I’ve been recently rewatching “Narcos”, a Netflix show about the Colombian drug trade - particularly the stories involving the downfall of Pablo Escobar, head of the Medellin Cartel, and the manhunt for his main rivals, the Cali Cartel. But what exactly is a (drug) cartel, and how do they work?

The cartel economy

The term cartel actually comes from economics (specifically Industrial Organization, or IO, which studies competition and the like). The way to think about this is by understanding, roughly, the relationship between profits and competition. The more competitive a market is, the lower the profits - in perfect competition, which has infinitely many companies, nobody makes any profits. On the opposite end of the scale, if there’s only one company in play, the profits are highest because prices are high and quantities are low. For a given market, the more companies there are, the lower the profits; and if profits are high, more companies will want to join - unless there are barriers to entry, aka costs that make it unprofitable to enter past a certain level of competition.

If the level of competition is “in the middle” between monopoly (only one company) and perfect competition, they might engage in collusion - artificially keeping output low so prices go up and profits are high. You can represent this as the group of companies (the cartel) becoming a monopoly and splitting up their “turf” evenly between them. There are two main examples of non-drug related cartels: the De Beers Cartel for diamonds, and OPEC for oil. Both diamonds and oil are relatively abundant goods that are in high demand - so the price should, theoretically, be pretty low. However, locations that have either are not spread evenly, so it’s possible for most diamond producers or oil exporters to collude and keep output artificially low.

Cartels of any kind have a problem: it would be very beneficial for any single member to break away and slightly undercut the cartel, or produce more than their quota, which would increase their profits at everyone else’s expense. The decision to make is pretty simple: do the profits of being in the cartel indefinitely outweigh the gains from breaking it up and then collecting regular profits? To make this less attractive, cartels need to develop some sort of mechanism to punish members who break away - for normal ones is called a price war, where if the cartel is broken up, everyone will produce perfect competition quantities, or charge very low prices, to punish the breakaway. Drug cartels specifically also have actual wars, where they simply kill anyone who breaks whatever agreements they make in exceedingly brutal ways.

The reason why is simple: a cartel is stable only if the benefits of being in it are very large, and/or if the gains from breaking it up are very small. Factors that benefit collusion, and thus improve a cartel’s stability, are:

The industry being able to accomodate few firms, with factors such as high barriers to entry meaning that profits are naturally higher without collusion but also because new firms might not want to collude.

Members of the cartel being equally efficient or having similar capacity to produce - if one firm was more efficient, then it would have a much bigger market share, and everyone would have more incentives to break up unless the market is carved up in ways that both respect the biggest player’s share but also ensure that smaller members don’t try to undercut the rest.

Members of the cartel interact with each other often and/or have more information about each other’s business, since they would be able to detect collusion sooner and more easily.

The market is growing, since the benefits to staying in the cartel increase over time, versus remaining constant or even shrinking.

There are no possibilities for innovation, either through improved products or higher quality products, since this would mean some cartel members are more profitable than others and would be incentivized to collude - plus the others would need to undercut them as soon as possible to remain in the game.

So are cartels naturally stable? Not really. Barriers to entry aren’t very high, but there are increasing returns to scale - growing weed in your apartment is a viable business model, but so is setting up gigantic industrial-scale plantations in the jungle. This cuts both ways: the drug market is going to have a few behemoth firms, and plenty of tiny organizations. This also cuts into the second point: making a deal with Pablo Escobar is pointless when he’s going to benefit much more from a cartel than you. Interactions go either way, but drug cartels usually try to stay informed on who’s selling on whose turf precisely because of this. The market for drugs was growing rapidly in the early days of the trade, but now it’s pretty stable, and some major locations such as large US states or places such as Mexico and Colombia are toying with the idea of legalization - which makes collusion less likely, and could provide a reason for why Mexican drug cartels have gotten increasingly bellicose over the past 20 years. Innovations are the hardest one for cartels. There was a big switch from marihuana to cocaine in the 70s and 80s, and purer, stronger forms of both were created and refined over time - the reason is that the cost of trafficking the same amount of a stronger and a weaker substance are the same, but a stronger substance normally sells for more. In consequence, drug cartels will usually fight to create new, more potent drugs, resulting in the kind of asymmetries that turn cartels upside down.

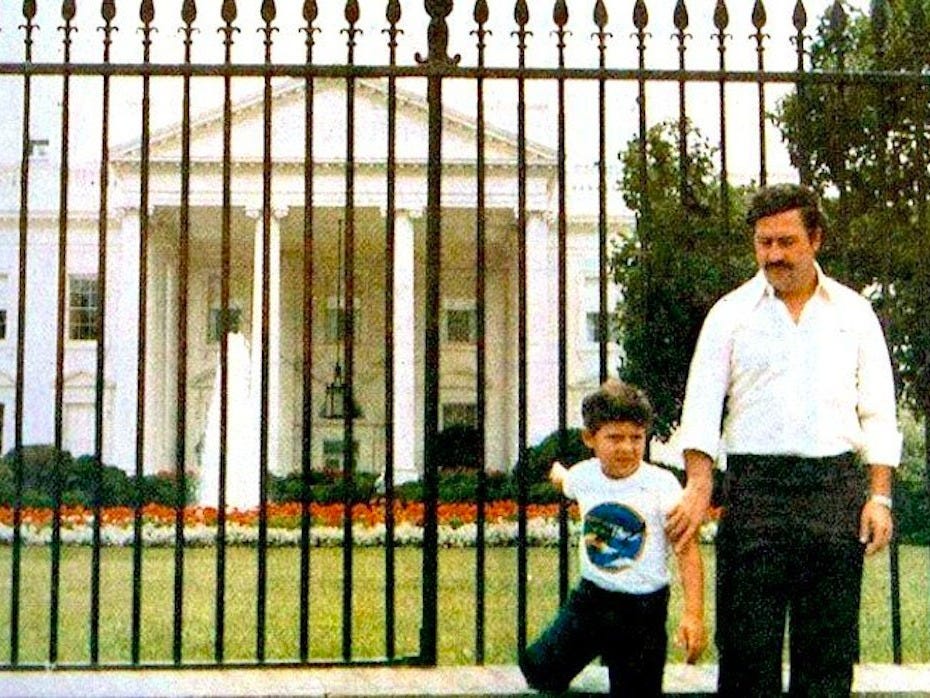

There is one unique factor in favor of drug cartels: agglomeration. Most cartels are located in single cities or regions: Medellín, Cali, Guadalajara, Sinaloa, Juárez, Tijuana, Michoacán, the South Side and North Side gangs in 1920s Chicago, or the Sicilian Cosa Nostra and Calabrian N’Dragheta. Drugs are mostly derived from plants, and plants have to grow in specific locations; plus, there are specific skills required to produce them. Finally, there is the necessary element of trust: since drug traffickers can’t sue each other for breach of contrast, their only recourse is violence, which means that people from the same community or family are usually first choices to form a cartel. Both the Medellin and Cali cartels were run by family members (Pablo Escobar and his cousin, or the Rodriguez Orejuela brothers), and it’s pretty common for American gangs to be formed within ethnic groups: the [nationality] mafia is a common trope for a reason, and the organizations in both Goodfellas and Casino (both based in true stories) don’t let characters who aren’t Italian become certified members. Another factor benefitting cartels is that the main markets for drugs are developed nations, but most drugs are made in developing ones - meaning that transportation costs are high, which favors larger organizations that can face those costs - and also favors specific locations to produce whatever is being traded. I’ve written a review of a book that goes more in depth on this ideas, so go read one and just imagine that instead of Silicon Valley and computers, it’s Mexico and cocaine.

An example of how agglomerations emerge, in a very Krugman- Fujita - Venables manner, was the Guadalajara cartel - the OG drug trafficking organization. Before cartels, the Mexican drug trade (which at the time produced weed, not cocaine) was run by plazas, local networks of dealers. The plazas were set up pretty simply: there was one “head dealer”, who got the position by killing everyone else who was up for the job, and who made sure turfs ran smoothly. If you wanted to join, you paid the head of the plaza a fee (called the piso) and were given territory and/or a quota, and you would be gruesomely executed if you broke this agreement. The cartel emerged by bunching up the plazas so they could exploit the better profits gained from producing and exporting at a larger scale - particularly because Guadalajara controlled a special type of marihuana that was more potent than the rest.

Because cartels are economically unstable, the only way to keep them together is by raising the costs of breaking them up through other incentives. Because price wars are unfeasible, cartels have to rely on violence to to enforce collusive agreements. The more violent the cartel, the likelier it is to get everyone in line. Another option is to purchase loyalty from politicians, judges, and law enforcement (or from paramilitary organizations) and have them do the dirty work, which is pretty much the same thing.

Silver or lead

But why do people become narcos in the first place?

Stephen Levitt, of Freakonomics fame (whom I hate, see more here) has a paper on crime rates and Lojack (a car alarm) adoption: when cars become harder to steal, people steal fewer cars, even for cars that don’t have Lojack. The reason I’m bringing this up is that it shows that crime is a rational phenomenon: people choose to be criminals and how to exercise their crime skills based on expected risk and profits1. Consequently, narcos would choose the narco path because it's a career - but why become a trafficker or mafioso, which isn't especially profitable for anyone except kingpins and godfathers, and not like an engineer?

If you look at people who were drafted into either Vietnam or the Argentinian military by a lottery2, you can see that draftees were much more likely to commit crimes (though there is some evidence suggesting part of this effect is caused by exposure to violent combat3) - and a likely explanation is the labor market. For example, people enlisted in any of the forces in Argentina's military were more likely to commit crimes, but people enlisted in the Navy were especially likelier - which isn't explained by any of the observable characteristics of the group, and because selection is random it can't be unobservables either. Thus, the likeliest reason for this is that the Navy requires draftees to serve for two years, instead of the usual one, suggesting a probable causal mechanism is military -> less labor experience -> lower earnings -> crime. Thus, conventional wisdom makes (rough) sense: more economic opportunities in mainstream employment and education reduces the likelihood of people becoming criminals. Unthinkable!

A lot of people recruited into the cartels no doubt think that their bosses are bad people and that the drug trade is bad for everyone. Which is something that both the government and the kingpins know. The decision to leave and join a cartel, both for specific gangs and for specific individuals, is understood through the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The story goes as follows: two criminals are arrested by the police, and kept in separate cells so they can’t communicate. The police has enough information to convict them for a minor crime, but if either cooperates they’ll have enough to prove a more serious one. So they offer the criminals a deal: if they keep quiet, they both go to jail for 1 year for the minor crime. But if one of them confesses, and the other one doesn’t, the rat walks free and the other one gets 5 years. There’s a catch: if both confess, then both go to jail for 3 years - because they cooperated, there’s some leniency. It’s evident that the goal for the two of them is to minimize jail time, so if they could cooperate, they’d choose to keep quiet and add up to 2 years. But for each prisoner, the situation is more difficult: if you commit to always keep quiet, then the best response for the other prisoner is to rat you out, and if the other prisoner commits to keep quiet then your best bet is ratting them out. So even in intensely loyal pairs, the best strategy to choose is to rat out the other criminal.

The government and the cartel both know this, and employ similar strategies: make their option more appealing and make the other option less beneficial. For the government, they usually promise traffickers who testify immunity for most of their crimes (aka lower the payoff from confessing), and often even offer visas to the US - resulting in a benefit, not just a smaller loss, from defecting. Meanwhile, traffickers use the threat of extreme violence, especially against family members who remain in the country, to make confessing less beneficial than jail - plus mob and cartel members who go to jail usually enjoy less severe sentences regarding their actual conditions (this scene in Goodfellas is not especially exaggerated), have their families provided for to some extent, and enjoy job security after serving their time.

Conclusion

Cartels are economic agents, and their members are economically rational actors making optimal decisions for their situation. But as the core tenet of modern economics goes, people respond to incentives: the government response to drug trafficking and related crime should be making the cartels as unprofitable as possible, and making joining them not especially beneficial, and not extreme violence that simply preserves and strengthens the more brutal and dangerous cartels. From Milton Friedman:

In an ordinary free market–let’s take potatoes, beef, anything you want–there are thousands of importers and exporters. Anybody can go into the business. But it’s very hard for a small person to go into the drug importing business because our interdiction efforts essentially make it enormously costly. So, the only people who can survive in that business are these large Medellin cartel kind of people who have enough money so they can have fleets of airplanes, so they can have sophisticated methods, and so on. In addition to which, by keeping goods out and by arresting, let’s say, local marijuana growers, the government keeps the price of these products high. What more could a monopolist want? He’s got a government who makes it very hard for all his competitors and who keeps the price of his products high. It’s absolutely heaven. Legalization is a way to stop–in our forum as citizens– a government from using our power to engage in the immoral behavior of killing people, taking lives away from people in the U.S., in Colombia and elsewhere, which we have no business doing.

This is opposite groups like terrorists and guerrillas, who tend to be middle class and highly ideological.

The reason why you can’t compare all draftees to all non-draftees is that there’s likely to be systematic differences that affect both outcomes and the likelihood to be drafted - for example, family wealth and connections, medical issues, education/employment, etc.

Not saying “all/most of it” because the effect of combat violence is weak for whites and very strong for non-whites, while the effect of being drafted is only significant for whites.

knew which goodfellas scene it was gonna be before i clicked it

now i wish i made spaghetti for lunch