Was Malthus right?

Thomas Malthus thought that economic growth required a smaller population. He was wrong. But not for the reasons you think.

Thomas Malthus was an English cleric and early economist who wrote an incredibly influential book in the late 18th century, “An Essay on the Principle of Population”. In it, he argued that population grew geometrically (doubling every 20 years), but output could only grow linearly (doubling when all factors of production doubled) As a result, a larger population could only worsen standards of living. From the book itself:

We will suppose the means of subsistence in any country just equal to the easy support of its inhabitants. The constant effort towards population... increases the number of people before the means of subsistence are increased. The food therefore which before supported seven millions must now be divided among seven millions and a half or eight millions. The poor consequently must live much worse, and many of them be reduced to severe distress. The number of labourers also being above the proportion of the work in the market, the price of labour must tend toward a decrease, while the price of provisions would at the same time tend to rise. The labourer therefore must work harder to earn the same as he did before. During this season of distress, the discouragements to marriage, and the difficulty of rearing a family are so great that population is at a stand. In the mean time the cheapness of labour, the plenty of labourers, and the necessity of an increased industry amongst them, encourage cultivators to employ more labour upon their land, to turn up fresh soil, and to manure and improve more completely what is already in tillage, till ultimately the means of subsistence become in the same proportion to the population as at the period from which we set out. The situation of the labourer being then again tolerably comfortable, the restraints to population are in some degree loosened, and the same retrograde and progressive movements with respect to happiness are repeated.

Given that he considered land a factor, and the planet clearly has a limited supply of it (unless you’re Dutch), the conclusions are pretty grim: once the natural ceiling on population is breached, population growth will only decrease living standards. In consequence, once things get dire enough, famine will restore the economy back to equilibrium. There is some evidence of Malthus’s twisted idea of the population self-regulating through marriage and more/fewer birth rates. Malthusianism was actually a really influential view during Malthus’s time, and one with actual consequences. From O’Rourke (2015):

It is worth pausing for a moment to ask what would happen if population growth did not slow down as real wages fell. With no mechanism to slow population growth, population would continue to rise to the point where people actually started to starve. Malthusian economists thought that something like this had happened in Ireland, and blamed the Irish [potato] famine on overpopulation. Its ultimate cause, they believed, was the failure of the Irish peasantry to have fewer children despite their extreme poverty. As long as Ireland remained overpopulated, famine was inevitable. The only sustainable solution was a radical decline in both the Irish population and the Irish birth rate.

You can probably imagine what the British reaction to the famine was (hint: it wasn’t “do anything about it”) based on this logic. Racism against the Irish or Indians or whomever aside, here’s the thing: Malthus was actually right… but only prior to his time.

The Malthusian planet

Until the 19th century, give or take 100 years, standards of living barely increased. The best current estimates of GDP per capita show that it grew very very slowly until the Industrial Revolution: GDP per capita only tripled between 1270 and 1800, and going all the way back to the year 1 A.D., income per capita increased from roughly 1000 dollars (in France) to about 1300 in the year 1200. This is a disastrous performance, literally over a milennium to improve quality life just 30%, and then half of that time for a not very impressive (by modern standards) improvement. As John Maynard Keynes wrote in his essay “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren” (1931):

From the earliest times of which we have record—back, say, to two thousand

years before Christ—down to the beginning of the eighteenth century, there

was no very great change in the standard of life of the average man living in the

civilised centres of the earth. Ups and downs certainly. Visitations of plague,

famine, and war. Golden intervals. But no progressive, violent change. Some

periods perhaps 50 per cent better than others—at the utmost 100 per cent

better—in the four thousand years which ended (say) in A.D. 1700

Obviously, Malthus was wrong back then, but his backwards-looking assumptions weren’t as mistaken as we assume. So until the 19th century or so (roughly around the late 17th and mid 18th century is when the line is usually drawn), it’s reasonable to treat Malthus as mostly correct. People lived in a Malthusian economy: living standards were inversely related to the size of the population, because land is limited, and population growth is negatively related to standards of living. For example, take the Black Death: incomes increased by 50% in England in the five decades after it ended. This was because the economy was zero sum: since there wasn’t that much growth in output, fewer people meant a bigger slice of the pie.

Part of this stagnation was, clearly, that the population increased as output grew- meaning some increases in GDP per capita were obscured by very rapid population growth. And obviously the reason why everything got much better since 1800 was the Industrial Revolution, that both allowed for enormous increases in output per worker, and also coincided with a large expansion of the population (it doubled betwen 1200 and 1800, more or less, but has sextupled since).

Plus, Malthus’s argument was completely destroyed by the developments that followed: population, not just in Britain but the world, grew incredibly, about sevenfold in the last 200 years. Death rates went down significantly, birthrates soared, and nobody starved. In addition, agricultural land use has increased sevenfold since the 1600s - but global population has grown twice as fast, from some 550 odd million to 7 billion and change; and this is probably overstated due to the enormous weight that land for grazing cattle has, and the increase in meat consumption in the world’s poorest countries. In fact, yields on crops have grown faster than the population since the 1960s, when Malthusian ideas about overpopulation started being vogueish again; to the point that it takes 30% as much land to grow any given amount of crops than it did in 1961. Put another way, we could support three times the current global population, with 1961 standards of nutrition, without using any more land.

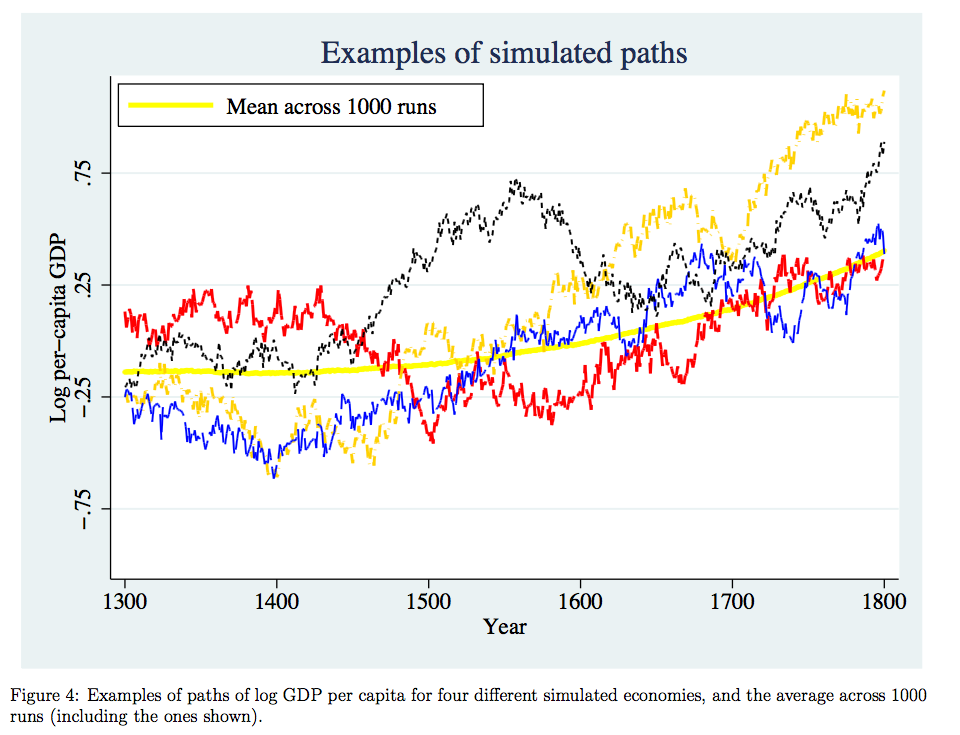

The first big problem with Malthus is that there was growth in income per capita in some European countries between 1270 and, at the “earliest” of the industrial revolution, 1660. This seems to have mostly been caused by either large drops in population that improved resources per capita, by technical improvements, and/or by large expansions of trade. This is somewhat reconcileable with the Malthusian model: using a realistic model of the age structure of the population and random shocks to land productivity, you can have an economy that seems to grow quickly but doesn’t actually.

This points to the transition from “Malthusian plenty” to “Malthusian poverty” (or Malthusian stagnation) taking a very long time, long enough that the required reversion of milder increases in standards of living wasn’t actually completed before the Industrial Revolution came around. Plus, the effects on age structure are significant: people just live enough for big jumps in population to persist over longer periods, since life expectancy after reaching your teens was 60 years old, and the reverse happened for big drops in population. Standards of living seemed to have been roughly constant until the late 16th century, consistent with a variety of improvements in technology and an expansion of trade, and the improvements in living conditions during the 1500s weren’t offset by the time the richest countries escaped from the Malthusian trap (roughly around the late 1600s).

Secondly, there actually were really big technological innovations: the High Middle Ages saw many improvements to farming techniques, the Renaissance rediscovered the medical insights of the Greeks and Romans, the printing press allowed for a distribution of knowledge across unprecedented scales, and there were plenty of discoveries regarding energy sources. These advancements in technology improved the amount of output per unit of resource, allowing more and more food without needing infinite land.

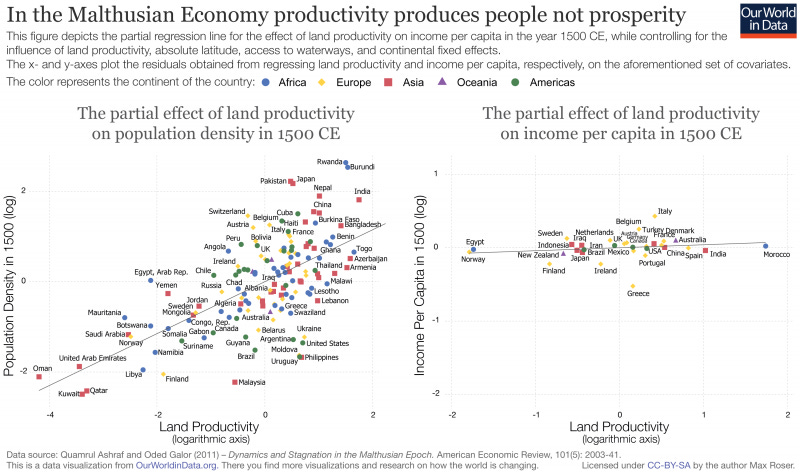

Well, for starters, as most increases in productivity of the time mostly benefitted the agrarian sector, they resulted in food yields improving. In the words of economic historian Gregory Clark “In the preindustrial world, sporadic technological advance produced people, not wealth.”. As seen in the graph above, increases in productivity lead to more people, not more output - probably because that’s the one use you have for more production when the only thing you make is food. Because big technological breakthroughs are so rare, and because population either grows very slowly or stops growing, then the economy doesn’t grow much and neither does the population.

What even is technology?

To continue our exploration of Malthusian ideas, we need a better grasp of how technology works. What growth theorists call “technology” t is, at its core, a set of ideas that boosts the effectiveness of labor.

These ideas have increasing returns, rather than the constant returns that other factors of production have. If you double the amount of capital and labor in an economy, you can make twice as many things, but if you double the amount of ideas, then you’ll have many times that increase. The reason why is simple: ideas are just the combinations of objects that lead to products people want. If you have 20 objects, the number of combinations of them lies somewhere along the lines of 10^18, or a one followed by 18 zeros. This is a really big number: if you spent a second trying every single one of those combinations since the creation of the universe, you would still have 80% of them left. But if you add one more object, then it goes to 10^19, or ten times more; you would actually have 98% of those ideas to be tried.

Ideas are also nonrivalrous: one person using an idea doesn’t diminish another person’s ability to use it. Meaning, once a thing is invented and people know of it and gain access to the idea, you don’t have to invent it again. Think of technology as a recipe to make food: once someone comes up with a recipe, you can just buy their book, instead of having to come up with it yourself. In fact, when Nobel Laureate (and husband of Janet Yellen) George Akerlof was introduced to this concept, his entertaining response was: “Yes, but how many of them are like chicken ice cream?”

You can incorporate ideas into economic growth models in a number of ways; the most common one, used by mainstream models of endogenous growth, relies on three main concepts: that knowledge spills over between firms, so that an innovation one company comes up with can be used by another company; and that firms can come up with ideas by doing business (learning by doing). The resulting changes means that, just by participating in the economy, ideas will interact with each other to create new companies and products - some of which will replace other companies and other products (creative destruction).

But the way endogenous growth works, it means that larger populations have larger economies, and that larger economies have more idea creation - a scale effect. It would seem to imply that larger populations produce more ideas, and thus have more growth. It would also seem like, all else being equal, countries with more population growth have more economic growth. The logic behind this is simple: even if the number of researchers and inventors doesn’t depend on the size of the population, and is instead some fixed proportion thereof, then more people will innovate.

Given the current state of the world, it doesn’t look like it’s true. But it’s actually compatible with the first phase of Malthusian insights: slow population growth led to small populations, which had very little knowledge output, which resulted in very low growth. Since economic growth enabled population growth, then Malthusian economies get trapped in a vicious cycle of ungrowth.

Farm to factory

How do nations leave the Malthusian trap? It does seem like they shouldn’t, because the “cycle of ungrowth” traps them, but they did, so it has to be possible for them to actually do so.

The question here, to be completely transparent, isn’t “why did the Industrial Revolution happen?”, but rather, why it was possible for it to happen at all. The key seems to be scale effects, i.e. that population growth and productivity are actually linked to each other. Let me explain.

For there to be an Industrial Revolution, there also has to be an industrial sector in the first place. Let’s just asusme that at least part of that technology existed beforehand. So there are, in fact, two sectors: an agrarian sector, and an industrial sector. The agrarian sector uses land, labor, and capital; the industrial, only labor and capital. The Malthusian economy is very land-intensive and “firms” are very small, like family farms; producing is always profitable, because salaries are very low. Since salaries are low, people can’t afford to have many children, and we can assume that their quality of life isn’t all that good. Even with productivity growth, because incomes are so low, then you can’t actually make a profit by converting your family farm into a factory, so to speak.

But if productivity grows just enough, then the population starts growing fast enough that costs to operate in the industrial sector get slightly ever so lower, meaning that a transition between the two starts happening. And productivity seems to grow faster, not constantly, when the population is larger, so the wealth swallowed up by feeding the farmers eventually leads to them being able to adopt the industrial technologies. This type of model suggests the industrial revolution was always inevitable, from the day the first monkey person walked even a semblance of upright in Africa.

A second potential explanation takes into account the interplay between education and technology; more educated workers have their skills boosted by technology, so output increases. Under an economy that hardly grows, there are no incentives to get educated, and because of the scale effects technology doesn’t improve much. Over time, the population grows just large enough that technology can start progressing on its own, which knocks it out of the Malthusian path and into a modern growth regime. This also boosts education, and educated workers have more “innovation output” (logically), so there is another virtuous cycle of technical change.

A big constraint on both of these is the fixed supply of land, that establishes diminishing returns to investment: not all land is the same quality, and worse and worse land has to be farmed by the end. So the innovations have to be big enough, and feed into each other enough, to kickstart population growth by being more relevant than the crappiness of the land supply they have to improve.

But… it does feel like there’s something missing in both of these; slightly smaller improvements in productivity, or slightly larger ones, or no Black Death or whatever could have either forwarded the Industrial Revolution a couple of centuries, or delayed it until living memory just as easily. And the technologies for industrial production have to actually be invented first, which could have taken an ungodly long time, and have to be available to everyone.

It seems that the missing piece of the puzzle is property rights. Very weak property rights would mean that inventors would barely get any compensation from their ideas, discouraging “investment in R+D” and reducing productivity, which ultimately would have delayed the Industrial Revolution. From Jones (1999):

The establishment of institutions that encourage the discovery and widespread use of new ideas can lead societies to outstrip Malthusian forces. However, the removal of these same institutions can allow the Malthusian forces to once again become

dominant. The technological frontier must be constantly pushed forward in order to avoid the specter of diminishing returns associated with fixed resources.

This would appear to explain why some periods of the past were particularly productive (for instance, the dawn of civilization, Ancient Greece, and the Enlightenment itself) and why others weren’t (the Middle Ages). Comically, it would appear that this ridiculous meme was actually correct, the Middle Ages just didn’t have the institutions required for the sort of innovations that (the golden years of) Ancient Greece and Rome were capable of.

In the words of Jones (99) again: “The cumulative effect of thousands of years of discoveries has been to raise the world population to levels at which the establishment of property rights could lead to large and rapid improvements in technology and standards of living.” And in fact, if property rights were different in the 20th century (when most of the spicy growth occurred), the economic boom of the 1940s to 1990s would have been delayed by just a tiny hair: until the 2300s.

Conclusion

It does seem that an unbelievably smug, self-satisfied, smarter than thou take on Malthus, a la “actually Malthus was correct about how the economy worked for 99.99% of human history worked” does have some backing to it and the person saying it is, in the most technically irritating way, correct.

However, Malthus missed very obvious things happening right to his face and in his own yard, like enclosures of grazing land or vast improvements to land productivity, that ultimately undid his own conclusions. Plus, he also missed another big factor: migrations, which were becoming more and more possible in his time - to the point where the bizarrely punitive solutions the British found to the Irish Potato Famine, following strict Malthusian recommendations, would have been completely unnesseary, since migrating to the New World (not to mention Great Britain) would have ammeliorated the solution on their own.

The Malthusian revival of the 60s and 70s, motivated by early environmentalism and the tragic famines that ocurred during that era, was also incorrect for the exact same reason. The ridiculous panic over the needs of more and more land to feed the world’s poor were, once again, thwarted by innovations in agricultural technology, to the point that what amounted to new fertilizers landed Norman Borlaug a Nobel Peace Prize. Plus, there was a racist tinge to many people’s Malthusianism, mostly because a lot of the Malthusians seemed to have very strong ideas about what kinds of people there were too many of (hint: not Europeans). This resulted in various morally repugnant conclusions, like promoting mass sterilization to reduce population growth.

Right now, overpopulation is both brought up as a blatantly racist dogwhistle or as an environmentally conscious concern (or sometimes, even both). The first is both despicable and factually inaccurate: the birth rates of countries goes down as time goes on, in a process known as the demographic transition. The second argument also misses the changes to labor productivity and the future of renewable energy, both of which will substantially reduce the “burden” that a growing population (at slower and slower rates, I might add) would result in.

Going out on a limb, it would seem that the somewhat Malthusian flavored degrowth movement suffers from the same blindness: they’re missing the awe-inspiring power of technology to get us out of tight spots. Of course, we can’t just sit back and let solar power’s implosion of costs do all the heavy lifting on its own, since it might take too long to actually do the trick. Rather, there is a large room for governments to subsidize as many carbon-saving technologies, especiallly in the third world.

Sources

Malthus

Max Roser (2013), "Economic Growth", OurWorldInData.

O’Rourke (2015), “Migration and the escape from Malthus”

Dietrich Vollrath (2017), “Who are you calling Malthusian?”

Fouquet & Broadberry (2015), “Seven Centuries of European Economic Growth and Decline”

Lagerlof (2018), “Understanding Per-Capita Income Growth in Pre-Industrial Europe”

Ashraf & Galor (2011), “Dynamics and Stagnation in the Malthusian Epoch”

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2013), "Crop Yields", OurWorldInData

Hannah Ritchie and Max Roser (2013), "Land Use", OurWorldInData

Ideas

Jones (2004), “Growth and Ideas”

The transition

Hansen & Prescott (1998), “Malthus to Solow”

Galor (2005), “Chapter 4: From Stagnation to Growth: Unified Growth Theory”

Kremer (1993), “Population Growth and Technological Change: One Million B.C. to 1990”

Jones (1999), “Was an Industrial Revolution Inevitable? Economic Growth Over the Very Long Run”