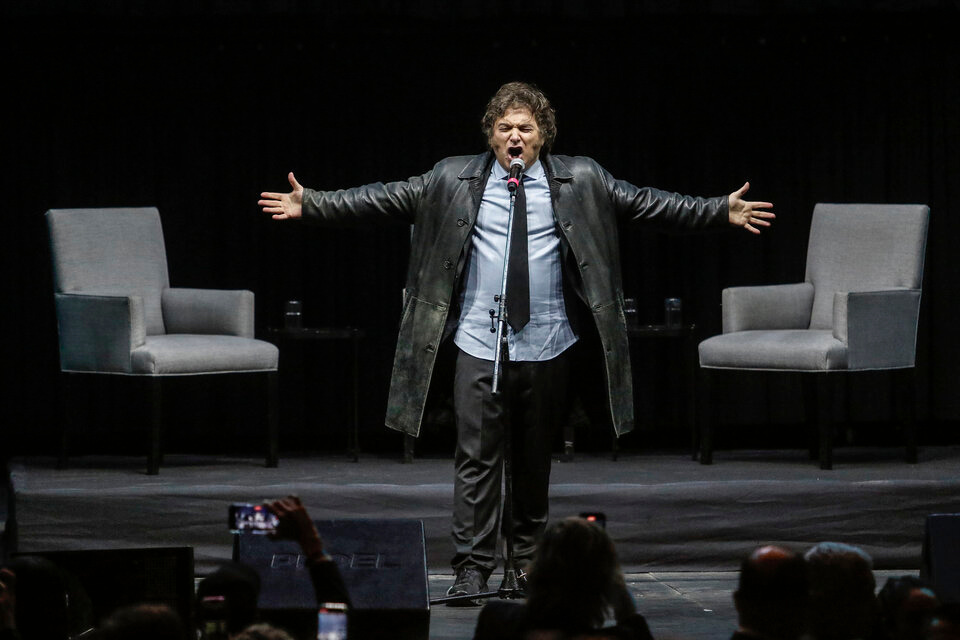

Javier Milei, a deeply strange libertarian and proud dog dad, has been Argentina’s President for five or so months. He bookended his fifth month in office by performing a song called Panic Show (lol) at the Luna Park theater while launching his latest book. Much like the President owns five dogs1 with whom he (allegedly) telepathically communicates, his presidency has had four areas of (varied) success: politics, inflation, monetary issues, and economic activity. This is of course an arbitrary distinction, but many things are.

How the sausage didn’t get made

Let’s start with politics, by far Milei’s least successful area of action. The government has submitted twice over (in February, and earlier in May) a bill to Congress that would slash spending, raise taxes, and mostly reform the economy through deregulation, privatizations, and a variety of other light-touch items.

The first time around, the bill still ended in defeat rather embarassingly even after a series of tweaks and endless concessions to moderate parties, with a series of provincial parties withdrawing their support at the last minute over a very arcane disagreement involving oil regulations and fishing duties. The authorities also faced a second, unrelated defeat in the Senate, where the government’s deregulation decree got voted down by a sizeable majority of the chamber, and large chunks of the decree itself are still held up by the courts. Most recently, the government suspended its much touched Pact with the governors, which would have made everyone promise to reduce spending and taxes and deregulate the economy, but which fell through for unknown reasons after zero concrete details had ever been unveiled.

This month, however, Milei’s congressional fortunes may have begun to shift, with an even more watered down version of his reforms passing the House of Deputies and moving to the Senate, alongside a “fiscal measures” bill that contains some, well, fiscal measures. Now the “Bases” Bill heads to the Senate, where the opposition has 33 seats (out of 37 needed for a majority), and the government and its close allies hold only 13 - the rest come from a mixture of “moderates” and parochial provincial parties.

The bill, as far as today, contains a (very small) set of emergency powers, (limited) ability to unilaterally reform the state and reduce its staffing levels, a (very narrow) set of authorized privatizations, a (very moderate) labor reform, (mild) changes to the tax code and to pension laws, and a (very narrowly delineated) set of deregulation provisions. It will be a good signal for his capacity to govern and reform the country if Milei manages to get one legislative accomplishment, particularly since “reforms may be immediately undone if the government changes” is always a real concern here. In this sense, the President’s personal popularity (which has declined since December, largely because of negative economic conditions) will have to be replaced by “actual policymaking accomplishments” if he wants to use politics as one anchor in his macroeconomic program, which is still (at least publicly) nonexistent.

Last time I wrote about Argentina, I mentioned that stabilization (i.e. reducing extremely high inflation rates) programs tends to have four main planks: adjustment of major macroeconomic imbalances (monetary, fiscal, external), some manner of coordination mechanism for price expectations, some mechanism to preserve government credibility, and some form of mechanism to generate buy-in from society, especially labor unions.

A credible mechanism to preserve credibility (tautological much) could be a series of cross-party political consensuses (apparently it’s not consensa?) about retaining the TBD part of macroeconomic stability. However, the popularity bit is, so far, completely absent, although he has signalled an unwilligness to cut nominal welfare payments as some sort of olive branch to the poor and pensioners, and has negotiated with unions to cut his labor reform bill short. Additionally, and I’ll return to this later, he’s also moving towards alleviating the recession with laxer fiscal and monetary policy, which is beneficial for his popularity but verboten for macroeconomic stabilization.

Government Ozempic

To be fair, the government has shored up its credibility by actually making progress in the fiscal realm: the country went from having a budget deficit of 2.9% of GDP (primary) in 2023, and of 6.0% considering interests, to a cumulative primary surplus of 0.7% in the first four months of 2024, and a financial (post-interests) surplus of 0.2%. This general direction of fiscal policy appears to be adequate, with a caveat: Argentina is planning on reducing the deficit by 5.2% of GDP in 2024, which is unprecedentedly large for the international experience and which would translate into around a -3.8% drop in GDP.

The austerity plan, however, has one major flaw: the cutbacks weren’t actually achieved by actually decreasing spending sources with real heft, but instead, mainly through higher income from foreign-trade linked tax revenue and lower inflation-adjusted spending on welfare, wages, and subsidies. As a result, the surplus appears to be extremely brittle, and will probably be short-lived.

In detail, basically all sources of revenue tied to consumer spending (domestic VAT, fuel, other internal taxes), wages (income tax, social security taxes), or wealth (personal assets tax) fell significantly in inflation-adjusted terms, while there was a large offset to that lost revenue from taxes linked to imports (import tariffs, customs-related VAT), exports (export taxes), or USD transactions (the very complicated PAIS Tax).

On the spending side of things, basically all of the speding adjustment was accomplished through a 30% inflation-adjusted cut in pensions and welfare payments, as well as large one-time cuts to federal infrastructure spending and transfers to provinces. Meanwhile, the government has postponed cuts in subsidies to electricity and heating (big ticket items) repeatedly since February. This issue is rather convoluted because the government has postponed utility hikes and postponed fuel tax adjustments for months, but hasn’t actually paid for the subsidies involved, and instead just told the heating and electricity payments regulator to suck it up and has repeatedly promised to pay at a later date. The primary aim of this move is very clearly to preserve the administration’s popularity and to compress short-term inflation, which is possible due to the superficially good fiscal panorama.

The conjunction of these (primarily transitory) factors is unlikely to keep carrying the government’s finances on its back, due to declining inflation, real FX rate appreciation (more on this later), and prior commitments with the IMF that mandate getting rid of export taxes and currency controls - including eventually eliminating the PAIS Tax, which has been growing at least 300% above inflation so far this year.

Cuts only

Monetary policy has been rather messy: the Central Bank has slashed rates five times in the Milei Era, from 133% to just 40% lastweek - well below expected monthly inflation, obviously.

The rationale is not some crazy heterodox scheme (well, not one of those heterodox schemes at least), but rather particularly hardline “monetarist” stuff: the Central Bank had been lending enormous amounts of money to the public sector during the 2020-2023 period, which it cancelled out by selling bonds to banks, which it was then paying off by printing more money. This set up an unsustainable dynamic where higher rates resulted in higher inflation, seemingly paradoxically, because they raised the quasifiscal deficit (i.e., the consolidated Treasury + Central Bank deficit) - which was, according to Milei, 15% of GDP, or as high as during the pandemic.

Reducing rates, alongside a sharp fiscal correction and an increase in inflation, has allowed Milei’s central banker to drastically reduce the amount of currency they issue, which (so far) has mostly come from purchasing US dollars from exporters and buying back government bonds (to reduce net public sector liabilities). Nonetheless, this drastic decline in the amount of currency in circulation has also worsened the ongoing recession. Plus, the improvements in the Central Bank’s balance sheet have been mirrored by an increase in Treasury debt, which has taken the opportunity from low bank rates to secure cheap loans from the private sector.

These persistent rate cuts mean that the policy rate will remain negative until basically the end of the year, and deeply negative rates will be extremely damaging to any disinflation program - you want people to hold more, not less, pesos. This is compounded by the idea that low rates will permit an expansion of credit and thus an economic recovery, which would mean an extremely unstable, 1980s type of economic program - a time when partial fiscal “prudence” and ensuing disinflationary success were undone by extremely reckless credit allocation decisions by the Central Bank and the state-owned banking system. Finances matter, people!

Priced possession

Milei’s main claim to success comes from his disinflationary agenda: right before he took office, monthly inflation was in the double-digit range, with November’s CPI print being 12.8% headline and with a 13.4% core CPI component. At the same time, a large number of prices were under government controls, and the real exchange rate was at a six-year low. His solution was a one-time shock, which is rather common in “orthodox” stabilization plans: have all prices catch up with each other, then take the time during which they catch up (around 6 months) to cut off Central Bank financing of the deficit and develop a stabilization program.

Milei’s shock approach was quite textbook: his first action was to devalue the peso by 118%, taking the exchange rate from ~$365 pesos per dollar to $800; afterwards, the currency would only be devalued by 2% a month. He also rapidly deregulated the prices of housing, healthcare premiums, telecommunications services, fuels, and increased fees for public transportation and utilities.

This program plunged the country into a quite virulent recession, with annual forecasts in the -3.5% to -4% range: construction, retail, and manufacturing have all seen substantial declines in all available indicators. In the first quarter, real GDP fell around 5.6% versus 2023, driven by deep declines in domestic output: construction activity dropped by around 30% versus 2023, while retail sales fell 22%, and industrial production shrank by 9% or so. This has helped inflation come down, since (per very coarse Quantity Theory of Money), a worse recession + monetary contraction = lower inflation. Simply put, people don’t have any money to spend.

This “Chainsaw plan” has also been quite successful at reducing inflation nonetheless. Initially, the shock was expected to raise prices to up to 30% a month in December, followed by 27% in January, 20% in February, 15% in March, and double-digit prints until June or July. However, the initial inflation shock was 25.5%, and was followed not by a slow, gradual reduction in monthly price growth, but with a faster and faster decline: to 20.6% in January (vs 21-22% expected), 13.2% in February (vs 18% and 15%), 11% in March (vs 14% and 12.5%), and 8.8% in April (vs ~10%). What’s more, core inflation declined even faster, from 28.3% in December to 20.2% in January to 12.3% in February, 9.4% in March, and finally 6.3% in April.

Inflation is expected to continue falling in MoM terms for the rest of the year, particularly since the government has delayed the major accelerant of relative price adjustments: private healthcare premiums have been reduced by decree (somewhat puzzlingly), and utility hikes of 100% in water services and electricity, as well as 400% in heating, have been repeatedly postponed since February. This delay, then, means larger adjustments down the road (to catch up with at least six months of cumulatively high inflation), which would be potentially destabilizing if paired with other large shocks.

The million dollar question

The major shock in question could be another exchange rate devaluation: the peso/dollar parity has grown 2% a month this year, and around 11% versus November, compared to >60% price growth. This crawl has meant that the exchange rate is 45% down in real terms compared to immediately after its December devaluation (of 118%), and the real multilateral exchange rate is already back to its (sans December) 2023 average.

This means that, at some point, the devaluation rate has to go up, with one of two options being discussed in the econosphere: first, a gradual slide into a higher monthly devaluation rate, that would exceed inflation eventually. The alternative is another sharp one-time jump, plus a more sustainable crawl afterwards - which would sharply increase inflation relative to the alternative, but preserve a higher real exchange rate. The issue is that, at the moment, the government seems unlikely to choose either alternative, and is consistently delaying going higher than 2% - it turns out Milei’s nominal anchor for the economy is, simply, a pegged exchange rate. Market expectations of a devaluation have decreased significantly, from around 7% per month in March to around 3% now, which means that a progressive exit from the 2% crawl is expected but not anytime soon. The parallel FX market, meanwhile, has reacted quite badly to monetary policy decisions, with the gap between official and unofficial rates growing from the 20% range to the 40% range over the last week (in numbers, from around $1.000 to $1.200, compared to an official rate at $890).

In spite of the growing FX overvaluation (which is not currently at problematic rates, but is getting there), the government has been able to increase its international reserves, which have grown by USD 10 billion since Milei took office, which has allowed for the Central Bank to go from having net (i.e. available) reserves of -12 billion to a moderately positive balance (under a billion) in mid to late April, and to a low negative balance after some payments to the IMF. This progress would be threatened by an overvalued FX rate, since it would make exporting costly.

This decision puts together all the major macroeconomic issues facing Milei: maintaining the crawl lower inflation faster, but harms the exporting sector (which is surging) - both worsening the recession (exports are serving as a cushion for the economic downturn) and the Central Bank external balance. Meanwhile, changing course gradually would notch up inflation, and not change the recession much, but allow for progress in other areas of policy - namely, Central Bank reserves. And a large, sudden shock would be the worst option for both inflation and output, but most beneficial for the external sector balance (more recession = lower imports).

Conclusion

Milei has, so far, taken initial steps in the right direction to reform policy and improve the fiscal and monetary situation - but has not developed anything resembling an actual plan to do so, which means that we’re all stuck guessing

The main problem is that there are several not particularly large but still urgent inconsistencies in his current policies between low rates, a low crawl, price deregulation, and a desire for a smaller recession. Thus, it is becoming possible that he simply does not manage to resolve any of them, and his eventual macroeconomic program simply fails under pressure like the 2017-18 Macri plan - in Macri’s case, his policies failed due to inconsistencies between tight monetary policy and loose fiscal policy; in Milei’s case, the contradiction is precisely the opposite.

In addition, there’s an economic recovery expected for sometime in the second half of the year or so, which means real wages will recover too - pushing up prices and costs, and setting up a delicate balance between real wage recovery and disinflation that needs the proper macroeconomic stabilization program we don’t have to work out.

Hopefully he comes up with a sustainable and workable program, because God knows what the country will vote for if he doesn’t. Communism, perhaps?

In a rare case of Argentinian/American discourse continuity, there are allegations of dog killing going around: the dogs in question have not been seen publicly, or in pictures, more or less since Milei took office, and their location is unknown. It’s also not clear that one of his dogs was a fifth clone of Conan or if he simply continued referring to the late Conan in the present tense, which is adding major Shirley Jackson vibes to the whole ordeal.