Mini Post #9: Party Poopers

Did trains and the telegraph help actual trad wives to make the US ban alcohol?

I’ve been, for around two months, writing something different: a shorter, narrower post focusing on one specific study. Last week, I wrote about whether protesting increases support for the protesters’ cause. This is the tab with all the previous posts.

Onto the actual question of interest for the post: Did trains and the telegraph help actual trad wives to make the US ban alcohol?

We’ve all heard of the United States’s experience with Prohibition: between 1920 and the (Franklin) Roosevelt administration, it was illegal to buy or produce alcohol. In popular culture, it was linked to a rise in mob violence and organized crime. Regardless of its actual impact, it’s seldom discussed how Prohibition came to be implemented - particularly since a social movement sprung up to promote it.

In detail, the implementation of a US-wide ban on alcohol was driven by something called the Temperance Movement, which started in the 1840s or so and first urged people (mostly men) to drink in moderation, but later shifted towards banning drinking as its aim. One early social movement was the Temperance Crusade of 1873/74, a series of mass protests by women against the consumption of alcohol. It was both the first mass movement involving women in the US, and also the largest social movement involving political action of the nineteenth century, with over 150,000 supporters1.

This sets the stage for the paper in question: “Women, Rails and Telegraphs: An Empirical Study of Information Diffusion and Collective Action” (2018) by Camilo García-Jimeno, Angel Iglesias, and Pinar Yildirim. The question at hand is what was previously stated: was there a relationship between train and/or telegraph proliferation in the United States and women’s Temperance Crusade events in a given location?

Telegraphs are a no brainer: they allow for instant communication between distant locations. However, the telegraph network in the US was much smaller than the railway network, which made it a smaller (but no less effective) means of information transmission. Trains, meanwhile, are a bit weirder: why would railways help women organize anti-booze protests? Well, firstly, because people might have travelled and talked about it, obviously - “visitors, emissaries, missionaries, and delegates” are cited as important sources of diffusion of anti-saloon ideas in historical accounts. But secondly, because newspapers also travelled in (freight) trains, meaning that the people in one town may have learned about the rallies from the literal news.

There’s several important characteristics that make the Temperance Crusades a good fit for a study: first, the protests were very parochial and largely driven by local concerns, which meant that the causes and ramifications of each rally were largely unrelated to each other beyond “serving the same cause”. Additionally, since American women could not vote in all but two states (Wyoming and Utah), then collective action was pretty much their only channel, as a group, for political influence. Lastly, the movement did not have a centralized leadership or a planning committee, meaning that events simply happened as each location saw fit.

Now onto the data. The authors utilize a dataset that comprehensively tallies the number of women’s temperance rallies across the United States for the entire Temperance Crusade, including details of the characteristics of the events - meetings (as in, gatherings for discussion, usually at churches), petitions (self-explanatory), or marches (actual protests). One interesting fact is that meetings never took place after a petition or a march, but usually before, though with significant variation of what kind of events a town had. Additionally, they also utilize rail and telegraph data from the 1870 United States census, as well as research at Vanderbilt University and a Western Union directory. They also include data for each county on its location, gender composition, the strenght of various religious sects in the county, and the presence of saloons and various vendors. Lastly, to find data on newspaper coverage of the Crusade, they search a congressional database of historical newspapers to find words related to the events, as well as data on their location and timing.

The identification strategy the authors use is simple: with a comprehensive database of which towns had Temperance Crusade marches and when, and a comprehensive dataset of which had railways or telegraph connections, they obtain exogenous variation in connectivity to test for the influence of either network. They utilize strikes by railroad workers or train accidents as the instrumental variable.

An instrumental variable, simply put, is a variable that relates to the variable of interest but not the outcome variable - so, for example, if you want to test whether income predicts body weight, you might want to avoid endogeneity (for example, education or discrimination against heavier individuals) by using something like home values as an instrument for income - how expensive your house is might not have to do much with your weight directly. In this case, since having rail or telegraph access might be correlated with greater political mobilization, they use railway strikes as an instrument to find a negative effect - so, a strike might reduce the information flow into a county, and thus reduce political activity. Or not. One challenge, of course, is that the two types of events could be correlated: more active unions could also be a signal of greater political activity, and worse railways may result from worse government, which could have a less active civil society behind it. The authors don’t find any meaningful correlation between the presence of Temperance Crusade events and railway strikes or accidents - especially since the strikes and accidents often didn’t necessarily happen in any single pair of towns, but rather, in some other town that connects them.

The first step here is to put together a model: how can railways affect protesting behavior? Consider towns linked to a set of other towns by railway - this setis empty in unconnected towns, and has some given number in connected towns, which can change exogenously (i.e. unrelated to feelings on alcohol) depending on railworker strikes or on accidents. The same is true for telegraphs, although the intensity of the network gets weaker with distance. There’s also other connective routes, like roads or waterways, which have to be accounted for, and each network can boost each other: telegraph info of a rally reaches town A, which then writes about it on the newspaper and sends by train it to town B, which has a preacher travel also by train to town C - and someone who listens to his sermon takes a boat to town D and spreads the word.

This allows some conceptual clarity ahead of the actual estimation. Take an indicator for political activity: it will depend on, first the qualities of the town (demographics, religiosity, region, etc.), as well as effects by time (winter protests may be smaller). Secondly, it will depend on previous political action on towns to which it is connected through all three means (railway, telegraph, and traditional means), weighed by their distance and other intensity measures.

The effect is measured for each town between 50 and 150 days before/after an event occurred, and the results are quite straightforward: across different specifications (which mostly have to do with how lags are generated, to test for robustness), there is virtually no significant effect for traditional means of transportation, but there is a large and very significant one for railways, and an even larger, but less precise effect for the telegraph. Considering that on average 50 out of 15,000 towns had a Crusade event (that is, 0.003% of them), there being a Crusade event 5 to 10 days before raised the odds of the town in question having one by 660%. Disaggregating by type of event, the magnitude of the effect of telegraph and railroad coverage (both absolute and relative to each other) is very robust, though in some more precise specifications meetings have the largest effect - which is due to media coverage. This comes from a similar model, which instead of collective action, utilizes newspaper coverage of said action in a town and in neighboring ones subsequently, but with a smaller and smaller effect for more distant towns, both by conventional means and by railway. Lastly, the difference in efficacy of meetings is driven by more newspaper coverage.

The authors also utilize mathematical methods proposed by a different paper to test whether the spread of temperance activism was driven by inertia (that is some exogenous factor pushing it to the entire population at a fixed rate), contagion (that is, by “imitation” of a popular action), social influence (emulating people who participate) or by social learning (observation of behavior through interaction). The difference between the last two is that social influence spread depends on how many people do something, and social learning on how easy it is to learn about the action. Because of the shape of the spread, which is not linear, the lack of distinctive contagion patterns, and the lack of correlation between size and diffusion, it is likely that women’s temperance activism was driven by social learning.

One final question is whether the telegraph and the railway were substitutes or complements for each other. The authors estimate this by looking at all towns a given distance away from a town experiencing a temperance rally, and observing their rallies within a certain time period afterwards. The equation is quite convoluted, but simply measures the effect of rail with and without telegraph, the effect of telegraph with and without rail, and the difference between the two effects. With various time and geographic effects, and considering the demographics (gender ratio, immigrant share, Black population, newspaper diffusion, religious diversity, strenght of the most anti-alcohol religious sects, and population), the authors find that having joint telegraph and railway connections increase the likelihood of a Temperance march by 10% relative to having just one of the two. This effect gets stronger in a longer time window, but does not get weaker for larger geographical areas (though the other coefficients do).

This lets us conclude that the telegraph and the railway definitely helped the spread of women’s anti-drinking alcohol. Aditionally, this was aided by newspapers, and was driven by women’s information exchanges about the subject. Lastly, the two means of communication acted as complements for each other, and strengthened the activist’s diffusion of their cause.

In practical terms, there’s not a lot of evidence that women’s temperance activism led to short-term action (in fact, in some states the anti-temperance Democratic Party was strengthened in the 1874 election cycle, anecdotally), but it did lead to the creation of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, which was a fundamental player for both the Volstead Act (which banned alcohol) and female suffrage at large.

To finish the post, some links

The paper in question

Last week’s post, about whether protesting is effective

A 2006 paper by Andrews and Biggs about whether TV and radio coverage of protests helped the Civil Rights movement

A 2007 paper by Knight and Schiff about how social learning influenced support for John Kerry in the 2004 Democratic Party primary

A similar 2010 paper by Peter Koudjis about how weather in the English Channel delayed Dutch trading vessels and impacted stock prices

A 2020 paper by Moehling and Thomasson exploring how female activism, among other causes, promoted female suffrage

A 2020 paper by Cascio and Shenhav about women’s political participation and political affiliation after the 1920 legalization of suffrage

Other mass movements of the time, including temperance at large and the abolitionist movement, did have large enrollments but were not able to direct their members into coordinated action at the same rates.

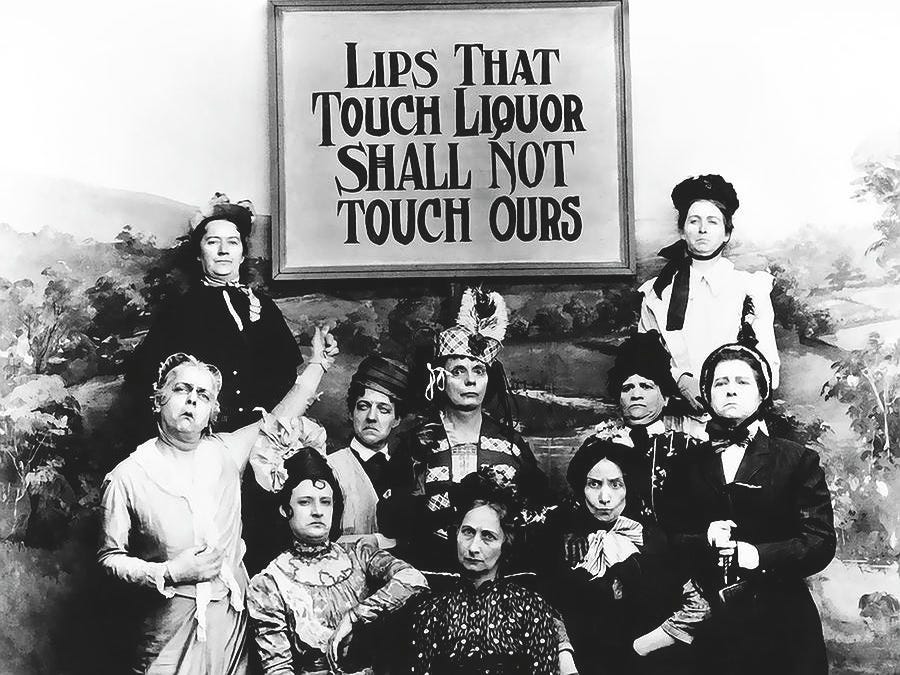

The ladies in the picture look like they know how to have a good time….