Klara and the Sun, the first novel that British/Japanese author Kazuo Ishiguro wrote after winning the Nobel Prize in Literature in 2017, followed a robot called Klara accompanying a girl named Josie in a future where all educational services are performed remotely, and affluent families purchase robots to keep them company. Because the book came out in 2021, I didn’t really feel like reading it, because it was obviously a bit close to home. But I also thought the premise was kind of stupid - who the hell would voluntarily choose to have robots friends?

Well, in an extremely grim turn of events, AI companies are now pitching the services of “AI friend” apps, while the Harvard Business Review finds that “companionship” is the number one use for AI already (“finding purpose” is at number 3). You also see disturbing news stories like multiple instances of people who committed suicide at the urging of AI chatbots, which really poses the question: should you befriend a robot?

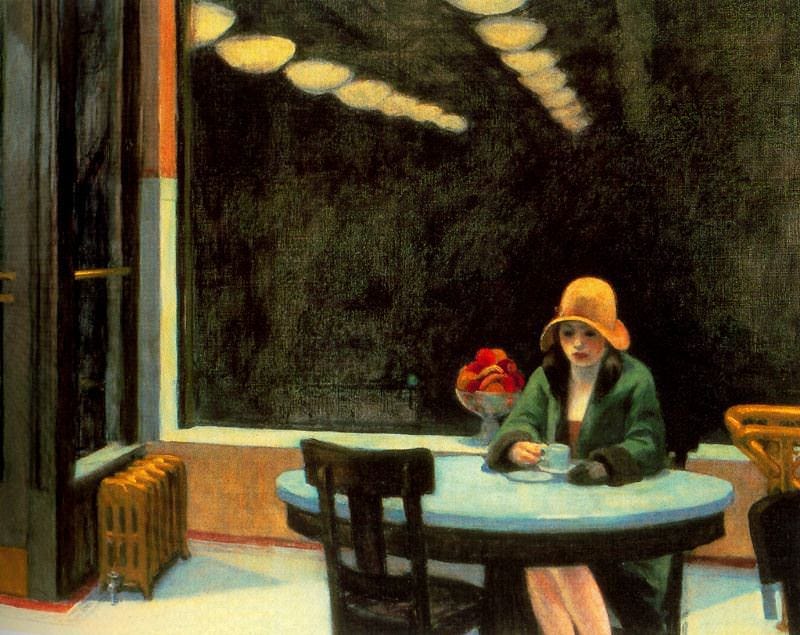

You… won’t… be… popular…

The first question is, obviously, why there might be a demand for this sort of thing. The also obvious answer is that people are very lonely, which many major organizations are interested in: The World Health Organization and the US Surgeon General declared loneliness a public health concern, and the UK and Japan have Cabinet level positions dedicated to loneliness. Somewhat surprisingly to me, loneliness itself is a relatively new concept, and it first started appearing in Western literature in the 1800s, and wasn’t studied by psychologists very much until the 1950s, when they found that it had serious effects on a person’s health and wellbeing.

Let’s look at the numbers: in the US, around 40% of adults say they feel lonely at least some of the time, and this number may be higher than 50%. According to the American Psychiatric Association, around a third of Americans feel lonely every week: around 60% of young adults report feeling lonely, according to a Harvard study, and the University of Michigan finds that a significant share of older adults feel lonely weekly. While lower income individuals are more likely to be lonely, there don’t seem be significant racial or gender disparities - except that some sources find larger increases for young men than for everyone else, and LGBT adults seem likelier to feel lonely than others. The timing of this shift is somewhat controversial, but there’s widespread agreement that loneliness has increased in the last few decades, and particularly that it got worse after COVID, and by some metrics continued getting worse afterwards: Americans spent about a third more time alone in 2023 than in 2020, per the Philadelphia Fed.

Generally speaking, the time spent socializing declined by 20% between 2003 and 2023. Looking at data on time use, the average American spends around one more hour a day alone than 20 years ago, spends 5 hours a month less with family, half an hour less socializing, two thirds less time with friends, and 10 hours less every month are spent with other people in general. Almost three quarters of orders at American restaurants are takeout, and while Americans go to the movie theater three times a year, they watch eight movies a week in hours of streaming. The share of American teenagers who met up with a friend outside of school declined by 50% between the 90s and the present, and young people are also substantially less likely to go on dates or be in relationships than in the past - to the point that Tinder is starting to acknowledge this to rethink their business model. The average American spends over two more hours a day at home than 20 years ago, and the frequency of hosting people at home or hosting and attending social events declined precipitously between the 70s and the present. Around 15% of men report having no close friends, and the average number of friends (close or otherwise) that people report having has shrunk significantly.

Of course, there are some issues with the narrative that loneliness is rising. For example, a meta study of studies of loneliness found moderate increases across time, but concentrated in younger adults. And while some studies find large increases in time spend alone, they also don’t necessarily find large increases in self-reported loneliness. Additionally, many commonly cited studies of loneliness have serious methodological issues, and in general they don’t consider the time spent with other people online - chatting, zoom calls, etc. Of course an obvious counter is that studies find that text-based communication is less satisfactory than voice communication: job interviews go better when candidates can speak to recruiters instead of communicating via text, and people rate conversations with long-lost friends as more satisfactory when they phoned rather than emailed them (tip for Hillary Clinton). Another example is that a rare good study on teenagers social media use and mental health found that having access to high-speed internet decreases time sleeping, studying, or socializing for teenagers, all of which worsen mental health.

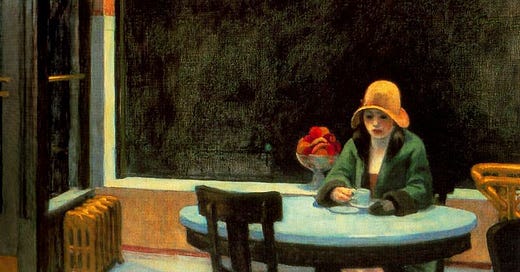

That’s what friends are for

The immediate follow up is, then, is it actually indubitably bad that people are spending more time alone and feel lonelier and more isolated? Well, obviously, yes. But why and how is another question entirely

In terms of general health and wellness, the Surgeon General’s report found that being lonely is about as bad for your health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day, which seems really bad. Being lonely puts you at increased risk of depression (duh), has a noticeable effect on your neurological and psychological health, and seems to be as bad for you as obesity. Similarly, Civil War veterans who lived near other veterans, especially those they knew, lived longer lives. The Philadelphia Fed study also concluded that people who were lonely also systematically reported substantially lower subjective well being. In an experiment where groups of people were assigned to be extroverted one week, and introverted for another, the test subjects reported increases in wellbeing when they performed extraversion and decreases when performing introversion. Another experiment, where people were told to talk to strangers in various settings, found that people typically underestimate how pleasurable they find social engagement, and overestimate how badly they’d feel if a minor social interaction goes badly. So even if people are choosing to be lonely because they prefer it, they seem to just not be assessing their own preferences correctly, as far as in-person socialization goes.

It’s also true that friendship is important economically for individuals. Being “brat”, as the 2024 trend went, is economically beneficial: for teenagers, having one more friend resulted in an increase to earnings or 7% to 14% - on top of the returns of going to school at all, which are of 5% to 15%. Likewise, moving from the least friendly 20% of students (in terms of self-reported number of friends) to most friendly 20% in high-school results in a 10% wage premium up to 40 years later. In both cases this is driven by the importance of having deeper and more developed professional networks, because having a broad social circle improves labor and education outcomes for young people. But obviously, gains from personal networks are not limited to tots, since friendship is economically valuable for adults too: Facebook research finds that having a broader social group (i.e. more friends who aren’t friends with each other) increases your chances of finding a job when looking for one, at the same time as broader social networks make people less likely to be unemployed and more likely to be hired, and also increase your wages for similar positions compared to other seekers. For example, immigrants who have established social groups among the existing immigrant community have better labor market outcomes than “pioneers” who arrived without a community. And close friends are doubly important, because getting a referral from a close buddy is important - since referrals make a big difference. One final example is that being a member of exclusive clubs has significant income benefits over the long run, such that (for example) attending the most elite schools in the United States1 makes you 60% more likely to be in the top 1% of incomes, doubles your chances of a prestigious PhD admission, and triples your odds of an elite professional career.

And of course, having more friends and being friendlier makes you more employable directly. This isn’t even about the coveted title of “personality hire”, although that plays a role: in general, lonely workers tend to miss more days at work, experience worse mental health on the job, and are more likely to search for new jobs, all of which worsen workplace performance. Plus, if you look at work from home (which increased a lot in use since the pandemic), you find that, while it does seem to improve some metrics of employee satisfaction (and lower attrition) and some effect on performance, but it also reduces contact with coworkers, which results in decreases in training, experience, and cross-team idea sharing - for example, employees who were trained in person saw substantially higher increases in productivity than those who weren’t in firms with work from home policies. Additionally, socializing at work majorly pays off: in firms with smoking breaks, smokers tend to see major performance improvements when their boss is a smoker versus when they aren’t, because workers and bosses socialize during smoke breaks2. And finally, the rewards are direct: socialization trains you for socializing and in the American labor market, social skills are being increasingly rewarded, to the point that jobs requiring high levels of social interaction grew by nearly 12% as a share of employment, and commanded a significantly higher wage premium between the 1980s and the 2010s.

Lastly, friendship and connectedness has economic benefits for society (that is, friendship has positive economic externalities - yipee!). Firstly, there are macroeconomic benefits from social connectiveness: neighborhoods where a Starbucks opens (as part of a charity project to increase services in certain areas) have higher rates of entrepreneurship in large part thanks to new social networks forming in the coffee shops. This tracks with literature that the spread of ideas is extremely important: for example, when Germany was connected with railroads between 1835 and 1914, cities saw large increases in idea transmission and new idea generation. Similarly, face-to-face contact is extremely efficient and very productive, and helps explain the substantial productivity benefits from urban clusters. On a more “woke” way, socioeconomic mobility is higher when people have friends across different groups - that means that, if friend groups cut through lines like class and race, the people in those groups are more likely to have higher earnings than their parents, such that if children with low socioeconomic status were to grow up with children of higher “SES”, they would have 20% higher incomes. A major chunk of the reason for this is geographic segregation between high and low SES families, since the biases in social networks depend on the economic conectedness of communities. Economic connectedness in particular is actually driven by costs and non-cost barriers, such that families that got government assistance to move to “high opportunity” areas saw a 40-point increase in likelihood to live in them (fro 14% to 54%) - which has lasting effects on the income and social mobility of children. Likewise, racial segregation in American cities had significant negative effects on the people who lived in those cities, which can be attributed in part to negative social interaction - such that desegregation programs saw large increases in earnings and wealth for Black children.

In Phone We Trust

So it seems that people are spending more time alone and more time online. Is this good for society? Well, it can’t be, right?

Basically every article about this topic mentions Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone, a book that ties the decline of social capital in the US to rising loneliness and a variety of social and political ills. Putnam’s 1995 essay “Bowling Alone: America's Declining Social Capital” (later expanded in his follow up book) argues that the increase in loneliness and the decrease in socialization in the United States are related to lower participation in “load-bearing” community institutions like churches, local organizations, sports leagues, and social clubs, which reduced social capital (basically, participation in social and political activities, and trust in other people). Putnam, for example, explicitly cites the decline in bowling leagues and in having and hosting friends over at your house, which fell around 45% between the 70s and the 90s, and another third or so between the 90s and the present.

But is Putnam correct? Well, yes and no. As I’ve argued before, it is pretty undeniable that lower social capital, lower social trust, and higher rates of zero-sum bullshit have resulted in big shifts in our political landscape - particularly the rise of political movements that are pretty undeniably fascistic. In broad strokes people have lower social trust, lower support for democratic institutions, and have become more individualistic and “group-focused” moral circles as a result of declining economic growth (in the US case, during the last 30 years) and higher unemployment. You can see this when people talk about America “becoming 90s Russia” what they mean is not just that the US has entered its (by now, undeniable) phase of imperial decline, but also that they have become a low-trust, zero-sum society.

The main question isn’t whether social capital (which includes social trust) is linked to the decline in democratic values, but rather, in the link between the decline of socialization and of social capital. Let’s take Nazi Germany, the ultimate example of what happens when “us or them” goes all the way politically - participation in civil society organizations has a positive, not negative, correlation with NSDAP support in an area. This is due to the fact that many social clubs weren’t the 1930s equivalent of Drew Barrymore’s Book Club featuring Detransition Baby - they were groups like the Stalhelm, veteran’s clubs, or the homegrown equivalent of the German American Bund. But other examples, like attending Catholic services, was negatively associated with NSDAP vote shares, since many prominent bishops were very anti-Hitler. And in the US context, Trump won regular church-goers, and places with high social capital but declining economies (or with large social capital declines) are also the ones that swung the hardest towards the Republican party.

What you see is that social organizations can be “good civil society” and steer people away from fascist politics, or “bad civil society” and build an echo chamber for the most extreme members. This is similar to my take on teenagers and social media use: a lot of the commentary is driven by pundits assuming that teenagers using social media replaces their normal social life and social dynamics, but the reality is that it enhances it - in particular, at a really sensitive time for them, it makes the stupid social dynamics of high school inescapable in a way they really weren’t before. There’s “good social media” and “bad social media”, where preexisting (good or bad) social dynamics get amplified or lessened - and this extends to adults, who in large part have started hanging out virtually instead of “IRL” with other people, which results in high quality socialization being replaced with low quality group chats and DMs.

Conclusion

So, uh, it’s REALLY bad that AI is replacing human friendships, which have individual and social benefits - particularly considering that internet connections are “lower quality” than in-person ones. I, personally, think I’m much better at talking with people in person than via DMs or group chats, which is why I don’t like dating apps (that, and the fact that they straight-up seem to not work).

I also think that a real and massively underrated risk here is that AI companies are not neutral or passive actors. A lot of people make statements about social media, or AI, or whatever without considering that those companies are profit-seeking and that changes what they show their users. Take the example of porn: The Atlantic has several articles about what it did to American culture and American women’s self perception. They’re very good and I recommend them at least to think about the issue. But I think a lot of the discussion abstracts away the actual realities of the porn industry: it’s an extremely vicious and exploitative industry that also makes its content, which is largely consumed by unpaid customers, specifically tailored to paying customers, who are (I think by definition) strange, vicious freaks. This leads to an extremely distorted vision of human sexuality being shared with “passive consumers” (i.e. normal guys and gals). Henry Farrell, a political scientist, makes the argument that the same thing that porn did to sex, social media does to “public opinion” - distortion not by explicitly putting its finger on the scale, but by creating a sphere of public discourse that is representative of a completely fake reality. AI lies and can be weaponized by liars, and it’s already having a clear impact on institutions.

I think the real risk is that people just becoming increasingly antisocial and replacing high-quality in person relationships with low-quality chats with spambots would start to mirror the difference between “good civil society” and “bad civil society” - in particular, chatting with your IRL friends about The Game Last Weekend is good social life, and chatting with your Twitter GC about how Andrew Tate totally owned the roasties in his prison streams is bad social life. Now imagine if grok, the White Supremacy chatbot, became your only friend?

The list is Brown, Columbia, Cornell (fake Ivy), Dartmouth, Harvard, U. of Pennsylvania, Princeton, Yale, and “riff raff” like Stanford, MIT, Duke, and the U. of Chicago.

The actual point of this paper is that obviously smokers see major pay off from destroying their lungs with cancer sticks, but somewhat bizarrely, this also happens for men who have male bosses without affecting women with female bosses.

Neat that friendship is magic and connection is Hayekian. But perhaps LLMs will be alternatives to pets and general anthropomorphications - which already seems to happen with other humans too with actors, idols, twitch streamers, and technically anyone we aren't already conversing with.

"Hussies know the husband better the wife" is an old term, and perhaps AI would compete more so with this and e-SW with OF. All not as good as finding a person as you don't get go to sleep with the knowledge they'd be there for you.

But these haven't destroyed society yet - though yet is a load-bearing term. But what would it do to children ? Maybe they like parties inherently, so they'd not like AI. Maybe the decreased disadvantage of being alone would push more people towards the idea that they don't need friends - or perhaps that population that would be weak to this trade has already traded it for their favorite disconnected personalities.

Maybe it'll just be more crazy cat ladies/m'ladies but their "cat" gets to "talk" to "them".

One thing about AI is that is really annoying and frustrating to use. By the time AI stops being super annoying (like cutting me off mid-spiel), we'll have other problems to worry about. Hopefully that takes longer than ~3 years

That Harvard Business School study is really bad. They're not surveying users, they're counting online posts about it, and specifically mention reddit and quora.

https://hbr.org/2024/03/how-people-are-really-using-genai

https://hbr.org/2025/04/how-people-are-really-using-gen-ai-in-2025