countries faced losses of gold reserves, which were counteracted by reducing the money supply. In a recession. With out-of-control deflation. In fact, one of the many reasons protectionism became so common during this period was that countries were simply trying to maintain their gold supply at all costs, to not endure worsening economic conditions.

And the Depression itself only started because the Federal Reserve, besides from trying to pop an asset bubble, was also getting concerned about the drainage of US gold reserves into France. Since the gold standard required countries to offset gold inflows, and France specifically refused to ever do it, then nobody had any other choice than to raise interest rates. And the gold standard made the bank failures particularly much worse, since besides the endogenous shrinkage of the money supply, there was also the issue of lower credit and reduced investment, which meant an even lower supply of money.

But the gold standard wasn’t considred a policy back then; it was considered the cornerstone of economic prosperity. Herbert Hoover said “We have gold because we cannot trust governments”, which was a clear indication of why the gold standard was considered, well, the gold standard of monetary policy: trust, reliability, and no inflationary potential. Politicians were wedded to the gold standard regime for seemingly inexplicable reasons, resulting in a reluctance to actually solve any problems that prolonged and worsened the Depression. The Federal Reserve actually had enough gold to inflate the money supply and still back the gold standard, but refused to do it: partly because of the fear of reigniting stock market speculation, but also partly because of the Board of Governor’s unwillingness to do anything (due to deadlock and a power vacuum).

The end

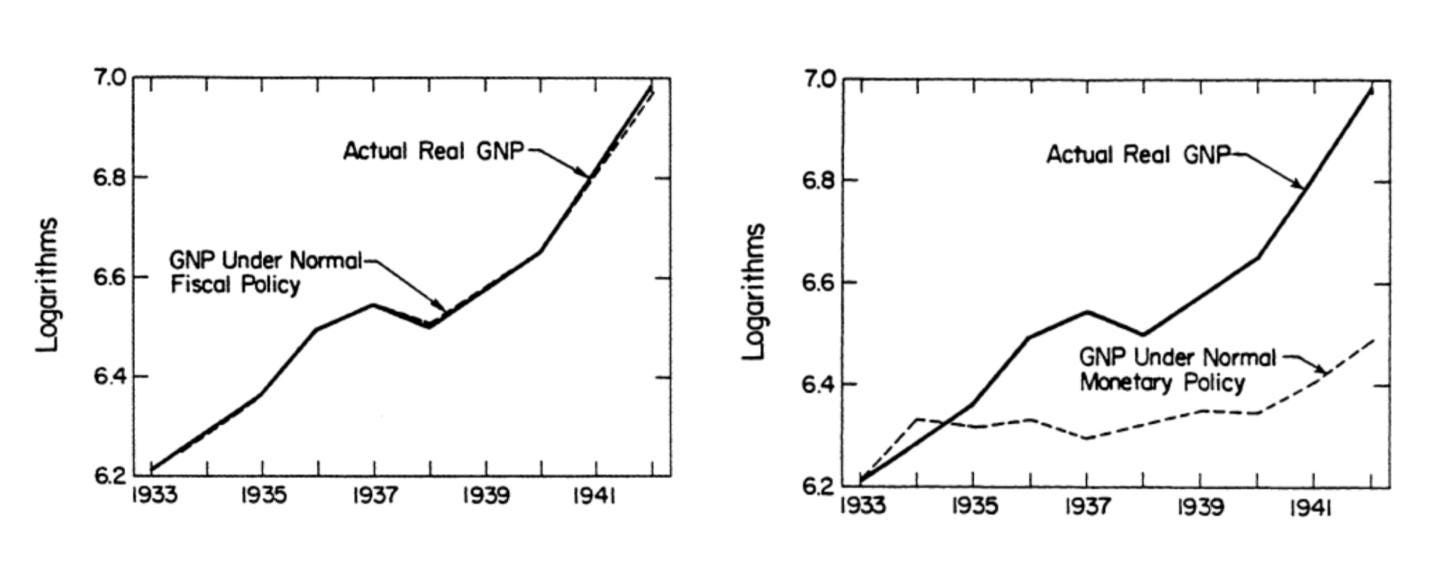

The common narrative is that the New Deal ended the Great Depression, but it’s not quite right. The stimulus, according to Paul Krugman, was about 3% of GDP - a big number, although it can be noted that the gap between actual and potential GDP at the peak of the depression was 42%. So the New Deal stimulus was 14 times too small, although it did do its job quite effectively. So what did end it?

So far, the causes of the Great Depression seem primarily monetary: interest rates that were too high, bad responses to the financial market crashing, the gold standard choking the entire economy, etc. Logically, the solution should have also been monetary. The Depression ended in 1933; not so coincidentally, Franklin Roosevelt announced he would take the US off the gold standard in the same year.

The reason the announcement triggered a recovery was that FDR signaled a new monetary regime, i.e. a new way of doing monetary policy. Whereas Hoover promised stable prices under the gold standard, Roosevelt would do whatever it took to grow the economy and inflate the economy. As a result, moderate amounts of monetary and fiscal stimulus went a long way, since it acted as confirmation of a new set of expectations: that the US economy would grow, whatever it took.

Between 1933 and 1945, the supply of money grew roughly 15% a year, an incredible amount. The reason why this happened is debated, but probably includes international trade and the deteriorating political situation in Europe, particularly by the late 30s. The US going off the gold standard was relevant because the inflow of gold was not sterilized (i.e. destroy or create paper money to match the supply of gold) - under the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, the Treasury only had to sterilize gold outflows not inflows. Real interest rates declined sharply, and investment and consumption reacted along the expected lines. GDP grew, on average, 9% during FDR’s term, and unemployment dropped by 11pp (from 25% to 14%) in just six years.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing: the economy fell back into a big recession again in 1937, which lasted a year: GDP dropped 11% (the third worst recession in US history, after the Great Depression proper and the recession of 1920 to 1921), and unemployment climbed back up to 19%. The reasons here were twofold: the first was a drastic reduction of the deficit (2.5% of GDP), and a highly contractionary monetary policy, which raised bank reserve requirements, sterilized gold inflows, and once again tried to pop a (this time fully imaginary) stock market bubble. Fortunately everyone realized the error of their ways and rolled those bad policies back.

Conclusion

“To study macroeconomics, study the biggest calamity to hit the U.S. and world economies” - this is how Ben Bernanke described his interest in the Great Depression, about which he spent a significant chunk of his academic career. The Depression fascinated economists for the following 40 years, and fears of repeating it were crucial in causing the Great Inflation of the 1970s.

But we can draw two (maybe three) lessons from the Depression. The first is that monetary policy is extremely important, and there are goals it can accomplish (stimulate the economy) and ones it can’t (curb speculation painlessly). The second is that interest rates aren’t a measure of the stance of monetary policy - 5% interest rates are deflationary with 1% inflation, and inflationary with 9% inflation. So low rates don’t mean that monetary policy is expansionary - often they mean just the opposite, that it was too tight in the past.

The final lesson is about recoveries. Oftentimes, just the commitment to help the economy recover can go a long way. The Bank of Japan had very low interest rates and the country still went through a mini Depression: high unemployment, paltry growth, deflation. When it promised it would churn out cash until the economy got better, it got better - because people trusted it. And on the other side, Paul Volcker showing the Fed was dead serious about stopping inflation no matter the costs (“spilling blood, lots of blood, other people’s blood”) was how he actually tamed it.

There’s another thing to look at: stimulus. Just as stimulating the economy might do nothing without proper monetary support, so can taking it away be disastrous if the economy either isn’t ready or if it sends the wrong signals. Worrying about imaginary things that haven’t happened yet (a second stock market crash, a big inflation) isn’t a productive attitude when livelihoods hang in the balance.

Sources

Gary Richardson, “The Great Depression”, Federal Reserve History, 2013

David Wheelock, “The Great Depression: An Overview”

Ben Bernanke, “On Milton Friedman's Ninetieth Birthday”, Speech, 2002

Greg Ip, “Long Study of Great Depression Has Shaped Bernanke's Views”, the Wall Street Journal, 2005

Stock market crash

Richardson, Komai, Gou, & Park, “Stock Market Crash of 1929”, Federal Reserve History, 2013

Romer (1988), “The Great Crash and the Onset of the Great Depression”

Ben Bernanke, “Asset-Price "Bubbles" and Monetary Policy”, Speech, 2002

Eichengreen (2004), “Viewpoint: Understanding the Great Depression”

Eichengreen (1992), “The Origins and Nature of the Great Slump Revisited”

Brad DeLong, “1929: The Great Crash and the Great Depression”

Bank panics

Gary Richardson, “Banking Panics of 1930-31”, Federal Reserve History, 2013

Kristie Engemann, “Banking Panics of 1931-33”, Federal Reserve History, 2013

Temin (1993), “Transmission of the Great Depression”

Das, Kitchener, & Vossmayer, “Bank networks and systemic risk in the Great Depression”, VoxEU, 2019

Real sector

Romer (1993), “The Nation in Depression”

Bernanke (1994), “The Macroeconomics of the Great Depression: A Comparative Approach”

Degorce & Monnet, “The Great Depression, banking crises, and Keynes' paradox of thrift”, VoxEU, 2020

The global panic

Irwin (2010), “Did France Cause the Great Depression?”

Eichengreen (1987), “Hegemonic Stability Theories of the International Monetary System”

The gold standard

Eichengreen & Temin (1997), “The Gold Standard and the Great Depression”

Eichengreen & Temin, “Fetters of gold and paper”, VoxEU, 2010

The end

Paul Krugman, “New Deal economics”, The New York Times, 2008

Temin & Wigmore (1990), “The end of one big deflation”

Romer (1992), “What Ended the Great Depression?”

Eggertson (2008), “Great Expectations and the End of the Depression”

Patricia Waiwood, “Recession of 1937–38”, Federal Reserve History, 2013

Christina Romer, “The Lessons of 1937”, The Economist, 2009

Douglas Irwin, “What caused the recession of 1937-38?”, 2011, VoxEU

Gerald Dwyer, “Excess Reserves in the 1930s: A Precautionary Tale”, Atlanta Fed, 2010