Bullseye

What is Nominal GDP Targeting?

A number of modern luminaries of the academic and policy worlds have spoken and/or written in favour of NGDPLT: Nobel laureate Paul Krugman (2011), former chair of the Council of Economic Advisers Christina Romer (2011), former Federal Reserve Bank chair Janet Yellen (Bernanke and Yellen 2018), St. Louis Fed president James Bullard (Bullard and DiCecio 2019), Dallas Fed senior vice president Evan Koenig (2010), Chicago Fed president Charles Evans (2019), former Bank of Canada (and Bank of England) Governor Mark Carney (2012), Bennett McCallum (H.J. Heinz Professor of Economics, Carnegie Mellon University and member of the Shadow Open Market Committee, 2011), Michael Woodford (John Bates Clark Professor of Political Economy, Columbia University, 2012), Jeffrey Frankel (James W. Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth at Harvard’s Kennedy School, 2018), former Bank of England deputy governor Charles Bean (1983), Peter Ireland (Murray and Monti Professor of Economics, Boston College and member of the Shadow Open Market Committee, 2020), and many others.

Ambler & Rowe (2021), “Choosing the Right Target: Nominal GDP Level Targeting”

As casual readers of my blog, or followers of my Twitter, might know, I’m a big fan of monetary economics and monetary policy. A big item of debate like ten years ago, which has recently come back, is the idea of Nominal Gross Domestic Product (or NGDP) Targeting. What is it, what are its advantages, and does it have any demerits?

Quantity over Quality

I’d say that the core of NGDP Targeting is the Quantity Theory of Money (obligatory post link). The core of the Quantity Theory is the equation of exchange: MV = Py, the supply of money (M) times the speed at which it changes hands (V) equals the price level (P) times real output (y). The core implication here, as reflected by stylized facts, is, basically, that in the short term money can affect real output (i.e. changes in M can cause changes in y), but over the long term they are only reflected as changes in prices - inflation or deflation. Of course, if the economy grows 20% in a decade, the only way to keep prices stable is to print 20% more money (over the decade).

The insight here is pretty simple: inflation happens when there’s too much money chasing too few goods, so people bid up demand and companies can’t respond (because supply is generally thought to be pretty inelastic in the short term), which means they just raise prices. On the contrary, recessions happen when there’s too little money going around, simply because people are afraid of spending it (because, say, they might lose their job), which means that many companies don’t make enough to keep afloat and have to cut costs - often by firing workers. Both of these imply there’s a “neutral” level of GDP: in this “goldilocks” economy, there’s neither too much or too little spending, so there’s no excess inflation and there’s also no excess unemployment. But how do you get there?

A pretty weird implication here is that inflation-adjusted spending, i.e. real GDP, can never be above the neutral level. This happens because of two reasons. The first is that real GDP measures, roughly, how much “stuff” there is in the economy, and if inflation is caused by companies not being able to produce more stuff, then it can’t actually go up with excess demand. The second is through what’s known as sticky prices (or, for the more seriousness inclined, nominal price rigidity). Basically, the idea here is that not all prices adjust at the same time, so some companies (and people, since wages are sticky too) end up losing out when inflation goes up, so that has real output costs. Imagine a bakery that can’t raise prices, for whatever reason, but faces higher costs and higher wage requests - they’re going to struggle to make as much bread, let alone the same price. Why prices (and wages) are sticky is a whole thing, and it doesn’t really matter all that much because the empirical implications across theories end up being basically the same.1 This conception of the (real) business cycle, that it’s actually going below or at a maximum level is known as the plucking model, and was one of Milton Friedman’s best ideas (as well as the most underrated).2

From MVPY to NGDP

Let’s say that the goal of monetary policy is, roughly, economic stability - preventing inflation and recessions. Going back (once more) to Milton Friedman, monetary policy can control nominal but not real variables - i.e., it can control dollar amounts, but not volumes. Because the Fed can control the amount of money (with some limitations), it can steer the amount of spending, and thus order around things like inflation and nominal wage growth. But real variables, like unemployment, real output, or real wages, it can’t - the Fed prints money, not things. There is a demand-side component to them, but ultimately supply dominates: if you want more stuff, you need to get better at building it (or for the government to spend on roads, either way works).

The Fed controlling nominal spending through its control of the money growth poses the question of which part of the equation to focus on, MV or Py. Let’s start with MV: money is pretty straightforward, but velocity is a crapshoot, which poses a question: if you want economic stability, choosing M as your main policy variable doesn’t cut it. You can keep money growth steady and still get inflation or a recession simply because people hold too little or too much money for too little or too long time, and you have no clue why - velocity is a real variable and monetary policy doesn’t really determine real variables, not in equilibrium. Plus, banks actually create most money anyways, and they basically choose whatever amount they want, so trying to nail down how much money they’ll produce at any given point is a fool’s errand.

So, if you follow all of the abovementioned logic, that means the Central Bank should focus on stabilizing Py and not on stabilizing MV. Since P*y = Y, aka nominal GDP, you’ve got your targeting. But what does having “a nominal GDP target” (or nominal income or nominal spending or nominal output target) mean?

Who targets the targeters?

Most central banks currently have what’s known as an inflation target - a fixed inflation rate they have to eventually guarantee they’ll reach. This means that all monetary policy decisions are aimed at hitting that target, with some caveats. Nominal GDP Targeting works the same way - you pick how much spending there should be in the economy best on your best estimate of the neutral level, and then you do “whatever it takes” to get there. Importantly, you have to stabilize the level of NGDP, not the growth rate (though stabilizing the level normally means a stable growth rate), since if you have a shortfall or an excess you’ll never make up for it. Comitting to never being too far off the path you’ve promised means people will tend to act as if NGDP will always be on track, which makes actually keeping it on track always and everywhere significantly easier.

The advantage picking NGDP over inflation as a target is pretty simple: information. To accurately decide how to respond to inflation, you need to know the source: too much money or too little stuff. Depending on the situation, untangling them can go from difficult to impossible - and picking a response is even harder. If it’s too much money, you just tighten policy. If it’s too little stuff, the best response is to do nothing - to quote Allan Meltzer :“Money cannot replace oil, and monetary policy cannot offset the loss of real income resulting from the oil shock.” A negative supply shock reduces potential and actual output in ways that more money can’t solve. An inflation target requires profound knowledge of the situation in many, maybe even all markets - something Friedrich Hayek cautioned is impossible. And the Fed’s track record at seeing through supply shocks is shockingly bad - there’s an argument to be made that a large part of the contractions associated by oil shocks is actually a product of overly contractionary monetary policy due to an inability to “look through” them.

However, if instead of inflation you pick nominal spending as the outcome to watch, things become significantly simpler. In a demand shock, prices rise but quantities do not - so the same reaction. But in a supply shock, quantities and prices move in opposite directions, meaning that nominal output remains constant. This is pretty simple: if the economy isn’t any bigger (in fact, it’s smaller) and gas gets more expensive, people are either gonna spend less on gas and more on other things, or more on gas or less on other things, or less on both and have a recession, but not more on both - money isn’t infinite. The knowledge about the actual economy required to stabilize the economy at all times is far lower than targeting inflation.

The way to measure whether monetary policy is good or bad is also pretty straightforward: is NGDP too far away from the neutral level. If NGDP is at the neutral levels, the economy is eating the right porridge and sleeping in the right bed. However, if it’s not, then that means that money is going around too quickly or slowly, which means there’s either too much or too little money relative to the amount of stuff. And because of the aforementioned “knowledge treshhold” being much lower, then it’s far easier to respond - because shocks the Fed can’t respond to don’t show up in the data the Fed is looking at. The composition of the NGDP level changes, of course, with more prices and less output, but no reaction is needed as long as the level itself doesn’t - getting rid of a major problem.

Another big technical benefit concerns the existence of liquidity traps. A liquidity trap, in modern terms, occur when a central bank’s promises to raise inflation are not believable to individuals, since they expect the bank to crack down on prices as soon as inflation picks up. If the central bank has a lowermost interest rate it can hit (called the effective lower bound), then it’s possible for the economy to get stuck in a “bad” equilibrium of low rates, low (nominal) growth, and low inflation - just like Japan. Because inflation targets cannot credibly commit to leaving the bad equilibrium, you just get stuck there - because, even in flexible regimes, you can’t credibly commit to make up for past outtakes. But because NGDPT commits to making sure the level stays constant, then it doesn’t fall into the trap because there’s no credibility to flex: expectations are anchored to nominal income, not to inflation, and it’s clear that you would have to “take away the punchbowl” after returning to the trend, not before.

Things fall apart

Is there something we’re not seeing? Yeah, there is. Policymakers and academics alike have issued several significant complaints about NGDP that I’d like to bring up, in an effort to be balanced on such a major departure from current best practices.

A first issue, and one the Federal Reserve has actually debated, is that experts believe nominal output targets would be too difficult to communicate to laypeople. Most people don’t really understand what GDP is, and don’t understand what “nominal” means, so it would be possible that benefits to credibility aren’t realized because nobody understands what the hell the Fed is going to do. This is a reasonable concern, especially after the FAIT debacle, and one that can’t really be addressed in any satisfactory way - just develop better vibes. Of course, people don’t understand anything about the Fed already, so it might not make a difference anyways.

The second issue is about how to pick a starting point. A big advantage of NGDPT is that it relies on observable variables (nominal GDP) instead of unobservables, like the NAIRU or the natural interest rates. If there’s a stable trend of real economic growth, and any desired level of inflation whatsoever, it should be pretty easy to just draw a straight line and know what to do, rather than getting lost playing among the stars. The problem, besides the obvious “what is the desired level of inflation”, is that it’s not really clear from where to draw the line. Pick a recession, you’ll get too little income; pick an inflation, you’ll get too much. You could try to gauge when NGDP was neutral, but that requires relying on unobservables again. A secondary issue is that real growth trends seem highly variable: productivity growth was high in the 50s and 60s, low in the 70s and 80s, high in the 90s and early oughts, low again until COVID.

A third issue, one near and dear to my heart, is that the data on GDP is quarterly and, by the time it comes out, pretty outdated. Plus, if you try to gauge the NGDP Gap, you also have to rely on estimates of potential output that are constantly getting revised. To give you an example of how severe this problem can get: there’s something called the Taylor Rule, which, TL;DR, proposes raising interest rates a lot when inflation goes up - the current Taylor Rule3 recommendations are rates in the 5% to 8% range (vs 2-3% for normies). So it’s super hawkish. In the 60s and 70s, monetary policy was extraordinarily dovish, leading to very high inflation by 1971 and stagflation through the 70s. However, if you put in the estimates for the real interest rate and, more importantly, the real output gap the Federal Reserve was using, you’d get that actually monetary policy was wholly in line with what Taylor would have told them to do4. Delays in data, and revisions to important datapoints, have been extremely important to the performance of monetary policy.

You can get around this one in two ways. The first is that, in fact, GDP forecasts have been getting pretty good lately, much better than in the 90s, so it’s possible to develop estimates that are at least unbiased (meaning that, on average, they don’t go too high or too low). A related solution is what’s called “targeting the forecast”: instead of targeting NGDP itself, you target market expectations of it5, so that policy only moves when markets predict that monetary policy is in the wrong. This absolves you of having to guess neutral NGDP, at least in real time, but doesn’t eliminate the revisions problem (after all, markets have to see actual results too), and it’s possible nobody actually trades, or nobody does anything in a clearly deteriorating situation because the market is waiting for the Fed and the Fed for the market. This isn’t very realistic, because the Fed could also just decide to act, but it does weaken the regime.

Conclusion

Instead of summarizing the main points, I’ll talk about something else entirely: what would NGDPT argue we do about inflation today? Well, as we’ve mentioned above, the key issue is that supply shocks are not reflected in nominal spending - if the price of cars, oil, food go up because there’s less to go around, people adjust their behavior in an economy that’s the same size (or smaller). As a result, all deviations from the neutral level correspond to demand - and so the goal of monetary policy isn’t to go after everything that happens to prices and output, just to what it can actually affect.

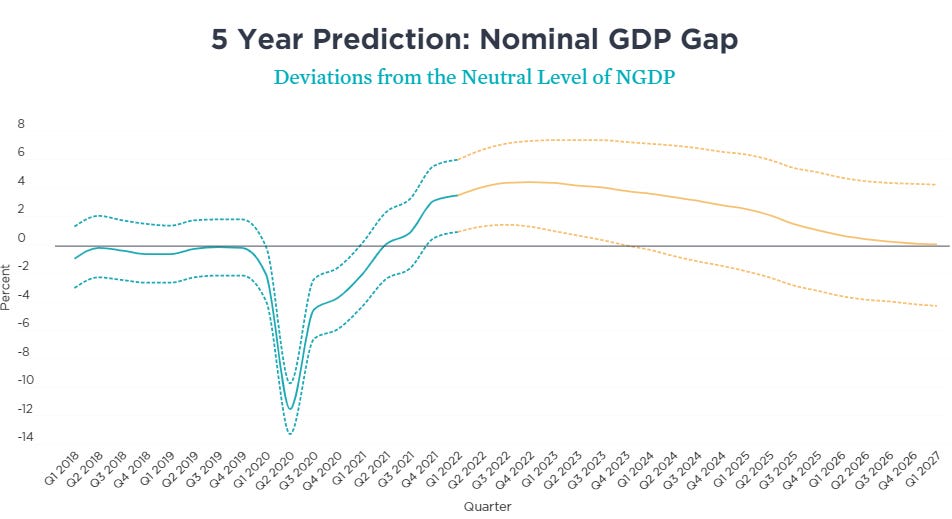

The question, then, is what’s causing inflation. There is, of course, a demand component - the deviation from the NGDP trend (approximately the neutral level) is as high today (3.4%) as it was in the mid 1960s. But since inflation back in the 60s was in the 4-5% range, this implies about half the excess inflation is amenable to monetary policy, and half is not. Due to this Larry Summers-esque reasoning, it’s clear that monetary policy should only target the part of inflation that is caused by demand, which would need the stance of monetary policy to be significantly less aggressive than is currently discussed. The chances of a soft landing (i.e. constant unemployment and stable inflation without a recession) are slim, of course, but far less slim if the indicator to look at is nominal income and not inflation. A hard landing, meanwhile, is just a plain old recession where inflation goes down and unemployment goes up. In NGDPT terms, the gap would gradually go down to 0 without turning negative in a soft landing, and would go sharply down into the negatives in a hard landing.

It’s also worth noting that, if nominal expenditures were the indicator to watch, and forecasts or nowcasts of it were your gauge (for instance, at the Dallas Fed), then the Federal Reserve would have spotted the upcoming inflation in Q3-21 (i.e. September) rather than earlier this year - when the NGDP gap was a quarter its current size. Monetary policy mistakes have consequences, and having started tightening policy a full two quarters early would have definitely increased the chance of a soft landing and reduced the chance of a recession. In fact, during a discussion back in June of last year, it was argued that Nominal GDP Targeting would have made the Fed tighten policy in anticipation of inflation - which was then seen as a terrible mistake, but in hindsight was the correct position. Hindsight is 20/20 (or 20/21, in this case) but it’s fairly clear that making better recommendations on policy is always a plus.

Sources

My post on the Quantity Theory of Money

The Quantity Theory

Lucas (1995), “Nobel Lecture: Monetary Neutrality”

From micro to macro

Koenig (1995), “Optimal monetary policy in an economy with sticky nominal wages”

Probst (2022), “What Would Milton Friedman Say about Business Cycles? The Plucking Model View”

Basil Halperin, “It was a mistake to switch to sticky price models from sticky wage models”, 2021

The nuts and bolts of NGDPT

David Beckworth (2019), “Facts, Fears, and Functionality of NGDP Level Targeting”

David Beckworth (2017), “The Knowledge Problem in Monetary Policy”

David Beckworth (2020), “The Stance of Monetary Policy: The NGDP Gap”

Ambler & Rowe (2021), “Choosing the Right Target: Nominal GDP Level Targeting”

Scott Sumner (2012), “The Case for Nominal GDP Targeting”

Disadvantages of NGDPT

Carola Conces Binder, “NGDP Targeting and the Public”, Cato Institute, 2020

George Selgin, “Lars Svensson on NGDP Targeting”, Cato, 2019

Orphanides (2002), “Monetary Policy Rules and the Great Inflation”

Orphanides & Van Norden (1999), “The Reliability of Output Gap Estimates in Real Time”

Sumner (2013), “A Market-Driven Nominal GDP Targeting Regime”

For those of you who are curious: the three main explanations are that people can’t tell which prices are increasing for “real” reasons (preferences, productivity, etc) and which ones for inflation reasons - called the Lucas Islands model; that raising prices has a cost (Rotemberg pricing model); or that companies just have to wait around to be able to raise prices (Calvo pricing model). Calvo pricing is the one ultimately chosen because it’s less weird than the Islands model and less weird with the facts than Rotemberg pricing.

There’s actually a case that NGDPT is just a very weird Taylor Rule, but let’s move past that.

Worth pointing out this is mostly symptomatic of how bad macroeconomics was at the time, not really on the whole idea of GDP forecasts. The Dallas Fed got it right!

Will read again, the what's the "neutral level part" for well timed policy changes seems like a really interesting problem conceptually.