Mini Post #13: On Wednesdays, We Wear Pink

Are people with unique fashion senses responsible for more new technologies?

Lately, I’ve been writing a shorter, narrower post focusing on one specific paper once a week. Last week (technically two weeks ago but I’ve had a lot of work recently), I wrote about whether official poverty statistics accurately measure who is poor when they are poor. This is the tab with all the previous (and current) posts.

Onto the actual post: are people with more unique fashion senses responsible for more new technologies?

Culture, broadly defined, can be very important. People’s backgrounds and upbringing can affect their opinions, their preferences, and even their appearance. Choices in fashion can be one such aspect: some cultures demand certain sartorial choices, while others allow for freer decisionmaking. At certain times, skinny or baggy jeans are fashionable; or long and short hair preferred for either men and women - and this can reflect age, taste, countercultural leanings, or even ethnic/religious background. Thus, how people express their stylistic choices, thus, is both determined by and alters the overall culture they live in.

This is not new to social science: infamously, Francis Galton (Darwin’s cousin) tried to utilize people’s appearance to measure their moral worth. This is not really a productive endeavor, but looking at pictures of people can help understand their style writ large, and thus understand a aspects of the culture they live in. The paper in question, which is a working paper posted on Twitter, is “Image(s)” (2024) by Hans-Joachim Voth and David Yanagizawa-Drott, which utilizes pictures of high school students to figure out how certain metrics of style decisions changed over time.

First, obviously, let’s talk about senior portraits. In American high schools, it has been common for around 90 years for students in their final year of study to have their picture taken, which are then published in a “yearbook”.

To study the relationship between style and broader social patterns, the authors obtain around 350,000 yearbooks from classmates.com, a website that collates high school yearbook photos from 1930 to 2010, covering thousands of high schools in 44 out of 50 US states. To avoid issues with the representativity of the sample, the authors utilize a random selection of yearbooks from the top 3 high schools of the top 25 cities of each state, ending up with around 112,000 yearbooks in total (mostly before the letter N due to accessibility issues). Then, the authors utilize a series of algorithms to create a database of pictures of high school seniors from those scanned yearbooks, of which there are around 14.5 million. Then, the authors train a series of algorithms on human decision data to classify the images by gender and up to 25 style elements, such as hair length, facial hair, general clothing and accessory descriptors, and so on and so forth.

There are some general patterns to be noticed: seventeen year old men wore ties from the 30s until the 60s, and then fell precipitously from over 70% to just 10% by 2010. Long hair and facial hair in men were both very uncommon before and after the 70s. Women’s trend changes are fairly significant but have very little regularity - long and short hair go back and forth; jewelry goes back and forth. Certain characteristics usually go together: long hair and beards; ties and button-ups; jewelry and long hair. Pair those style elements together and you can form groups - men with suit, ties, collared chairts, short hair, clean shaven - and study its popularity. This “formal” male look made up around 85% of male looks; by the 60s, it was 75%, and declines to 10% by the 70s. Before the late 60s, four styles accounted for 90% of men; by the 70s, however, the most common style was “other”, which it remained ever since.

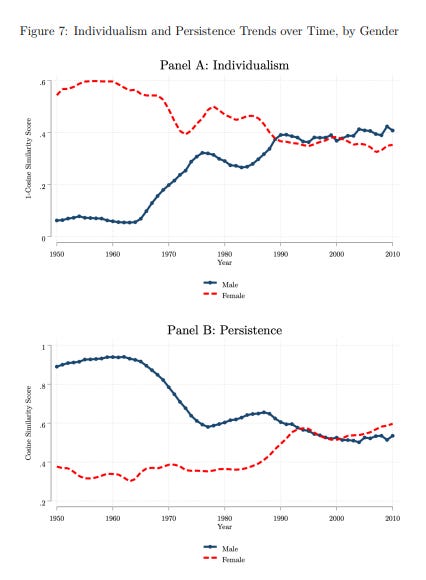

Given the general contours of “style” (hairstyle, grooming, accesories, clothing) the authors study three general categories: first, individualism, i.e. whether people have similar or different style from their general peers. Secondly, persistence - whether people wear similar styles than people who came a generation before before them. Lastly, novelty, which measures whether new styles are being invented (different than low persistence - older and newer styles ebb and flow, for example).

Individualism is measured by school, gender, region, and year by the average similarity between the styles of each person and of each other person in a school in a given year. A higher measure of individualism entails that fewer students look similar to each other. Persistence, meanwhile, is used by comparing a student to all other students in the same school, of the same gender, twenty years prior (or more/less in other specifications). Lastly, onto novelty. This measure is similar to the other two, but looks at how different a student’s look is from all previous and current graduates of their school and other schools - that is, the rarity of a specific combination.

Now, some initial results. The chart above shows the average values within and across specific high schools. For men, within-school indiividuality was extremely low from the 50s until the 60s and especially 70s, and at the same time they showed extremely high levels of persistence and low levels of novelty - that is, men’s styling decisions did not vary much from each other in general, and were more similar to previous men’s styles. In opposition, women showed much higher individuality and lower, but constant, persistence, and low levels of novelty - the high dispersion in looks made it rare than one was newer. After the 60s, however, female innovation in fashion declined progressively but substantially, and male innovation increased, so it was rarer to see women look extremely different to their mothers in the 90s, and more common to see men look different than their fathers. By 2010, both genders converged to more or less equal levels of innovation (that is, high individualism and novelty, low persistence), and there is no evidence of one gender “leading” the other, or of changes occuring simultaneously or at specific intervals. Fashion cycles are clearly observable: for example, the “70s style” was remarkably popular for parts of the 80s and 90s, and lasted for around a decade longer than the actual 1970s.

Overall, inventiveness in fashion (in the aggregate) increased over time for men, and decreased for women, so both genders converged by the 2000s and 2010s. The 50s and 60s were characterized by great uniformity (low individualism, high persistence, low novelty), and starting sometime around 1968, uniformity declined - though more in Northern US states than in Southern states. The between-school spread in fashion innovation increases substantially over time, so that schools are not only more different to themselves, but also to each other, with persistence and individuality being (inversely) correlated in each area. However, overall novelty remains low.

The authors also examine how specific style attributes affect each item - that is, whether wearing a tie is positively, negatively, or not correlated with individuality at a given time and a given school. Regressing novelty and persistence by style features for each decade at the individual levels, the authors find a series of interesting features: shirt with no collar was positively correlated with individualism in the 50s and 60s, but negatively in the 1990s. Bow ties remained a strong predictor of low individuality, while sweaters, long hair, glasses, and facial hair are always predictive of high individuality. For women, a bowl cut is always correlated with high novelty, except in the 1960s when this style was popular; curtain bangs went from reducing persistence to increasing it sometime over the 1980s. Comparing the association between unique names and unique styles, the authors test for whether there is a relationship between name rarity and individuality - and find none.

You may be asking yourself how is this economics? While economics journals publish many stupid things, there is a money-related point here. In his book A Culture of Growth, economic historian Joel Mokyr makes the point that irreverence is key for innovation - people who don’t respect established norms are more innovative technologically. Well, is this true? We could test this by looking at the association between fashion choices and the number of inventors in each area - using data from this 2019 paper by Bell and others. The authors use the study’s data on inventors per commuting zone, by year, and by age of inventor per patent, and match those zones to each of their high schools. Then, they define a group of “top innovation” as a new style adopted by less than 1% of previous high school students up to that point; if the share of such styles is greater than zero, it is classified as “high innovation”, if it is not, it is low innovation.

Let’s look at one example: Steve Jobs. Jobs, the founder of Apple, graduated from Cupertino Homestead High in 1972. In his yearbook picture, he’s wearing a tuxedo, a bow tie, long hair, and doesn’t have facial hair or glasses. When he took his picture, it was a rare style; shortly after, it became fairly common. He also received 960 patents, and applied for 254 more that were not granted. Does this extend to other people who are both fashion and technological innovators? Yes. There is a clear and positive statistical significance between innovativeness in fashion and in technology, but only for novelty (when adjusting for population). As population increases, the premium of novelty on patenting becomes weaker, perhaps because unique personal styles are more common. Across time, there are substantial statistically significant differences in rates of innovation - for men, after age 20 they peak at a 50% higher rate of patenting, and for women they peak at a premium of 100%. The overall level of patent activity drops over the decades for men and rises, then drops for women (reflecting, in the aggregate, lower innovativeness in the economy in the last few decades, and for women particularly, first increased access to STEM jobs, and later, the impact of macro-level trends), but the premium of unique style grows alongside this difference.

So, what have we learned? Well, that style has changed across time, where it has gotten more personally unique for men, and less unique for women, but at levels that are broadly similar by gender in the present. Additionally, we have also learned that there does not seem to be a clear correlate between the uniqueness of a person’s name and the uniqueness of their style, although this could be because the name is chosen (generally) by a person’s parents, and “unique fashion sense” may not be a heritable trait. Lastly, it’s clear that having a more unique personal style is positively associated with innovation later in life; not causally (making men wear earrings will not cause them to become inventors), but rather, by reflecting an overall permissive, irreverent, and individualistic culture.

To finish the post, some links

The paper in question (and a link to a Twitter thread by one of the authors)

A blog post by Alice Evans examining how depictions of women in Egyptian visual media shows the country’s changing attitudes towards gender.

A 2011 paper by Yuriy Gorodnichenko and Gerard Roland on the importance of individuality for economic growth.

A 2020 paper by Bazzi and others on how exposure to frontier culture shapes a person’s individualism, as measured by naming choices.

A 2019 paper by Bell and others about who becomes an inventor in each area

A 2024 paper by Michalopoulos and Rauh about what kind of movies people with different values prefer (which I’ve written up before).