To be from the left means to know that the Third World’s issues are closer to us than our neighborhood’s issues.

Gilles Deleuze

The Catholic Church elected a new Pope recently: Pope Leo XIV (the fourteenth), originally Robert Prevost of the United States (and Peru). The pick came as a shock to everyone because, well, nobody knew who he was - except that he’s from Chicago (and Chiclayo), which lent itself to a lot of comedic comments. From what I gather he’s a somewhat progressive figure in the mold of Pope Francis, but not a big boat shaker and much more consensus-minded - that means he’s (as his unearthed tweets show) conservative on issues of gender, but also pro immigration, “economically left wing” (whatever that means for the Bishop of Rome), and very focused on climate change.

Many people, contrarily, are either celebrating or melting down on the internet over having a “woke Pope”. Others are noting his relative conservatism on other issues. Why is the Church’s ideology so hard to pin down?

Worth noting that, while I’m as informed as a normal person can be about Catholicism, I’m not actually a Catholic. I’m Jewish.

In God We Trust

In Greek, “catholic” means “universal” - so the Catholic Church, in the most literal sense, is the universal church. This means that, to be a Catholic, you have to be committed to a sort of “universal morality” - the idea that there is a singular set of moral precepts that apply to all people equally. Obviously, exactly what this means is contentious - there are deep distinctions within the Curia (the Vatican1 government) over a variety of issues, which range from LGBT and women’s rights to things like “synodality” (the notion that different sub-churches can have different practices), various aspects of Catholic doctrine, and economic and migration issues.

Over Pope Francis’s papacy, he undertook significant reforms to the Church to move it in a way that he believed honored its moral commitments, with changes to the Church’s organization and priorities, some changes to Church doctrine, and more “tolerance” towards differences in practices across the Church. I don’t especially want to talk about the practical merits and demerits of this approach2 (mostly because I don’t think anyone, including me, wants to know what the Dicastery for the Evangelization of Peoples is), but the long and short of it is that, under Pope Francis, the Church did swing “left” in certain ways, particularly with a bigger emphasis on poverty, immigration, and climate change . This was, to some extent driven by the fact that Latin America, Africa, and Southeast Asia are the biggest “turfs” for Catholicism, not Europe and the United States, and that the Church lost a lot of credibility and influence after the sexual assault scandal, but there were also doctrinal and ideological shifts in the institution over the last 12 years.

But even if there is disunity among the Church’s ranks on social issues amidst an ideological shift, the truth is that the commitment to universal values of some form remains. The church exhibits what a study by authors Adam Waytz, Ravi Iyer, Liane Young, Jonathan Haidt (yes, that one) & Jesse Graham calls a universal or “wider” moral circle: it encompasses more people than just the immediate circle of “family, kin, and community that Vice President JD Vance referred to (in a dispute about Catholicism. For which the current Pope rebuked him on Twitter).

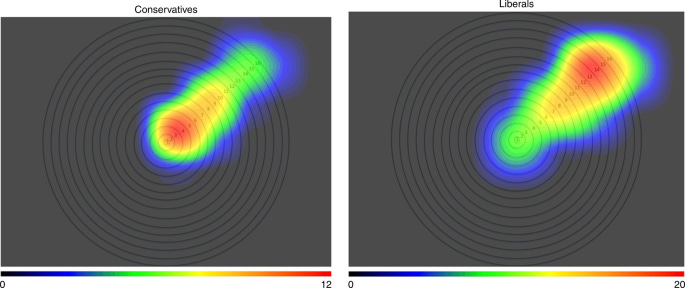

Moral universalism, in particular, refers to the extent to which people are altruistic towards members of “other groups” (other races, other nationalities, etc.) in the same way as members of their group. For most people, trust is proportional to “distance”, that is, how different they are to them - people with low want to spend less to help others who are different and/or distant, and want to spend more in separating themselves from the Other. This explains, for instance, unfavorable attitudes by moral particularists towards immigration, trade, environmental protection, or foreign aid - but not redistribution, at least not if it’s implemented in a more impersonal, centralized way. For example, in the US, areas with higher scores of moral universalism donate roughly as much to charity as those with low universalism scores, but donate to a broader array of causes that are less likely to be local, and these areas are also likelier to vote Democratic, and their elected representatives are likelier to support liberal causes. In fact, the link between moral universalism and left wing politics is observable regardless of what measurement is used, at which level of aggregation, whether we look at voting record or issue positions, or which country(ies) one looks at - that is to say, it’s a very strong relationship.

You might be thinking that moral universalism is related to another pet topic of mine, social trust. As a refresher, social trust is the confidence in fair treatment from other people (who one does not personally know), from government, and from other “impersonal” institutions like the police and education system. A related value is the non-zero-sum mindset: basically, a belief that life is not so competitive that win-win outcomes aren’t possible. Well, the two are closely connected to moral universalism - in particular, individuals with higher social trust also exhibit zero-sum mindsets at lower levels, and individuals who score high on moral universalism also score high on both social trust and non-zero-sum viewpoints. Exactly why is not that clear, but the major explanations I’d find is that all three value systems have the same causes, plus that people try to develop morally consistent constellations of values and beliefs - so, for example, someone who wants to care about others believes trade is mutually beneficial, while someone who is more parochial in their moral circle does not.

Of course, moral universalism is not really a one-size-fits-all type of issue - for example, it’s very dependent on religious, ethnic, and social institutions. In this case, the Catholic Church is a clear example of what kind of impact institutions can have on values. One of the key pillars of moral particularism is the notion that “kin groups” (basically extended family relations - think like, caveman clans. Or small towns) mattering the most, which has huge downstream effects on values and attitudes - groups with “tight kinship” enforce communal values through social policing and appeals to group authority, while groups with “loose kinship” enforce them with more universal-minded appeals to higher, common values. In particular “revenge-taking” seems to be a crucial pillar of these more closely-knit societies, which results in what’s known as a “culture of honor” - which are themselves characterized by lower social trust, as seen in for example the practice of female genital mutilation (as a way to restrict women’s promiscuity). In the US, values of “rugged individualism” combine some degree of personal libertarianism with strong strains of moral particularism, and these are associated with a persistent “frontier culture” (that is, Scots-Irish culture) and with very specific, strong, and persistent norms around gender and masculinity.

The reason why I dwell on these societies so much is because one of the reasons why the “Western” world does not have these sorts of social relations is, in part, the Catholic Church itself: Catholicism created a framework where people had to interact under the auspices of a greater, join purpose, forcing a shift towards looser forms of kinship organized around the Christian faith. This meant that the longer countries were influenced by Catholicism, the greater the moral universalist underpinnings of their societies. This manifested itself in social norms such as markedly lower rates of cousin marriage, which in the US context resulted in increases of geographic mobility and thus in economic development. Similarly, when missionaries convert African people into Christianity, those people see persistent shifts in their beliefs and values - via transmission of social norms across generations .

However, the Catholic church isn’t all cookies and cream. Despite initial misgivings about the practices, the Church ended up endorsing colonialism and slavery in Latin America and Africa under the pretext that it would help convert those people into Christianity, which had substantial consequences: in particular, in Africa, the descendants of those exposed to the slave trade have markedly lower trust in the government and in others, and people with ancestral experiences of slavery and violence have higher rates of zero-sum mentality (just like people who experience discrimination have lower social trust). Additionally, the Church can occasionally experience bouts of obscurantism: the Counter-Reformation, for instance, sought to impose uniformity of belief with violence, resulting in economic and scientific backwardness, as well as decreased fertility and increased rates of secularism.

Why people develop these “prosocial” systems of beliefs is a bit of a mystery, but the most convincing explanation to me is that it’s material and economic factors - after all, I don’t run an anthropology blog. In particular, systems of belief are transmitted across and between social groups and generations such that they reinforce communal values of production - basically, if you run a small band of hunter-gatherers, you need very tight kinship norms for the group to survive, and if you run a bustling mercantile exchange, you need looser ones. The more labor required to produce food in ancient times, the more “individualistic” (which is used somewhat similarly to universalist, somewhat confusingly) a society is, so societies that need a lot of farm labor are more “collectivistic”, that is, put the benefit of the group above all. These societies are also straight-up more hierarchical, having much more rigid and patriarchal gender roles. It doesn’t take a genius to see that societies that need more labor for agriculture are also poorer, since the agricultural share of labor falls as societies develop via the appearance of specialized labor - which means that, as I wrote about social trust, these “universalist” value systems emerge in richer societies. For instance, zero-sum values are more common across those who grew up in recessions, and people exposed to unemployment have lower social trust; in Brazil, when trade liberalization left many industrial workers unemployed, they joined pentecostal churches at higher rates, reuslting in substantially higher hard-right vote shares in future elections. And the most universalist belief system of all, democracy, is also strongest when it produces economic prosperity, and weakest when it does not. This dynamic, as I recently wrote for Vox, also extends to gender politics and has an interesting gender dimension that’s a bit beyond the point here.

Ordo amoris?

But how does this explain the political leanings of the Catholic Church today? Well, the first thing to consider is that, since the sexual abuse crisis was unveiled, the Church has hemorraghed believers, and has suffered financially due to its prestige loss. Surprisingly, in many countries the destination of those people has not been atheism, but rather Pentecostalism and other forms of evangelical Christianity, which is much more conservative politically and has a different value composition. Importantly, moral beliefs are “luxuries”, which means that poorer conservatives tend to put more of a premium on economic alleviation than on moral particularism - which means that the Church’s pivot towards left-wing economic issues makes sense as a way to regain ground relative to the pare de sufrir set: for example, in the US the funds the Catholic Church lost from the sex abuse crisis went to secular charities and boosted the Democratic Party due to its support for redistribution.

But I think the real shift has not been in the Church, but rather in what “conservatism” (or, more accurately, right-of-center politics) is. As I’ve previously said, over the last decade (but especially post COVID) there has been a global political realignment of the left/right axis, which is (in my view) polarized between cosmopolitan versus nativist on the cultural axis, and high and low social trust on the other - for example, opinions on COVID policy were driven by social trust, and not by a standard left/right ideology, and countries with lower approval ratings on COVID management also have lower support for democracy. In this sense, the fact that the the “economically anxious” working class has cozied up to the hard right, while the high education “Brahmins” have Gone Woke means that, because the two groups have differing levels of moral universalism, social trust, and zero-sum views, the two political movements are sharply diverging on underlying values and beliefs. In the US case, Trump voters have lower social capital (which is highly correlated to social trust), higher rates of agreement with zero-sum statements, and starkly higher agreement with moral particularist judgments.

This was largely due to economics: the main determinants of (as previously mentioned) social trust, zero sum mentality, and moral universalism, as well as support for forces such as democracy and open markets are economic conditions during the “critical decade”, which for current electorates are largely the era of low demand post-globalization and particularly post-Great Recession. However, not all is lost for either liberal democracy or the Catholic Church: broadly, people seem to care more about their economic self-interest than about more abstract moral values. While low-income moral conservatives shifted right politically, they’re still amenable to left-wing economics during hard times, and while more prosocial individuals support redistirbution at higher rates, very mistrustful individuals do too, mainly because resentment is a key driver of both social trust and distributional preferences.

Conclusion

So, all in all, it seems that Catholicism is becoming less “right wing coded” - in large part because of its economic positions. But it’s also especially important to note that right-wing politics are themselves increasingly “antisocial”: the social backbone of modern “conservatism” (which seems to destroy everything rather than conserve anything) appears to be distrust of institutions, distrust of others, distrust of government, and resentful, “fuck you got mine” moral intuitions. The sociologist Ferdinand Tonnies coined the term “Gessellschaft” to refer to the impersonal rule of institutions, norms, and formal rules, as opposed to the “Gemeinschaft” of kinship and tradition; political polarization appears to have aligned the former with the left and the latter with the right, and Catholicism is if anything an antiquated form of gessellschaft - it is the institution for the faithful, making demands for trust in others and universal (if flawed) moral judgments. If current political divisions continue, it’s not impossible that the alignment between most forms of organized religion and left wing politics will continue as well.

Also, in honor of the late Pope Francis, I’m sharing this genuinely incredible sketch after his election was announced:

One of the most confusing parts of all of this is what exactly is the difference between the Vatican City, the Holy See, and the Church. The Vatican is a small section of Rome owned and controlled by the Church. The Holy See is just a term for the Church in some legal contexts (for example, in the UN). I’ll use the three interchangeably to be less repetitive.

The closest analogy is Starbase, Texas, aka Elon Musk’s Fordlandia: if Starbase elects Musk as its mayor, he would both be the head of his various companies and the ruler of Starbase, in the way that the Pope is both the ruler of the Vatican and the head of the Church.

Worth noting that “we have to acommodate different perspectives on life within a common moral and political framework” is also exactly what liberal philosopher Will Kymlicka (he goes by the nickname because he’s Canadian) thinks we should do with minority rights. The obvious issue is that “is there a right for Muslims to wear religious attire in secular instiutions but without a right to be homophobic” is a pretty complicated question.

You cite the Scots-Irish values paper as explaining US (particularly Southern US) honour code/zero sum politics. This is commonly done in US economics blogs (e.g. Noahpinion has mentioned this a few times). I find the casual acceptance of the paper quite odd. After all, it seems fairly obvious that neither Scotland nor Ireland reflect the views that the paper tries to explain (and which, presumably, have a somewhat higher proportion of Scots/Irish ancestors and cultural values). Usually there is some vigorous handwaving about the frontier at this stage, but it is also the case that Australia, Canada, and New Zealand had both a frontier environment similar to the US and extensive Scots/Irish immigration. In fact, Scottish immigrants would make up a much larger proportion of New Zealand's migrant base than they would for the US (clue: New Zealand's largest city in the 1860s was named after Edinburgh, but given the Scots-gaelic version of the name - Dunedin as the colonists weren't having any truck with English values). Looking across Australia/Canada/NZ the US southern value system is missing as is the strong US individualist ethic (there are a bunch of papers looking at NZ and Australia focusing on the fact that where US political language in the 19th century tends to focus on liberty, NZ and Australia's tends to focus on "fairness" or "a fair go".

I worry that explanations of the different US value systems tend to look only within the US for evidence...

To be clear, Catholics don't espouse just any moral universalism, but a specific morality that is universal.

Is there a coherent alternative to moral universalism? Some people try to be moral relativists, but it doesn't really make sense.

Obviously some moral issues are context dependent, "relative" in that sense. Politeness means different things in different places. But the deep principles are universal and everyone knows it deep down.

As CS Lewis said, there is no culture where you'd feel proud to have double crossed all those who were nicest to you.