A well-known story tells of a finance professor and a student who come across a $100 bill lying on the ground. As the student stops to pick it up, the professor says, “Don’t bother—if it were really a $100 bill, it wouldn’t be there.”

Malkiel (2003), “The Efficient Market Hypothesis and its Critics”

Many people like talking about the stock market. Movies such as Wall Street, the Big Short, and the Wolf of Wall Street depict the financial sector, to critical and commercial acclaim. Are these people actually any good at their job, or what?

Can stock market forecasters forecast the stock market?

It seemed a plausible assumption that if we could demonstrate the existence in individuals or organizations of the ability to foretell the elusive fluctuations, either of particular stocks, or of stocks in general, this might lead to the identification of economic theories or statistical practices whose soundness had been established by successful prediction.

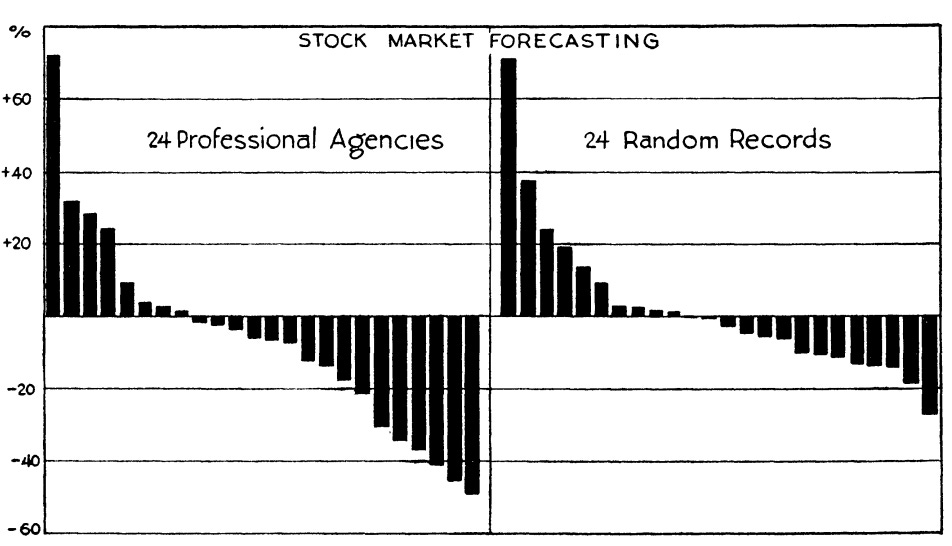

(…) A review of the various statistical tests, applied to the records for this period, of [these forecasters], indicates that the most successful records are little, if any, better than what might be expected to result from pure chance. There is some evidence, on the other hand, to indicate that the least successful records are worse than what could reasonably be attributed to chance.

Is it possible to predict future stock prices? This is a fundamental question for finance: if it were, then there would be infinite profits to be made in day trading.

In 1932, economist/econometrician/businessman Alfred Cowles asked precisely this question: can stock market forecasters forecast? The answer, as seen above, was “no”. They did not get, on average, better results than random chance and maybe even got substantially worse ones. This is true regardless of whether you look at financial advisors looking at individual stocks (they did 1.4% worse than the average result), insurance companies (1.2% worse), newspaper predictions (50% batting average from the Wall Street Journal), and various financial publications (4% below random chance). This is profoundly underwhelming - why did this happen?

… if the flow of information is unimpeded and information is immediately reflected in stock prices, then tomorrow’s price change will reflect only tomorrow’s news and will be independent of the price changes today. But news is by definition unpredictable and, thus, resulting price changes must be unpredictable and random. As a result, prices fully reflect all known information, and even uninformed investors buying a diversified portfolio at the tableau of prices given by the market will obtain a rate of return as generous as that achieved by the experts. (…) a blindfolded chimpanzee throwing darts at the Wall Street Journal could select a portfolio that would do as well as the experts.

Malkiel (2003), “The Efficient Market Hypothesis and its Critics”

The primary explanation economists use for why stock forecasters fail at their jobs so much is called the “Efficient Markets Hypothesis”. The basis of the EMH is the theory of rational expectations, which I’ve already covered in some detail, so a quick recap. Under rational expectations, markets function as if individuals operate with a full working model of the market in their heads that has complete information about all the relevant factors. Because of this, then there is no information left on the table, and forecasts of the future do come true - except when something unexpected happens. The “as if” part is crucial - nobody who believes expectations are rational believes it is an accurate representation of individual behavior (if they did, they should be placed in a mental institution); rather, the “as if” nature of the assumption means that the system as a whole functions in a way that would happen if individuals were rational, because irrational behavior would get punished and individuals who engage in it would not be able to participate in the market (I’ve also written a bit on as if assumptions too). Prices reflect available information (all of it, at the limit), which means people aren’t systematically wrong in their expectations - you can’t fool all of the people all of the time. It also means economists can’t actually make money off of market inefficiencies - because if we can, other people can too.

Asset prices are similar. The price of a financial asset (say, a share of a company, or a bond, or some fancy other thing) reflects, in general, the expected future flow of profits it will generate. If the financial market works as if individuals are rational, then all the relevant publicly available information would already be incorporated into prices. Since there is no way to tell what new information will be revealed, then future prices are fundamentally unpredictable - only new information will move them, and if it was predictable it’d have already been “priced in”. Stock market forecasters cannot forecast the stock market by definition.

What does “efficient” mean?

Assume a financial market without many barriers to entry, with a healthy amount of competition, and where acquiring information isn’t excessively costly. The Efficient Markets Hypothesis, or EMH, has three forms:

Weak form: all previous data on prices has already been reflected, making predicting prices impossible - unless you have “new” or “private” information.

Semi-strong form: on top of all previous information already being priced in, all new information is also priced in immediately - such as breaking news or corporate announcements.

Strong form: not only is all past and present public information priced into the market, all private information is too - nobody beats the market.1

Now, the strong form is obviously bonkers: if you have information other people don’t, then it’s obviously possible for you to profit off of it. Instead of using an example from Billions, I’ll use one from real life: in 1954, economist Armen Alchian figured out a specific component used in nuclear bomb by looking at the (public) stock prices for chemical companies - right after the a nuclear test was successful, the stock for lithium producers rose, but not for other candidates. His paper was ruled out to be a national security risk, and was confiscated and destroyed. So people with advance knowledge about what the product was could have profited off the Operation Castle drop - not supporting the strong form of the EMH. The semi-strong EMH, however, is partially supported by a variety of event studies: new developments that could affect the stock market are reflected in stock prices almost immediately. The “event study” literature (i.e. studies that focus on how an individual occurrence affects some variable - say, a nuclear test on lithium stock prices) seems to not disprove that big changes in information result in big changes in asset prices.

Either way, whether or not the EMH is true depends on whose criteria you’re meeting. If you think it’s supposed to be a description of events or behavior, then it’s obviously not an accurate one - anyone who thinks that the people from Wolf of Wall Street are doing their due dilligence is clearly delusional. But, as long as they respond to incentives, finance types will end up getting “punished” by the market if their behavior is not as if it was optimal. The opposite criterion isn’t whether it describes event correctly, but rather, whether it makes correct predictions - i.e. conditional statements about some potential course of events. If The EMH said “all information is adopted into prices”, and some big event came and prices didn’t budge, it’d be considered false. Worth pointing out that incorrect descriptions of behavior are not the same as incorrect predictions - the criterion Fama uses to judge himself is whether or not his theory predicts false things, not describes reality correctly2.

The core of the Efficient Markets Hypothesis is that asset prices reflect all publicly available information. Because only new information is going to affect them, and new information is an unknown unknown, then future asset prices are unpredictable. This has three major (empirically verifiable) implications:

No rules can be used to simply decide what stocks to pick. Rules like “buy when the market went up” rely on there being information that’s not already incorporated - which, if the EMH held, would be false.

Is it true? In general, yes; however, there is a small amount of autocorrelation (i.e. small predictive power from previous values) between prices, which means some rules work in the shortest of terms for very small gains.Financial analysts can’t consistently overperform the market. If prices are unpredictable, all successes are “luck” and non-systematic - callling the last crash is no indication of calling the next one.

Is it true? It’s very complicated to test, so rain check.New information is incorporated into prices as soon as available. As long as the costs of acquiring information or trading in the market are not too high, new information is nearly immediately reflected in prices.

Is it true? Basically yes.

Some criticisms

I have personally tried to invest money, my client’s money and my own, in every single anomaly and predictive device that academics have dreamed up. … I have attempted to exploit the so-called year-end anomalies and a whole variety of strategies supposedly documented by academic research. And I have yet to make a nickel on any of these supposed market inefficiencies … a true market inefficiency ought to be an exploitable opportunity. If there’s nothing investors can exploit in a systematic way, time in and time out, then it’s very hard to say that information is not being properly incorporated into stock prices.

Richard Roll, finance economist and portfolio manager, at a symposium (page 23)

The major criticism concerns behavioral finance and the claims it makes, so I’ll leave it for last. Pretty entertainingly, the main figure in that group, Robert Shiller, won the Nobel Prize alongside Fama in 2011 (at least it was better than when they gave it to some guy who hated Ed Prescott and proved his life’s work wrong a few years after they gave it to… Ed Prescott).

The first criticism, a really bad one, is that financial crises still occur, therefore markets can’t be efficient. Implicit in this statement is that financial crises are somehow predictable, which is not really the case under the EMH - so markets can be efficient and crash; efficiency here refers to information, not to “goodness”. The related fact that some people call market crashes or bubbles isn’t really incompatible either - you can occasionally outperform the market, but nobody does it systematically. Many people can say that the stock market could crash, or that price growth in asset X or Y is actually a speculative bubble, but they can’t really say when it will happen (which is the actual meat of the prediction), and can’t do it again and again. “They just got lucky” isn’t really a satisfactory answer, so this one might stick out for some.

A second counterpoint against the EMH is that, if all information is already in prices, then why would anyone trade anything, since there’s no profits to be made. This argument makes a big mistake, that private information and public information are the same. If the strong form EMH was true, then yeah, the stock market would be useless. But it’s not, because insider trading dumps move stock prices and therefore mean that they contain previously unknown information. Then, stock picking is a sometimes profitable endeavor, because some information that is private can be acquired and profited off of (I’d rather call it “costly” and “costless” information but whatever I’m not a Nobel Laureate).

But wait, you might be thinking: using any model of what asset prices should be results in too much variation in actual prices for them to be efficient. This seems like a clear-cut anomaly that is not accounted for by the EMH: prices changed without any relevant information. Issue is that if you use a model of asset pricing to model asset prices, you are assuming it is correct and that you correctly estimated it - but neither is necessarily true. If you say “markets aren’t efficient because my model says so”, then it could be that markets are inefficient, that they’re efficient and your model is wrong, or both - but you can’t really tell them apart ex ante.

The third is what’s known as momentum - a small but significant positive correlation between successive prices. This would result in the weak form EMH being partially violated, since there is some predictability in asset prices. These results are small but statistically significant, which doesn’t necessarily mean they are economically significant - it’s not really possible to systematically profit off of “stock momentum” because of the costs involved in transactions themselves.

In contrast, over the long term, there is evidence of significant long term negative autocorrelation - that is, mean reversal, which is, in other words, that stocks go down after going up, and that they go up after going down, meaning that there is some degree of predictability. The problem is that there’s some periods with mean reversal and others without it - and the Great Depression has the most of it, which might not make it very representative of normal times. And even then, the mean reversal might reflect changes in monetary policy (i.e. interest rates) over the business cycles - stocks might go down after going up because interest rates are higher, as prices of bonds and stocks move in tandem to avoid arbitrage. It’s also possible that people’s willingness to take risks is also mean-reverting over the business cycle, which could be reasonable and could account for some of that.

A related issue is the equity risk premium: over the long term, stocks have had almost twice the average return as bonds and other safe assets, which means that either they’re way more risky (unlikely) or that something is up. First, it might be a sample issue: the Great Depression, as above, was not a good time for stocks because of uncertainty over their returns - so assets being overpriced or underpriced in hindsight is different to them actually being over/underpriced; if the available information pointed to the economy being in a rut for a long time, then they would have grown very slowly, and then very quickly once accurate information was available.

The last case to argue about are bubbles: are asset bubbles, i.e. assets going up in value at astronomic rates, and then plummeting, proof that the EMH is false? Robert Shiller, the bad guy for EMH faithful and good guy for EMH believers, thinks it does - because people don’t act rationally (per psychology), bubbles are wholly irrational phenomena and tear a big hole in the EMH - prices going up without any information whatsoever. But the issue is that many bubbles are centered around business opportunities where the upside is not especially clear: cryptocurrency, the late 90s dot com companies, many of the imperialism-related ventures, etc. If it’s not especially clear what the upside should be, it’s possible incorrect information gets incorporated into prices without anyone knowing better; information being wrong in hindsight doesn’t mean that information is clearly wrong at the time. Another issue is that, if stock prices are unpredictable, then there’s a pretty big risk in selling an asset you believe is overpriced: that it’ll continue gaining value and you’ll lose out on profits (and also, probably, a job). The point isn’t really that bubbles never happen; is that it’s impossible to systematically, reliably profit from them.3

Conclusion

I think that the main takeaway here is that, even if information is perfectly and completely incorporated into financial markets (which is more an ideal type and less an intended description of reality, let alone human behavior), the information itself is actually very hard to interpret directly - “is the economy going to enter a recession” is the kind of question you can get a Nobel Prize, or make a fortune, by answering. The Efficient Markets Hypothesis is a shockingly humble theory, despite the boastful name: you’re not smarter than everyone else, you’re not going to beat the market, you should just play it safe and go with the flow.

Sources

Previous posts on rationality and rational expectations

Cowles (1929), “Can Stock Market Forecasters Forecast?”

John Cochrane, “Eugene F. Fama, Efficient Markets, and the Nobel Prize”, 2014, Chicago Booth Review (longer version available here, on his blog)

Fama (1970), “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work”

Fama (1991), “Efficient Capital Markets: II”

Malkiel (2003), “The Efficient Market Hypothesis and Its Critics”

Fama (1997), “Market Efficiency, Long-Term Returns, and Behavioral Finance”

Fama & French (2006), “Dissecting Anomalies”

John Cochrane, “Bob Shiller's Nobel”, 2014

Shiller (2001), “Bubbles, Human Judgment, and Expert Opinion”

Actually a big implication of the strong EMH is that insider trading shouldn’t be a crime because they don’t actually know more than the information reflected by the market.

The “models as maps” allegory cuts both ways: they can be understood as representations of reality (descriptive) or as guides to get from A to B (predictive). And nobody wants a map to marvel at the scale of human ingenuity, they want a map to get somewhere.

Also the “housing bubble” is not a very good explanation of things: the economy was strong and the supply of housing was severely constrained, so expectations of higher and higher prices weren’t unreasonable. Prices grew the most in supply-constrained cities, and construction in places with lax zoning. Most borrowers were middle class, and mortgage defaults don’t happen randomly en masse; human beings are not flocks of Japanese birds. The Fed tried to tank the economy because oil was expensive, and they tanked it so bad that a bunch of people who got crappy loans defaulted, which brought a ton of banks close to bankruptcy, which meant they had to be bailed out and that the economy faced a really severe recession because financial crises are, surprise surprise, really bad.

> A second counterpoint against the EMH is that, if all information is already in prices, then why would anyone trade anything, since there’s no profits to be made.

It can also make sense to trade because:

- different people have different risk appetites/time preferences. (so young people trade with near-retirees.)

- you can get paid market-making fees for it.

The first often happens by accident; most retail traders don't know what "risk-adjusted return" or "Sharpe ratios" are, and when they buy something because the return looks good they're actually buying higher risk. If you think a specific tech stock is going to go up, you can put 100% of your portfolio into it - but you can also borrow more money from other people (assuming interest rates work out), put 200% of your portfolio into QQQ, and end up with a safer portfolio and the same return.

Brilliant article, thank you!