Jumping the Rope or Pulling on a String?

Do bigger recessions happen because of too much growth, or does fast growth come after bigger recessions?

Is the magnitude of an expansion related systematically to the magnitude of the succeeding contraction? Does a boom tend on the average to be followed by a large contraction? A mild expansion, by a mild contraction? (…) Let us now ask the same question, except that we start with a contraction and ask how its amplitude is related to that of the succeeding expansion.

Milton Friedman (1964), “Reports on Selected [NBER] Programs”

What was the most important economic idea to come out of the post COVID macroeconomic landscape? While most of the discussion has been primarily focused on stimulus size, inflation, what is a recession, or optimal policy to balance unemployment and price stability, the truth is that the answer might be even simpler: do deeper recessions end faster, or do deeper recessions lead to bigger expansions?

A traditional view

There is a “natural rate of unemployment” at any time determined by real factors. This natural rate will tend to be attained when expectations are on the average realized. The same real situation is consistent with any absolute level of prices or of price change, provided allowance is made for the effect of price change on the real cost of holding money balances. In this respect, money is neutral. On the other hand, unanticipated changes in aggregate nominal demand and in inflation will cause systematic errors of perception (…) that will initially lead unemployment to deviate in the opposite direction from its natural rate. In this respect, money is not neutral. However, such deviations are transitory, though it may take a long chronological time before they are reversed and finally eliminated as anticipations adjust.

Milton Friedman (1976), "Nobel Lecture: Inflation and Unemployment”

The traditional view of the business cycle is very simple. There is a level of GDP that occurs when all factors are utilized to their maximum availability - what a Keynesian would describe as “full employment” or a neoclassical [sic] would say is “equilibrium”. Either way, actual output can be below potential (a recession) or above potential (inflation), and policy has to be expansionary below and contractionary above.

The maximum level of potential output is also paired with a maximum level of sustainable unemployment, and an interest rate that balances out the capital and credit markets. All three are not correlated with demand, but rather determined by supply - particularly, by the stock of the factors of production (labor, capital, and human capital, aka education) and by technology.

Whereas supply can be capped at a certain level, demand can either be higher or lower, so the business cycle is primarily accounted for by aggregate demand - when there is too little spending in the economy, too few people have jobs, too few factories are open, and too few loans are given out. On the contrary, when there’s too much spending, the amount of actual stuff being supplied is constant, so this simply pushes up prices since there isn’t actually any more capacity left in the economy.

Now, this doesn’t mean that recessions and inflation are equally bad - if it’s harder to cut prices (or wages) than to raise them, then companies will have too few customers for the same costs, and will have to lay off workers. This would happen too in an inflationary environment, where companies face the same customers but higher costs, but since raising prices is easier, inflation will have lower costs. And it also doesn’t mean that the economy has to be the same before and after the recession or inflation - the real composition of the economy (preferences, technology, composition of production, etc) might mean that there is a higher or lower equilibrium rate of unemployment “permanently”.

This view, which I will label the “natural rate view”, “booms” are positive deviations from the maximum potential, and therefore have to be followed by a “bust” - the key empirical prediction here is that the size of the recession is proportional to the size of the preceding expansion. If the economy grows “too much”, then it should be too high above potential, and eventually it’ll have to be pushed back down to stop or prevent out-of-control inflation.

A monetarist alternative

Consider an elastic string stretched taut between two points on the underside of a rigid horizontal board and glued lightly to the board. Let the string be plucked at a number of points chosen more or less at random with a force that varies at random, and then held down at the lowest point reached. The result will be to produce a succession of apparent cycles in the string whose amplitudes depend on the force used in plucking the string. (…) In this analogy, the irregular underside of the rigid board corresponds to the upper limit to output set by the available resources and methods of organizing them. Output is viewed as bumping along the ceiling of maximum feasible output except that every now and then it is plucked down by a cyclical contraction. Given institutional rigidities in prices, the contraction takes in considerable measure the form of a decline in output

Friedman (1993), “The “Plucking Model” of Business Fluctuations, Revisited”

In 1964, Milton Friedman proposed an alternative view: the “plucking model”. In 1964, Friedman asked the same question in this post’s description: is there a systematic correlation between the sizes of recessions and contractions? And if there isn’t - what kind of correlation is there between the two phases of the business cycle? His alternative was that the size of a recession is not proportional to the previous expansion, but rather, to the speed of the subsequent period of growth.

The key here is that potential output measures aggregate supply, and the story there isn’t very different to the natural rate story: factors of production and how you mix them up. But because actual supply matches demand, then it’s not reasonable to say that there can be more demand than supply - you’d have to be buying things there’s literally nothing of. So, as a result, potential supply can’t be exceeded - there’s a ceiling on the level of economic activity, determined by the economy’s growth rate.

This makes perfect sense for recessions, since there’s not really anything different, but it does tell a different story for inflation - why isn’t there “too much demand”? Well, the answer comes from prices and wages not adjusting perfectly and instantly. When prices go up, some don’t as much (for some reason), and therefore real income goes down - not as much, since prices and wages can adjust upwards more than downwards, but still down. This, in turn, imposes a real ceiling on spending during inflationary spikes - and therefore real demand should follow the “plucking” pattern.

The big implication here is that rapid expansions of real demand aren’t systematically followed by large imbalances between spending and output, resulting in recessions proportional to the expansion. Rather, this means that (for some reason), larger recessions should end faster once proper support is provided. This doesn’t mean faster growth (which is guaranteed because of base effects), but rather, faster completion of the recovery. The exact causal mechanism wasn’t disclosed by Friedman, and newer work has proposed relying on nominal rigidities to explain the assymetry.

The facts

What does the evidence say? This is a really important question, and Friedman (being, at least in this regard, an empiricist) staggered the publication of his paper by 29 years between proposing the plucking model in 1964 and searching through the data to test it in 1993. The tests implemented then were pretty rough, so I’m not going to go in great detail over his original verification.

However, there have been more recent attempts to verify Friedman’s theory with more modern data. The key issue, as with most macroeconomics, is that most countries have only a couple of decades of reliable national accounts, and most of them have only had a handful of recessions - which tend to be correlated between countries, adding a huge endogenous component to the regressions.

Historical international evidence

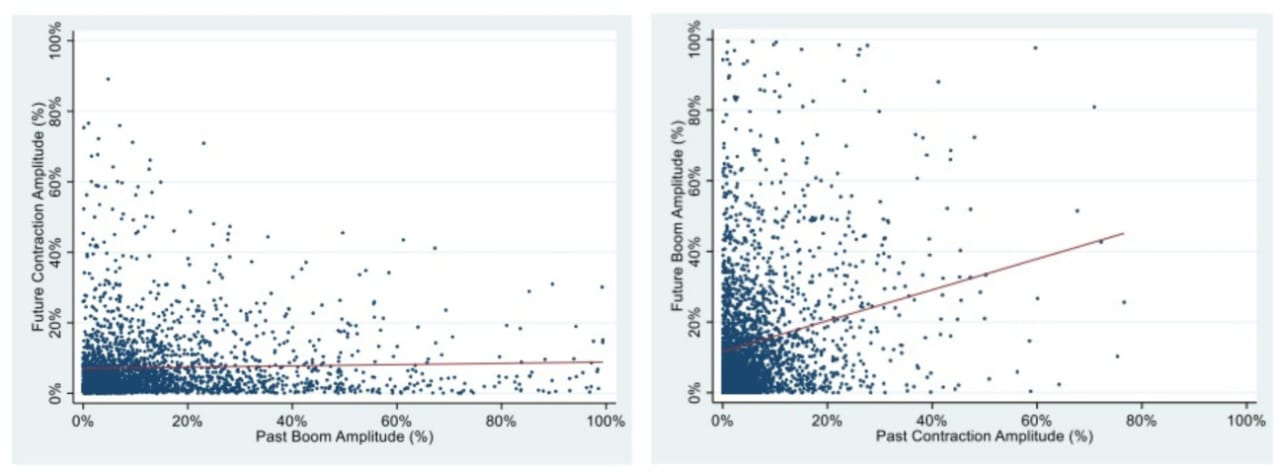

A first attempt can be made using data from the Maddison Project, which estimates national acccounts over several centuries for some 169 countries. Hartley (2021) utilizes datasets for those countries, with heterogenous time coverage (some go as far back as the 13th and 14th centuries, other just the 20th) - and finds a striking relationship. On the left is the proposed “natural rate” relationship; on the right, the “plucking model” relationship:

As you can see, there isn’t really any significant evidence pointing to the natural rate hypothesis - the slope is not statistically different from zero. Meanwhile, there is a strong, positive relationship as predicted by the plucking model - pointing to it being a better representation of reality. However, the Maddison Project’s methodology has been criticized, so the degree to which it can offer illuminating insights is probably not ironclad.

US unemployment evidence

Secondly, an estimate from a paper by Dupraz, Nakamura, & Steinsson (2021) on the plucking property of the unemployment rate specifically. Since unemployment tends to move alongside GDP (meaning, goes up during expansions but goes down during recessions), it should show the plucking property as well. However, unemployment is also less responsive to expansions than to recessions - which is hard to explain under most common theories. Their results also point in the same direction:

On the left, the plucking model relationship; on the right, the natural rate relationship. Once again, a strong, healthy, positive slope on the left, no slope (statistically) on the right. Given thaat US unemployment data is considered reliable and fairly high quality, and that unemployment rates have varied substantially over the past 75+ years, therefore it’s not subject to the same considerations as the previous attempt.

COVID and the plucking model

COVID-19 was a very tough time, but for macroeconomists there is a single silver lining: the variation in COVID cases and economic activity can generally be considered more exogenous to economic policy than in previous recessions. Since recessions are often preceded by overly tight monetary policy, therefore it’s hard to evaluate such claims - but since COVID resulted in differing degrees of economic contraction and economic recovery based on government responses, epidemiological factors, and social preferences, therefore there is a recent dataset of high quality that can be used to test out the hypothesis. Probst (2021) does this, for a Mercatus Center symposium on Milton Friedman. As usual, the results were pretty one sided:

There isn’t a comparable estimate for the natural rate hypothesis, but there is a regression for the 2008-2009 Great Recession (which is also the subject of an excellent Bruegel post). Overall, both of the latest global recessions seem to point to 1) the depth of a recession having predictive power over its speed, and 2) the size of an expansion having no predictive power over the subsequent contraction.

Conclusions

Is the plucking model true? Friedman wouldn’t agree with this characterization, but it certainly seems better than the alternative. The weak spot of the model is, of course, the lack of a precise causal mechanism for the plucking property itself. Dupraz, Nakamura, & Steinsson (2021) seems to rely on nominal rigidities of some sort or another, which points to the plucking model and monetary neutrality running generally in tandem: whatever accounts for neutrality accounts for the plucking model, and vice versa, and if one fails, so does the other. This also allows for the Quantity Theory of Money to subsist, in a modified version that accounts for such facts at least: if the plucking model is an accurate characterization, then que QTM seems an adequate enough approximation of reality as well.

The biggest implication here is for policy. The recipes for expanding economic potential and for responding to recessions seem to be equal under both views, however, optimal policy during expansions differs significantly. Under the natural rate view, policymakers should moderate expansions, since it is possible that real demand will begin exceeding potential significantly and therefore force a much bigger, more painful contraction to bring down inflation down the line. However, since such deviations aren’t possible under the plucking model, policy should focus on controlling inflation if and only if nominal demand exceeds nominal potential output, which would signal “too much money chasing too few goods” - although not on moderating real expansions themselves absent pressures on price stability.

Sources

Previous posts on the Quantity Theory of Money, monetary neutrality, and Nominal GDP Targeting.

Introduction to the plucking model

Friedman (1964), “Reports on Selected Bureau Programs” - pages 14 to 22

Friedman (1993), “The “Plucking Model” of Business Fluctuations, Revisited”

Bruegel, “The “Plucking Model” of recessions and recoveries”, 2015

Evidence

Hartley (2021), “Friedman’s Plucking Model: New International Evidence From Maddison Project Data”

Dupraz, Nakamura, & Steinsson (2021), “A Plucking Model of Business Cycles”

Probst (2022), “What Would Milton Friedman Say about Business Cycles? The Plucking Model View”

Monetary Policy is what "controls" the "pluck".

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2011/10/23/plucking/