A while ago, I posted about the Phillips Curve. Back then, I didn’t think it was real, but I changed my mindt. Now I do, but I still don’t think it’s very important or useful to help guide policy, only to help diagnose it.

Always and everywhere a sweetener phenomenon

On October 14th, 2012, Donald Trump (back then not a political figure) tweeted: “I have never seen a thin person drinking Diet Coke”. Common sense would seem to imply there is a negative correlation between weight and the sugar content of a carbonated beverage. Regardless of the underlying causes, we should be seeing a negative correlation between weight and sugar content in the data - graphically, the “Trump Curve” would have a negative slope.

You could specify two different kinds of stories here: one where drinking diet sodas causes higher weight, and one where the causes of higher weight and the causes of drinking diet soda are the same. The first one is pretty straightforward, while the latter requires more development. A simple model for weight is “calories in, calories out”, aka how many calories the body needs vs how many are consumed - diet sodas still have a high caloric content, so drinking them overcalorizes the body and therefore leads to weight gain. But you could justify the relationship the other way around, by saying that reducing the sugar content in sodas results in consuming a higher amount of them, causing weight gain. And the last kind of story might result from the person trying to increase or decrease their weight by adjusting their diet, which would also imply a different level of soda consumption.

But Trump (2012) is claiming something different - that the slope of the Trump Curve is flat. How could this be? Very simple. Imagine that the person tries to regulate their health, which includes their weight, by changing their diet. This means different levels of calory, sugar, and fat consumption, and therefore different amounts of sugar in the sodas. Since too little and too much weight are both problems, “fattening” people will drink non-diet soda and “thinning” people will drink diet soda. But because Trump’s claims only compare the levels, there appears to be no relation between sugar content and weight. If there were, this would mean the person’s diet is inadequate relative to their weight target.

This has nothing to do with inflation, unemployment, or the role of monetary policy.

The role of dietary policy

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

Milton Friedman, (1970) “Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory”

I’ve already stated my views on inflation, unemployment, and how monetary policy ties them together, but I’ll state it again just to be safe: inflation is always and everywhere a phenomenon of too much money chasing too little stuff.

Let’s start with the quantity theory of money (technically the equation of exchange), which is based on a statement that is by definition true: MV = Py. M is the supply of money, V its velocity, P the price level, y real output. “MV” stands for the total amount of money changing hands in the economy in a time period; “Py”, for the total amount of stuff being produced in the economy, without adjusting for inflation. This statement is true, always and everywhere, because both sides equal Y, aka nominal income/output, aka nominal GDP.

Consequently, using it without specifying behavior cannot really yield much insight: an increase in M could cause an increase in P - or in y, or a decrease in V. Normally, it’s assumed V is fixed in the short term, and when the economy is in what the neoclassicals called equilibrium and the Keynesians called full employment1, y is also fixed (so that monetary policy cannot stimulate the real economy), and therefore changes in M equal changes in P. Over the long term, because the amount of transactions has to equal the amount of stuff that’s changing hands, inflation equals changes in M minus changes in real output - and this is generally true. During the short term, y is normally believed to be inflexible upwards but not downwards - aka capable of decreasing but not increasing. This means that, in recessions, increasing the supply of money can actually stimulate real output back to its pre-recession levels.

The relationship with inflation is pretty clear: if the total amount of spending in the economy exceeds the maximum possible amount of stuff the economy has at its disposal (either nationally produced or imported) during that time period, then prices will increase. If the total amount of spending is too low, then inflation will be too low also. Obviously, to control inflation, one must keep the total amount of spending in the economy balanced. Evidently, a decrease in the real amount of stuff results in a higher rate of inflation, because nominal spending at the previously balanced level is now too high for the actual capacity of the economy. Although there are actually three possibilities: inflation does increase, because consumers spend more on the affected orices and the same on everything else (say, by saving less), or inflation doesn’t increase, because either consumers spend more on the affected product(s) and less on others, or the other way around.

This has a clear corollary in the labor market: “balanced” spending should result in a balanced labor market, whereas too little spending results on too little output and therefore employment that is too low. But the relationship between too high spending and too high employment is controversial: it’s frequently observed that sudden spikes in inflation are accompanied by a very tight labor market. The two possible interpretations are that the excessive amount of spending tightened the labor market, resulting in excessive wage growth, resulting in excessive prices. This implies that real wages have to increase, at least initially, during the inflationary period. The other possible interpretation is that excessive spending raises prices, which forces wages to increase, but because prices increase more, inflation-adjusted wages get lower and therefore hiring is cheaper. Obviously, in this scenario, real wages fall. Both are possible, perhaps simultaneously in different parts of the economy, but it’s clear that average real wages must fall for this to be true.

Unnatural rates

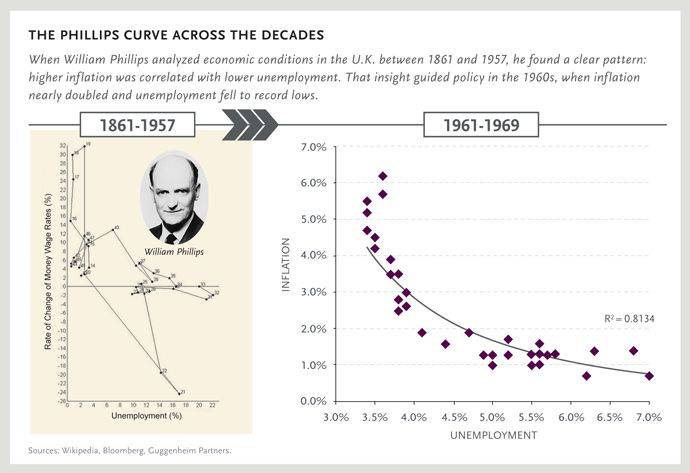

The Phillips Curve is the relationship between inflation and unemployment, which has been empirically observed to be mostly negative. It was first proposed by a man called Arthur Phillips in 1948, as a relationship between unemployment and wages, and later extended from wages to prices by Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow in 1960. Now, both outline the same thought process as above: money vs stuff. The difference here is that different mechanisms to keep this relationship going imply different effects of policy and therefore different consequences.

A big concept here is the NAIRU - the non accelerating inflation rate of unemployment2. If you believe in the unemployment - wages - inflation version, then each rate of unemployment has a correlate in the inflation rate. This means that, for any given inflation goal, there is an implicit level of unemployment that matches it. Because the labor market is a market, there is also a rate of unemployment that clears it - the natural rate. Now, the NAIRU and the natural rate aren’t just conceptually different, they also might be different levels. If the NAIRU is smaller than the natural rate, then the inflation target would result in “too much” unemployment relative to the market; if it’s larger, in “too little”. And targeting the natural rate in the first scenario would result in “too much” inflation, versus “too little” in the latter.

I’m not really interested in going over the differences between, say, Samuelson and Friedman and the Old Monetarists and the Old Keynesians, because it’s not the point of this post and because reading a lot of 70 year old papers that are almost entirely wrong both ways is not very productive. I’m just going to talk about the conclusions that the mainstream “Old Keynesian” views reached, which also generally changed over time (to make this even more of a pain).

TL; DR, the Old Keynesians ended up settling on “the natural rate is low, the NAIRU is low, and inflation doesn’t respond a lot to differences between potential and actual spending” - the slope of the Phillips Curve was implied to be really steep. This resulted in the Federal Reserve believing inflation wasn’t a big problem, that reducing it would be too painful, and that there were better non-monetary policies that could reduce it. In turn, this boiled over into their estimates of the output gap and the natural rate - which explains why monetary policy was not discretionary in the 1970s, but rather was extremely rules-based. A particularly flawed part of Old Keynesianism was its cavalier treatment of labor market imperfections, which made the Phillips Curve be mostly based on macroeconometric regressions and not really on microeconomic theory. They also used faulty econometrics to make all empirical estimates, but that’s neither here nor there because everyone else did.

After the Great Inflation caused Old Keynesianism’s demise, economists split into two camps, with opposing views on how to procede. The New Classicals thought keynesian doctrine was almost wholly wrong and should be scrapped, and instead eliminated the Phillips Curve from macroeconomics and built models around real shocks and rational utility-maximizing agents. The New Keynesians, however, thought that a better understanding of microeconomic imperfections, particularly in the labor market, could restore some of the traditional Keynesian ideas, and ended up with a Phillips Curve that largely depended on price imperfections, economic slack, and inflation expectations.3

Then empirical observations threw a thorn into everyone’s sides: the Phillips Curve basically disappeared from view after the 1970s. Once the Volcker disinflation was over, there was basically no relationship between inflation and either unemployment or economic slack - the Phillips Curve was a flat line. Inflation could basically be modelled as a random walk around 2%, and many people wondered if it was even related to monetary policy at all. The Fed was stimulative for a big part of the 2010s, and yet it was incapable of raising inflation.

Fat, thin, regular, diet

But let’s take a step back and look at the basics. Total spending above potential implies higher inflation and lower unemployment; below potential implies lower inflation and higher unemployment. Supply shocks raise or lower both at once. This means that the true Phillips Curve has a negative, but slightly flat, slope. The role of expectations is a mess, but basically they keep the inflation rate anchored around the target because people expect the Fed to keep it at that level.

The issue is that this assumes monetary policy is not systematic, i.e. that the Fed doesn’t routinely decrease total spending during inflationary periods and decrease them during recessions. If the Fed didn’t do that, then overcooling and overheating would shift both inflation and unemployment up and down, and there would be a Phillips Curve with a sharp negative slope. This would be very bad, because recessions and inflation aren’t ideal. Consequently, policymakers ameliorate recessions and moderate expansions, which keeps the data very stable. If you systematically correct inflation and unemployment so they’re neither insufficient nor excessive, then inflation and unemployment will always remain bounded within certain values. Similarly, if you charted inflation and interest rates, there would be no correlation, because interest rates are utilized to control inflation.

The existence of an ex ante Phillips Curve, i.e. a theoretical relationship between inflation and unemployment, is not necessarily the same as the existence of an ex post Phillips Curve - one that exists. Thus, the Phillips Curve’s vanishing act is not a sign that macroeconomics has gone “bad”, or that monetary policy is acting on flawed premises, but rather, than there being no evidence for an ex-post relationship between slack and inflation means that both slack and inflation were being kept at bay. Likewise, a resurgence of the Phillips Curve relationship would signal that monetary policy is bad, not good - and therefore that exploiting the Phillips Curve always results in suboptimal policy, since the relationship continues to exist.

If monetary policy was always optimal, then the economy would always be at potential, and any changes in inflation or unemployment (absent big supply shocks) would be caused by idiosyncratic changes to real factors that shift either slightly up or slightly down. And with supply shocks, then all changes to both inflation and unemployment would raise both, so a Fed that doesn’t respond to them as to not do anything unnecessary would lead to a systematically positively sloped Phillips Curve.

This also obviously entails that, for example, the relationship between money and prices (aka the Quantity Theory of Money) will not show up in the data if the policy variables are implemented systematically. For example, you can see the Quantity Theory hold in Argentina but not the United States because the Federal Reserve systematically offsets inflationary shocks while the Central Bank of Argentina does not, so big balance sheet expansions don’t move the needle on the US’s CPI but Argentina’s money-prices relationship has been one-to-one since the early 2000s.

Mostly Harmless Econometrics

The Japanese data have been particularly valuable because the Bank of Japan was very obliging for some 15 years from 1948 to 1963 and produced very wide movements in the rate of change in the quantity of money. (…) Unfortunately for science, in 1963 they discovered monetarism and they started to increase the quantity of money at a fairly stable rate and now we are not able to get much more information from the Japanese experience.

Milton Friedman, (1970) “Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory”

There’s also several big issues with the “data generating process” here. Firstly, the fact that policy aims to systematically stabilize the variables in question means that there is very limited variability in both of the observed variables of any estimated regression, which results in increasingly unreliable estimators the lower variability is. The more variance your data has, the more of the causal relationship you capture - and capturing very little of it is inevitable if your whole goal is to keep the variance low. This would mean that, absent all else, you would estimate a much weaker relationship between money and prices or inflation and slack than in reality, simply because the sample is systematically limited to a very narrow interval.

The second issue, which I’ve touched upon previously, is simultaneity. Simultaneity occurs when the dependent and independent variables being set jointly and at the same time - so you can’t determine which way the effects go. For example, smoking and health: smokers tend to be less healthy, but health is not uncorrelated with the decision to smoke. This manifests as either both variables influencing each other (smoking and health) or both being determined separately by the same process - the number of firms in a market and the prices they charge are bound so closely than trying to derive causality through a regression wouldn’t make any sense. Simultaneity is a problem because it violates a key assumption in econometrics, endogeneity - basically, that observable “explanatory” variables aren’t correlated to relevant but unobservable variables. For example, running a regression of education on income might be meaningless because both how much education and how much income someone has is determined by their ability, or parental income, or whatever. This endogeneity occurs because both variables, being determined together, are correlated with both error terms - so the unobservables that explain smoking also explain health because smoking influences health, and vice versa, so neither of the two is actually exogenous.

In the case of the Phillips Curve, inflation and unemployment (or the output gap) are both determined simultaneously by the interplay of aggregate demand and aggregate supply. But even if they weren’t, and were completely separate, they’re both simultaneously stabilized by monetary policy (whether explicitly or implicitly, which is why countries without an employment mandate also don’t have a sloped Curve) in a systematic manner that keeps them both at a stable level. Regarding the Quantity Theory, say that inflation equals money growth minus output growth plus an error term. How is money supply growth determined? Precluding a Friedman K% Rule, it should be determined in response to actual economic conditions, including (most commonly) the gap between inflation and its target and the output gap. So M is chosen as a function of the other variables of the Quantity Theory - not good for statistics"!

Normally you’d solve simultaneity through “instrumental variables”, that is, choosing to replace the endogenous variable with a collection of exogenous ones that are correlated to it but not the outcomes - and specifically by using (exogenous) variables that determine only one of the two. But the problem is that there are no macroeconomic variables immune to monetary policy, even if it were possible to actually separate inflation and unemployment, or money and prices.

Conclusions

The core thing to remember about this topic is that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence, and that causation does not imply correlation. If variables are determined simultaneously by policies that aim to stabilize, it doesn’t actually matter whether or not they’re actually correlated, because their relationship will not show up in the data, both because of logic and because of empirics.

This also carries a major implication: if the Phillips Curve, or the Quantity Theory of Money, do hold empirically, it means something has gone wrong. If there is an appreciable tradeoff between inflation and slack that means the central bank has allowed there to be either too much or too little slack. Similarly, a clearly observable relationship between money and prices means that monetary policy has not systematically aimed at stabilizing prices, which would result in seemingly erratic movement of the money supply around its intended timeline. In both cases, if you see something, say something.

This also answers the question from this tweet: it’s the 1950s. 4

Sources

My posts on the Phillips Curve (which I no longer support) and the Quantity Theory of Money (which I do support)

The Phillips Curve

David Beckworth (2020), “The Stance of Monetary Policy: The NGDP Gap”

Samuelson & Solow (1960), “Analytical Aspects of Anti-Inflation Policy”

Matt Yglesias, “The NAIRU, explained”, Vox, 2014

Orphanides (2002), “Monetary Policy Rules and the Great Inflation”

Romer (2005), “Commentary on the Origins of the Great Inflation"

Lucas & Sargent (1979), “After Keynesian Macroeconomics”

The explanation

The Economist, “The Phillips curve may be broken for good”, 2017

San Francisco Fed, “Has the Wage Phillips Curve Gone Dormant?”, 2017

McLeay & Tenreryo (2019), “Optimal inflation and the identification of the Phillips Curve” (VoxEU summary here)

Econometrics

Friedman, (1970) “Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory”

I have no idea why they wrote is as non accelerating inflation instead of non inflation accelerating, which makes more sense (grammatically).

Longtime Twitter followers might know that I frequently make fun of the New Keynesians, but actually they were less wrong about the business cycle than the New Classicals.

Reaction from a friend: “one day you will answer to a god not as forgiving as us”