Some thoughts: overpopulation

Climate change has made overpopulation fears come back. They're still racist nonsense.

“We will suppose the means of subsistence in any country just equal to the easy support of its inhabitants. The constant effort towards population... increases the number of people before the means of subsistence are increased. The food therefore which before supported seven millions must now be divided among seven millions and a half or eight millions. The poor consequently must live much worse, and many of them be reduced to severe distress.”

Thomas Malthus, “An Essay on the Principle of Population”

A very common talking point is that the world’s population has a ceiling of some sort or another. It’s gone through many phases and formulations, but all three have a single common point: they’re all wrong.

The first reason why overpopulation as a complaint completely misses the mark is that global population growth has slowed down significantly in the past 60 years, when it peaked in the early 60s. This happened for a variety of reasons, in a phenomenon generally known as the demographic transition. Basically, countries tend to go through certain stages of population growth, which result in the population exploding at some point but then eventually slowing down.

The transition begins when countries are really poor. At this point, children are very likely to not survive their first five years, adults are prone to die violently or of disease, and people generally don’t make it past their 60s. People tend to have lots of children, because most of them work with their parents and they’re just trying to maximize the chances of them surviving into adulthood. Then, when medical technologies and sanitation improve, children stop dying en masse in their infancies, which means that suddenly the families that had six or so children with the aim of one or two suriving have all six living. This means that the population grows quite quickly at this point. People start having fewer and fewer children through the remainder of the transition, which also generally only results in lifetimes being extended at this point, until the population stops growing altogether. Migration can change this pattern, but it’s there for every single country - Europe went through it very early, Latin America is in the middle stages, Southeast Asia is getting there.

So overpopulation in the sense that the population simply never stops growing doesn’t seem to happen at all. There is a softer form of overpopulation argument - that the population will eventually stop growing as much, but that it will be so large that standards of living will plummet.

The most traditional case for controlling population in this sense it is the traditional Malthusian case. Thomas Malthus was a 19th century British cleric who wrote a book on economics, “An Essay on the Principle of Population”. The case he made was quite simple: the population grew exponentially, meaning it doubled every 30 years or so, whereas food production could only double much much slower. This meant that, at some point, there could be too many people for a given place, so they would start starving until famine or plagues or self-restrictions on fertility restored balance.

Malthusian thought was extremely influential in the 19th century, especially in Britain. Plenty of British colonies suffered from horrific famines, in large part because Britain pushed them into producing very specific crops, and then simply let people die when the need for food was too great - the Indians simply had too many children, and doing anything to feed them was crueller in the long run. The Irish Potato Famine is a less clear-cut case, but the British authorities remained bizarrely indifferent to them for clear-cut Malthusian reasons:

With no mechanism to slow population growth, population would continue to rise to the point where people actually started to starve. Malthusian economists thought that something like this had happened in Ireland, and blamed the Irish famine on overpopulation. Its ultimate cause, they believed, was the failure of the Irish peasantry to have fewer children despite their extreme poverty. As long as Ireland remained overpopulated, famine was inevitable. The only sustainable solution was a radical decline in both the Irish population and the Irish birth rate.

I have written about Malthus before, and I have complicated thoughts about why he was wrong. He wasn’t wrong, per se, because the demographic transition would happen - no country whatsoever had gone through it and there was no evidence it would. The real thing Malthus missed wasn’t just changes in technology that made agriculture (as well as every single other activity) more efficient, but also the power of incentives and institutions to shape human behavior. Had James Watt come up with the steam engine in the 11th century, or in a different version of England with different property rights, the Industrial Revolution would have never happened.

Anyways, Malthusianism gave way to explicitly eugenicist movements in the early 20th century - with a very obviously problematic part: the group of people there is too much of is, almost always, a minority. For example, the United States allowed sterilization of the “mentally defective” in 1927, and some states (like Virginia and California) continued carrying out sterilizations until as recently as 1979. Eugenics was all the rage in the 20s and 30s, and only really fell out of style because of its close association with the Nazis post-WW2 (even though they themselves had taken inspiration from other sources, particularly American eugenicists).

Fears of overpopulation, however, didn’t go away. In the 1960s, particularly the end of the decade, overpopulation became an issue again, partly due to an explosion in population in very poor countries, and partly due to actual environmental degradation. The former cause led to interest in aiming the world’s poor, either out of humanitarian concern or out of Cold War realpolitik. The environmental issue was tied to concerns about the sustainability of the global population, expressed by books such as “The Limits to Growth” or “The Population Bomb”.

American foundations drove this process by using aggressive family planning as a way to help poor nations develop by driving down the fertility of women in poor nations. A handful of Asian nations followed their recommendations of promoting birth control, voluntary sterilizations, and occasionally one or two child policies - like the one China has, with mixed results. The most infamous case was, once again, India: Indira Gandhi expanded a pre-existing voluntary sterilization program into a compulsory mass-sterilization drive as a part of her dictatorial experience.

Presently, overpopulation concerns have reared their ugly face once more, this time due to worries about climate change. Whilst this round mostly focuses on developed nations, it is both a weird sibling of the (very flawed) degrowth mindset, both of which handwave away the fact that the bulk of climate efforts will have to be made by developing nations, which account for the vast majority of CO2 emissions.

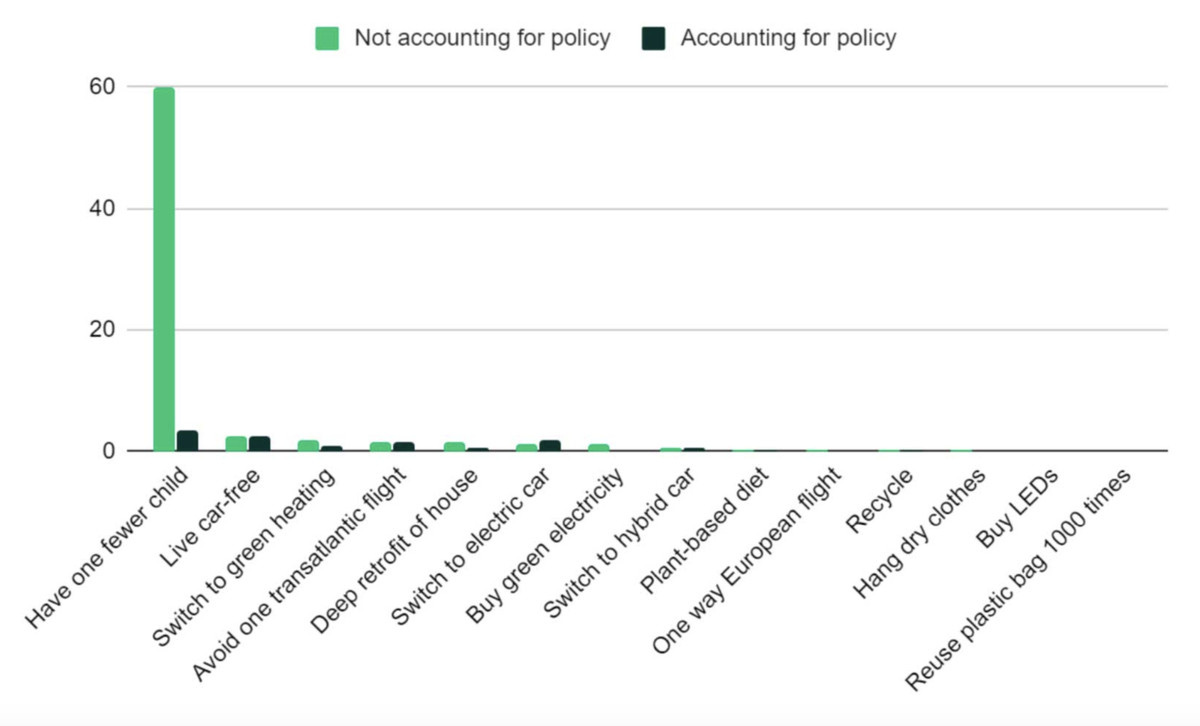

The most commonly cited statistic here is that having fewer children is the best way to prevent climate change. However, it is wrong, as it assumes that nobody does anything to slow down climate change, so all generations have the same carbon footprint as the present ones. If climate policy changes, then the impact of having one fewer child is basically the same as not owning a car - and if climate policy doesn’t change, then we’re already screwed and it’s unlikely having an extra child will make it much worse.

The real problem isn’t first worlders being wrong about how many children they should have (even though lower population growth appears to be bad for countries), but rather, that they decide that not only they won’t have any children with a first world lifestyle, but that they’re not going to take in any immigrants, since the population growth of most countries will naturally taper off in 30 years or so. Besides, climate change isn’t especially driven by population growth, but rather from increasing (carbon-intensive) consumption in regions that already had large populations.

Some have brought up the specter of “Avocado politics”: just like “watermelon politics" consist on laundering leftist laundry lists with environmental mumbo jumbo, avocado politics would represent enacting a highly conservative agenda under the guise of environmental action. Luckily, it doesn’t appear to be much of a thing yet, outside of Austria’s literal green-brown coalition and some ramblings from the Arizona GOP.

It should be noted that “ecofascism” isn’t a subversion of this line of thought; it’s something that is very much in tune with traditional Nazi ideas of a pure nature and Lebensraum. Martin Heidegger, the philosopher, was both an avowed environmentalist and a card carrying member of the Nazi party. Just like certain European politicians used the “socially regressive Muslim” stereotype to argue against openness to refugees, similarly inclined xenophobes will argue against immigration bringing up, in complete bad faith, the risks of ecological collapse.

All in all, overpopulation as a concept is just a messy jumble of falsehoods, non-empirical data, and racism. Overpopulation isn’t the reason poor, populous countries are poor, it’s not going to lead to widespread resource scarcity, and it’s not going to boil the planet. Anti-overpopulation climate types are basically those rich white homeowners who, sitting on properties worth millions of dollars, tell renters who commute for hours (due to the housing scarcity the homeowners caused) that the neighbourhoods is too crowded and they have enough homes. It’s just not an honest case to make, least of all because it’s false, and most of all because it’s incredibly offensive and unfair - rich countries got rich by pumping loads of carbon into the atmosphere and now they get to pull up the drawbridges and build a moat.

I think the point about "having children is only the most environmentally costly thing you can do in a policy environment that is unable to stop climate change anyway" is well taken, and I would add that the decision to have or not have kids impacts the climate on too long of a time frame to really matter (we need to make large changes within a decade, not over entire generations or lifetimes).

But something I don't think addressed here and what I read as the major driver of people's anti-natalism in the face of climate change is they just have a very dismal view of the future (56% of respondents in that survey said humanity was doomed because of climate change). If you think of the future as apocalyptic, it makes sense to not want to introduce new life into that future, and this is why I don't think it is a claim about overpopulation. Ecofascist narratives are generally concerned with preventing other people from having babies, what has gripped young people today is a separate issue caused by intense climate doomerism which centers their own potential children.

> Avocado politics

Not to be confused with neoliberalism 🥑