Somewhat recently, Paul Krugman shared an NYT column about corporate greed and inflation - making a very sophisticated case, based on a Roosevelt Institute paper, that corporate profits and corporate markups are increasing inflation. This follows the debate between Chris Conlon and Hal Singer over a Boston Fed paper about the subject from earlier this month, and the debate over Singer’s testimony to Congress earlier last month1.

Is there anything to this? Why is this such a contentious topic? The answer has nothing to do with politics, and everything to do with an overly cavalier treatment of causality in economics circles (also, a little politics).

Supply and demand walk into a bar and ask for inflation

As I’ve said numerous times before, inflation is too much money chasing too few goods. You can debate about whether the problem is too much money or too few goods until your heart’s content, but that’s the core idea. Is there currently too much money or too few goods? Yes - overly stimulative policy, both fiscal and monetary, increased demand “too much” (nominal spending is ~3% over the “neutral” level); and supply shocks, initially to industries like automobiles and then to oil and food, reduced output in many sectors, often at the same time as spending increased.

We’ll define corporate profit margins as the difference between costs and prices. Let’s ignore issues such as why margins would increase suddenly in 2021 out of nowhere after 50 or so years of growing concentration, or why markups are increasing constantly in all industries, or any other questions about the fundamentals of greedflation. How would margins react in each of the two other possible causes of inflation? It’s hard to say - it’s plausible that markups decrease or remain constant due to higher costs and prices increasing only to offset those, it’s possible demand gives companies more (or less) market power and they raise their margins one time, it’s possible the effects add up or cancel out. In theory, anything is possible.

The relationship between markups, cost, and prices is not especially straightforward. Inflation, roughly, equals both the change in markups and the change in costs. Accelerating inflation could mean both or either; one of the two growing, while inflation remains constant (more or less the case from the 80s to 2019) implies the other is falling. The increase in markups from 1980 to 2019ish implies, therefore, that costs fell - either productivity increased (which was not the case) or factor prices decreased - lower interest rates and tepid wage growth were the case, but only in the 2000s and 2010s, while the lion’s share of the rise in markups happened in the 80s and 90s. Markups therefore have to imply something about either the profit share or the elasticity of markups with the size of a business. All of this could point to efficency increasing in some larger firms. The point here is that the relationship between costs, markups, and inflation is not straightforward at all.

Let’s go back to rational expectations (obligatory post link) - the idea that people act as if they were highly familiar with the “true structure” of the economy, each other’s knowledge of it, and other such relevant factors. A key element here is that, if a change in circumstances is widely understood to be transitory, there won’t be much of a response to it, especially if changes in behavior would take longer than the duration of the original shock. For instance, a three year moratorium on pork imports because of health concern would not increase the supply of pork, since a pig takes three years to breed. In addition, companies would only consistently raise markups in nominal terms if inflation expectations were severely unanchored, since there would be a “race to the top” in terms of prices - without a clear path of where the buck stops, they might go anywhere.

In the non-unanchored cases, if companies expect supply to be only temporarily depressed or demand to be transitorily elevated, then the best response is to do nothing, rather than sink a lot of money on increasing supply and then hemorraghing money when supply goes back up and you’ve depressed your own prices (which is already happening to retailers who counted on the durable goods boom lasting forever). If this were the case, then transitory supply constrains and/or demand hikes would not result in any response from firms, as they would raise prices because of either and make transitorily higher profits because of inflation.

Impressive, very nice, let’s see the R squared

The argument isn’t really about what inflation is or what margins are, but rather, it’s about whether or not corporate profit margins are driving inflation. There’s, roughly speaking, been three major empirical treatments of this: the original Hal Singer chart, which he presented to Congress; a Boston Fed paper, and the Roosevelt Institute paper.

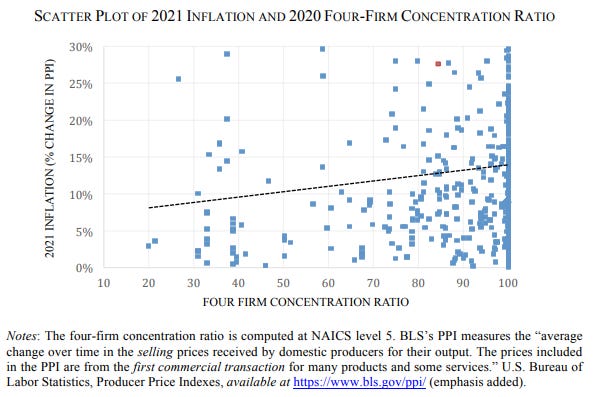

Let’s start with Hal Singer. The methodological queries are the same for all three so I’ll leave them for the end. What’s his argument? Well, inflation is so high because of collusion between companies in concentrated industries, who are exploiting the general messiness of the economy to raise prices - and consumers don’t respond “as harshly” because of inflation. This is revealed by their higher profit margins. Additionally, if you run a regression of the market share of the top four firms by sector and inflation in that same sector, there appears to be a positive correlation. How strong? Don’t ask, he’ll block you on Twitter. Plus, besides the regression, he also uses discussion of pricing power during shareholder calls as a “smoking gun”.

It’s worth asking where inflation came from if it’s not corporate greed, although to be fair it seems that the full argument is that some prices increased because of supply reasons, and that therefore other companies seized the chance to raise their profit margins. Of course, this only really makes sense if they don’t expect everyone else to raise prices. This is because, if they expected everyone to act likewise, then their real profit margins wouldn’t really change - and this is particularly true because Singer mentions that “Inflation solves [the problem of how to raise prices without pissing off consumers] by giving firms a target to hit—for example, if general inflation is seven percent, we should raise our prices by seven percent. Inflation basically provides a “focal point” that allows firms to figure out how to raise prices on consumers without communicating.” But this means that if all companies target the same focal point, all companies make the same real profit, which incentivizes deviating from that behavior by either picking lower prices (making up the lower margins with more demand), or even higher ones, sending the market into an unsustainable spiral. And it’s really worth mentioning that companies saying that they’re raising prices to their shareholders doesn’t mean anything, because as we all know no corporate executives have ever misled their investors in any way, shape, or form, ever.

What does the Boston Fed say? They say something slightly different. Their paper’s core claim isn’t that corporate profit margins have expanded because of inflation, but rather, than increases in costs have been translated to prices more than in a scenario where there wasn’t as much concentration. This is, fundamentally, a different claim from greedflation because, quite simply, the counterfactual is different: greedflation posits that, absent concentration, inflation would be basically absent from the economy; “pass through” theory, that it would have been somewhat lower. This difference points to, primarily, the claims being different at their core. Lastly, the Roosevelt Institute piece mostly ignores attributing inflation to any particular source, and instead focuses on quantifying and describing corporate markups instead. Which is not just not the same claim about the causes of inflation, it’s not a claim at all.

Nice Model, Why Don't You Back It Up With A Source?

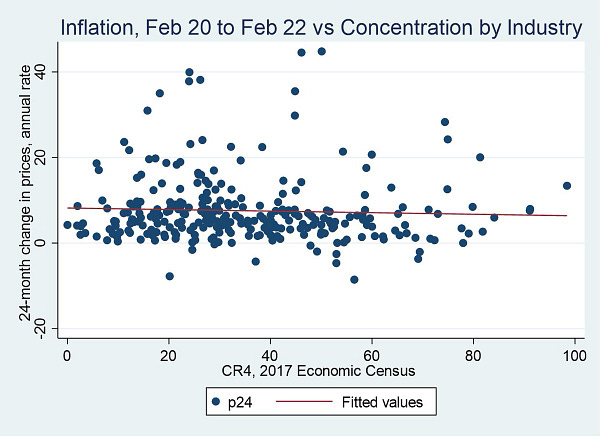

Now, the fun part: methodology. All three papers share one fundamental fatal conceit, and the claims about inflation and concentration are separate and much worse. The fatal flaw here is the data source - Compustat. The phrase “the stock market isn’t the economy” is everpresent on discussion, and yet, when it comes to corporate markups we pretend it is - Compustat uses only data for companies that trade in the S&P, which are substantially different from companies that don’t. The US Census has data for all firms in the economy, and the correlation between concentration in Compustat and the Census can be as low as 13%. If you use the latest Census data (2017), the result is… quite different

So, fundamentally, the Compustat dataset, while more recent, is also far worse than the Census data, which by now is nearly five years old. Now let’s move on to the next troublemaker: the concentration - prices regression at the heart of Singer’s claims.

Perhaps the deepest conceptual problem with concentration as a measure of market power is that it is an outcome, not an immutable core determinant of how competitive an industry or market is. The nature and intensity of industry competition combine with other supply and demand primitives to determine equilibrium concentration. However, the conditions of competition drive concentration, not vice versa. As a result, concentration is worse than just a noisy barometer of market power. Instead, we cannot even generally know which way the barometer is oriented. Even if researchers agree on a definition of the market, concentration can be associated with either less or more competition.

Syverson (2019), “Macroeconomics and Market Power: Context, Implications, and Open Questions”

The core theoretical issue here is that concentration, i.e. very few companies having a large share of a market2, and market power, i.e. companies doing bad things to consumers, are not the same thing - almost all instances of market power happen in concentrated markets, but not viceversa. The difference is in the outcomes: prices significantly above cost, lower output, lower wages, etc. For instance, the traditional Bertrand model has two companies with 50% market share each, but all variables are the same as in a perfectly competitive model. This also means that the number of competitors in an industry or their market share tells you next to nothing about the state of competition, because the number of firms competing depends on the operation of the market - in a market with fixed entry costs and no other complications, there is a limited number of firms that can enter and still make a profit. Firms enter a market until there are no profits to be made, and if they expect they won’t make any, competition will be capped. We also don’t observe why companies have a large market share - could be, for example, that large firms more efficient and sell the same good for lower, or that they have products consumers like best, or have the highest quality, or the best location, or simply luck. This adds yet another reason companies might not enter - who wants to compete with Amazon? Without observing outcomes too, you can’t say if concentration and market power are the same3.

But let’s say you want to sidestep this issue and focus on the data: can you run a regression of concentration measures on prices?4 No. The issue here is econometrics, not IO: simultaneity. Broadly speaking, simultaneity means that the dependent variable (i.e. the outcome) and (an) independent variable (i.e. the inputs) are set at the same time, so that they influence each other. This means that a core assumption of econometrics, that the inputs are not correlated to the error term (which measures unobservables, such as, say, ability) is violated. Imagine you want to run a regression of inflation on wages and some other variables (including an error term). Now, how are waged determined? Well, of course, they’re determined by productivity, education, experience, gender/race/sexuality, and other variables, which naturally include… inflation. Because of this, if you replace inflation on the first regression and shuffle terms around, you get that the error term doesn’t disappear, so your statistical analysis will always be flawed - estimators will be biased and their variance will be too small. You can replace the offending variable with what’s called an instrument, which is a variable that explains it partially but doesn’t have problems with simultaneous determination, but the thing is, there is no possible instrument for concentration5.

The broader problem here is endogeneity. You cannot run a regression of two equilibrium outcomes of the same process on each other, because there is no way there is no correlation between whichever outcome you’re using and the unobservable variables you’re supposed to consider. Supply shocks, for instance, are very obviously unobservable, and also correlated to both prices and concentration, so you cannot do a regression. Concentration is determined by supply, demand, and factors that drive them such as preferences or costs. Prices are also determined by supply, demand, and their underlying drivers. Since they are jointly determined, there is no causal relationship between each other - and any correlation you find is reason enough to alert the endogeneity police of a crime against causality.

A cause by any other name

What does it even mean for one thing to cause another? Is the way we’re talking about it even relevant to it? The most obvious place to start is “what is a cause”, and it’s a complicated question with a lot of philosophical baggage, but let’s say that X causes Y if, in a counterfactual where X wasn’t happening, Y wouldn’t be happening (ceteris paribus) or it would be happening to a significantly reduced extent.

Establishing causality in economics is very hard, compared to the natural sciences, because economists can (generally) not do controlled lab experiments. Regarding data, you could use quasi-experimental data where, because of random chance, there is a "control group” for any event you want to study, but that’s pretty rare. Therefore, you either have to use new “Credibility Revolution” techniques which, if applied properly, can sometimes establish causality directly on the data, or, you have to use theory and then test it with regressions - with the knowledge that a positive result doesn’t mean your theory is true, just not false. The problem for this latter approach is that, since your data and/or your techniques don’t get rid of endogeneity, the regressions are oftentimes much more complex and can “go” much more badly. What doesn’t, in any case, establish causality is running a regression by itself - the most obvious reason why is that the relationships between variables can change. To be fair, nobody was really doing that, but it’s worth pointing out.

So what does the specific theories being discussed say caused inflation? The greedflation theory, somewhat supported by Hal Singer, states that the true cause of inflation is corporate profit margins increasing. But even if that was the case, observing X and Y does not prove that X causes Y - correlation is not causation (especially when the correlation isn’t worth the bytes it’s printed on). Because there obviously isn’t any non-observational data here, the best we can do is try and find regressions that (don’t) disprove the theory, but once again those are an unworkable mess. So there’s not that much empirical content to examine here, though it could be done in a few years with complete census data.

But the notewrothy part is that, despite being pushed by the supporters of greedflation theory, neither the RI piece nor the Boston Fed piece say that concentration caused inflation. The Roosevelt piece mostly skirts the issue of what caused inflation, precisely because the concentration data can’t say much about it, and says that rising markups are compatible with all possibilities of higher inflation, which therefore would have policy implications for disinflation that are completely beyond the point. The Boston Fed paper goes one step further, and actually puts the causality of inflation steadily on supply/demand dynamics, and only brings up concentration insofar as it raised inflation more than in the counterfactual - but the underlying causes are extraneous to concentration. Neither is definitive, but it’s a bit asinine to claim that X causes Y using papers that are centered around Z causing Y and X making Z worse, which to the logicians out there, are not the same thing.

Conclusion

Consequently, there’s not a lot to say about market concentration, corporate profit margins, and inflation. An increase in profit margins is consistent with both excess demand, insufficient supply, and raw profiteering as causes of inflation - the latter is not a very good story, and the first two are wholly explainable as being the result of rationally expecting the durable goods boom, and/or various other supply side issues, to go away on their own. Correlations between market concentration measures or profit margins are bad gauges for the relationship due to severe issues in the data generation process, and wouldn’t prove causality anyways even if they did. Speaking of causality, a shoddy and careless treatment of the concept has led to papers that explicitly assume non-”greedy” causes for inflation to be used as proof that market concentration is causing inflation - and to the greedflationists retreating to them claiming inflation was merely worsened by greed. Holy motte and bailey Batman!

While it is clear that more competition would have allowed for a more elastic response to demand-side pressures (especially in highly protected markets, such as baby formula, or highly regulated ones like housing), it’s also not especially clear that an increase in profit margins has been a major or primary driver of inflation - particularly considering that, for an accelerating rate of markup growth (implicit in greedflation claims), then inflation expectations have to be unanchored, which is decidedly not true even at the height of the “high inflation - dovish Fed” period.

Sources

Brauning, Fillat, & Joaquim (2022), “Cost-Price Relationships in a Concentrated Economy” (aka the Boston Fed paper)

General sources

My previous post on rational expectations, plus one on causality that nobody read

Brian Albrecht, “Is Concentration Driving Inflation?”, 2022, Economic Forces

The theory

Syverson (2019), “Macroeconomics and Market Power: Context, Implications, and Open Questions”

Brian Albrecht, “Common Chicanery about Competition”, 2020, Economic Forces

The empirics

Demsetz (1972), “Industry Structure, Market Rivalry, and Public Policy”

Miller et al. (2022), “On The Misuse of Regressions of Price on the HHI in Merger Review” (this piece has more than 25 authors and I’m running out of space)

Bresnahan (1989), “Empirical Studies of Industries with Market Power”

Chris Conlon, class notes for his IO course: “Before there was New Empirical IO”

Even after blocking me for making fun of his reluctance to share the R2 of the HHI-inflation regression he presented to Congress, he can’t prevent me from looking at his tweets because I’m not logged onto Twitter on my laptop.

There’s also a minor problem of how to define a market anyways - for instance, if 50 companies divided up each US state between each other so that each is a monopoly, the largest one would have a market share of ~12%, and the four-firm ratio would be 33%. Yet every single firm in that market is a monopolist!

You could run a regression of markups on prices (which yields negative results anyways), but the problem is obviously that you don’t observe markups, so you estimate them using data that ultimately depends on… prices (and their determinants).

Note from a friend: there are cases of non-price market power that can be used as an instrument (can’t think of any simple examples). IMO, the burden of proof still remains on whoever is claiming no simultaneity, since those seem to be specific, complex cases. And testing whether an instrumental variable is “good” is a nightmare.

Great post! I especially liked the part discussing econometric principles relating to this application. For the Hal Singer plot, why not add a logistical term? Since by definition 100 is the largest value that concentration ratio can take, and there seems to be a lot of them for this plot, it doesn’t make much sense to include it with the rest of the points. Then there would be two coefficients, one for 100 four firm concentration ratio and one for the rest, which might be more accurate and descriptive than the current model which may be skewed by the 100 boundary.

The thing is economists should be able to provide solutions that don't affect poor people more than they affect the rich.

Poor people are struggling and corporate margins are rising and the solution you are offering is to make the poor struggle even more? That is a recipe for disaster and is morally questionable. Central bank independence has major advantages but this is not one.

If your politics are actively hurting one group of people more than other, then you need redistributive politics to balance things. Monetary policy don't need congress approval, but fiscal yes so here we are.