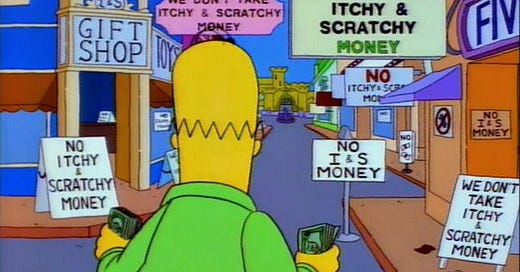

Itchy and Scratchy Money

What the hell is a stablecoin and why did they lose all their value in two days?

Last week, the biggest stablecoin (a specific type of cryptocurrency), TerraUSD, lost its parity with the US dollar and crashed to 0.3 dollars, so a 70% reduction in value. But what is a stablecoin, how did the parity work, and is there a way for normal people to understand all of this?

Like regular currency, but fun

What is cryptocurrency?

All jokes aside, cryptocurrency is basically a type of currency that, instead of being created by a country’s (or a continent’s) central bank, is created by descentralized transactions on the blockchain. The blockchain is sort of a ledger that keeps a record of all transactions with complete accuracy and transparency. Cryptocurrency is created differently from regular currency: instead of being made by a central bank with a printing press, cryptos are “mined” in a descentralized fashion by solving of complex mathematical operations with high-powered computers. This ensures, to put it briefly, that the supply of any cryptocurrency is kept finite.

And what is a stablecoin? Well, it’s a type of cryptocurrency, obviously, that has a fixed parity with the US dollar, normally one to one. This is so their value is, not very excitingly, stable. The way this parity is kept is by holding either US dollars or, more commonly, other cryptocurrency, such that whenever supply and demand push it above or below the parity, a centralized operator can sell the reserves (either dollars or other cryptos) to stabilize their value, or in some cases, an algorithm mints more or fewer coins to prevent changes in value. Terra, the stablecoin that crash, was backed by another ad-hoc cryptocurrency called Luna (the Earth and the Moon, clever), which a Singaporean group called the Luna Foundation Group could stabilize to stabilize Terra. This is way less complicated than it sounds and we’ll come back to it in a bit.

Is cryptocurrency an actual currency or is it just a weird scam for overly online men? Cryptocurrency is a currency because it has the one function of currency, performing transactions. They’re sometimes illegal, like hiring hitmen or buying organs, but nobody said that currency has to be used for good things. Economics textbooks say currency has three uses: means of exchange (being useful to buy things), store of value (being useful to “save”), and unit of account (measuring value). Now, the first one is obviously performing transactions; but why do people save? To spend in the future, aka perform future transactions. And why do people need to measure value? To perform some transaction or another.1 So currency only really has one use, performing transactions. It doesn’t really matter where the solved sudokus come from or what they are, only that you can trade them for heroin.

In the General Theory, Keynes claims people demand money for three reasons: performing transactions (see above), hedging from various scenarios, and speculation. The first one is by far the weakest of the three, but this isn’t too uncommon - a good example is the demand for US dollars in unstable countries (link to a blog post broadly about that). People rarely use them for transactions, and instead as a savings device (see the above linked blog post) and frequently for speculation2. Bitcoin and other cryptos are usually the source of speculation, naturally, but they were were usually cheered for as inflation hedges, so all of this tracks.

RubleCoin, redux

This brief foray into monetary economics 101 wasn’t just a flex, but to explain what approach I’m going to take. You can understand was happen as either a “stock market” event, and explain it through finance, or as a monetary event, and use monetary theory. I’m not a finance person, so I’m going for the latter.3 Now, superfans might realize that I’m about to touch on an issue I’ve already talked about, the collapse of the Russian ruble roughly two months ago. I’m gonna take a slightly different approach here, because the balance of payments is less important and the monetary aspect is more important.

The key analogy here is simple: the stablecoin crash was a balance of payments crisis. The balance of payments aspect is not fully relevant, because Terra is not a national currency, so I’ll really boil it down4. The balance of payments is the flow of foreign money going into or out of a country. It has three parts: the current account, the capital account, and the financial account. Each part is defined as:

The current account has the goods trade deficit, the services trade deficit, net interest payments, stuff like rent or wages paid to/from foreigners, and remittances. So, transactions with counterparts, and remittances

The capital account has a lot of weird wacky stuff that doesn’t happen very often, like external debt forgiveness, intangible assets transfers (i.e. intellectual property), or things like football player sales/purchases.

The financial account5 has investment into the country, both in the forms of assets (bond or stock purchases), or foreign direct investment.

The balance of payments is reflected in the country’s international reserves - aka the amount of foreign currency the central bank has. For example, Argentina had a (roughly) fifteen billion dollar trade surplus last year, which means its gross reserves (the Scrooge McDuck money pile) went up by fifteen billion. But the central bank used its reserves for a variety of things, so net reserves (the amount the country actually has) barely went up or even went down, depending on the estimates.

The main determinants of the balance of payments are interest rates and the exchange rate. Interest rates primarily factor into the financial account, and they’re ruled by something called interest rate parity: a country’s interest rate must equal the international rates plus the expected devaluation of its currency plus the risk premium, which is the risk that the country will do something really stupid6. The central bank generally controls interest rates, and besides from domestic economic considerations, it also considers whether it will (de)stabilize the currency.

The exchange rate can either be nominal or real. The nominal exchange rate is the amount of one currency that another one can buy - for example, one dollar can buy 200 pesos, and one peso can buy 0.005 dollars. The real exchange rate is how much of what one unit of a currency can buy in one country can be bought in the other country with its currency. So, for example, if the United States was 200 times more expensive for every good, then the nominal exchange rate would be 200, but the real exchange rate would be 1, because each currency can buy as much as the other. This means that a nominal devaluation (or nominal appreciation) is how much the exchange rate goes up (or down), whereas a real devaluation is the exchange rate going up more than inflation. The Argentinian peso was devalued roughly 15% last year, but the inflation rate was 51.9%, so there was real appreciation of about 30%.7

Something really interesting about cryptocurrency is that the exchange rate fully reflects the price level of the US dollar - what is known as price purchasing parity. But because the bitcoin exchange is frictionless, and there are no tariffs or shipping fees, then the market exchange rate for bitcoin and the PPP rate for bitcoin must always be the same. For example, if buying a human liver costs one bitcoin, and a bitcoin is worth 29,000 dollars, this is because a liver is worth 29,000 dollars. If the value of bitcoin doubled, then liver prices would halve.

The exchange rate can, in the extremes (like perfect competition and monopoly) either be determined by the free market or by the central bank. In the first case, known as a floating exchange rate (or “a float”), if there are more buyers than sellers, the exchange rate goes up, and viceversa. Conversely, the central bank setting the exchange rate is known as a fixed or pegged exchange rate (or “a peg”), and whenever there is excess demand, the central bank sells its reserves; it buys reserves when there is excess supply. Very few countries have either completely fixed pegs or completely floating rates, and operate somewhere in between: for example, a lot of countries devalue their currency at the same rate as inflation (to prevent domestic products getting more expensive for foreigners), or determine “zones of intervention” where the exchange rate acts as a float between two limits and as a peg above or below them, to prevent instability.

But because of interest rate parity, a choice in the exchange rate regime also implies a choice between two other things: either limiting the ways the financial account operates (capital controls) or not having a choice on what the interest rate is. This is known as Mundell’s Trilemma (no relation) and it is fundamental to monetary policy. For example, Argentina has a (quasi) fixed exchange rate, but doesn’t want to have the rate determined by interest rate parity (something like 75%), so instead it heavily restrics capital flows. However, Hong Kong is a heavily financial economy, so it can’t do that, and instead it chooses to not have independent monetary policy. Because Hong Kong and the US are very different countries8, this means monetary policy is frequently very bad for Hong Kong’s specific needs.

We all float down here

The reasons why some countries would have pegs and others floats are very complicated, but most commonly countries that don’t have a lot of reserves tend to have floats, and countries that want to stabilize the currency choose pegs. Currency pegs were really common in 70s, 80s, and 90s Latin America because inflation was really high, so the central banks tried to stabilize the currency by pegging the exchange rate to the US dollar. This didn’t really work in the 80s because of the Volcker Shock, and also because of extreme real exchange rate appreciation.

Currency pegs can be self-defeating when monetary policy remains expansionary, because there is a financial account deficit (without controls) or because inflation continues going up, resulting in a current account deficit. If the central bank has enough reserves to back the peg, nothing happens. But just like the problem with socialism is that you run out of other people’s money, the problem with pegs is that you run out of other country’s money. When this happens, it’s called a balance of payments crisis, and the way it occurs is simple: the sharks smell blood because central bank balance sheets are public information, so they start buying up currency at the pegged rate to deplete the reserves in one go. The central bank runs out, and has to break the peg, resulting in a devaluation. For example, this happened to Britain in 1992, when George Soros bet against the British pound; the Bank of England didn’t have the money, and Britain had to withdraw from the European Rate Mechanism. In countries with capital controls, people just buy dollars to have and to hold, and this ends up draining reserves eventually. Older models, like Krugman (1979), have this be a fairly painless, benign process, but posterior ones can have messy abrupt devaluations. If you factor in that devaluations can have real effects on the economy9, then a balance of payments crisis is very bad, and countries that attempt pegs they can’t maintain several times end up harming the economy more than helping.

But you could say “what if the Central Bank didn’t have an expansionary monetary policy” or “what if the Central Bank had enough reserves to back the peg”. Well, a balance of payments crisis can still be triggered. One way this could happen is by a self-fulfilling prophecy. If “speculators” expect that there is a chance that the central bank might adopt expansionary policies that are incompatible with a stable trajectory for the peg (for example, a recession might happen, or the bank might accomodate rather than offset a larger fiscal deficit), then they might start getting antsy about that possibility triggering a balance of payments crisis, and the only rational response to expecting a balance of payments crisis is to trigger it immediately, to be on the winners’ side (the people who bought low and sold high) and not the losers’ (the ones who didn’t).

The other way this happens is a sudden stop. They’re frequently associated with currency floats, but can actually happen under pegs too. Many countries choose to have very high interest rates so because they can prop up their reserves: having rates at or above interest rate parity causes foreign investment to increase. The problem is that investors can start worrying that the central bank wants to lower rates, or that the real exchange rate is unsustainably low, so they might want to pull out of the country. This “concern” about the sustainability of macroeconomic policies can often be reflected as an increase in the risk premium, which often can lead to even higher rates that only heighten concerns about unsustainability. If a big chunk of investors pulls out of the country, this could trigger a regular balance of payments crisis because them leaving the country drains reserves, so a big enough stock of foreign investment (and therefore big enough concerns about the fallout) can send everyone running to the bank to get dollars while they’re still cheap. Countries with floats have the same problem, because a sudden stop simply sharply devalues the currency suddenly.

Houston, we have a problem

So what exactly happened with the Terra - Luna pairing, a few other stablecoins, and the general crypto market? The first thing to understand is that people who invest in crypto might invest in several currencies at once, so one crashing might make them pull out of all of them. In the “real world”, this is known as contagion, and normally happens either when the countries that suffer a financial crisis are very similar, or simply due to misreading regular signals. For example, a bank may offload its assets in Mexico because of bank-specific factors, but other banks may thing there’s something bad with Mexico, so they offload too, and suddenly everyone starts getting worried about a place like Colombia or Ecuador or Panama, so they offload too, and then it spreads around Latin America. This means that if one crypto goes down, many others follow, which obviously has ramifications for crypto-backed stablecoins.

But the mechanism of the Terra coin, and most stablecoins, is actually rather interesting because instead of being an old fashioned peg, it’s a much rarer type of fixed exchange rate arrangement known as a currency board. Currency boards are really rare because they don’t just imply a peg, they also center monetary policy around preserving it. A very good example is Argentina’s 1991-2002 currency board, which also pegged the peso at a one to one parity against the dollar, and which also had major restrictions on how monetary policy could be conducted. Something worth pointing out is that the currency you’re pegging your own to is known as the anchor, and the anchor doesn’t necessarily have to be a currency - it can also be gold, such as in the 1886-1890 Argentine currency board. But having a currency board backed by a currency different from the anchor isn’t very common, and it’s probably the kind of thing that only really happened under the gold standard.

Currency boards are not very frequently used because of two reasons. The first is that countries tend to like having independent monetary policy, and a board makes having rates lower than the international level impossible, giving policy a deflationary bias by definition. The second one is that they haven’t historically been very successful, with the two examples from Argentina ending in massive financial crises. The 1886-1890 example was just very inconsistent, since the government both had a currency board and allowed banks to issue as much gold-backed currency as they liked, creating significant moral hazard. The 90s example is really really complicated, but as a summary, the deflationary bias plus a multilateral real exchange rate that started falling further and further as other countries broke their own pegs. The growing BoP deficit due to an overvalued currency became worse due to sovereign and private debt payments, meaning that interest rates needed to be incredibly high to preserve the parity. And abandoning the parity would have thrust the country into a Great Depression-style event, as debts (highly dollarized) would have soared, the entire financial system would have collapsed, and the government would have been unable to pay off the national debt.

The whole stablecoin debacle was far less complicated, since there isn’t a real economy, a credit system, or trade deficits involved: people, much like George Soros in 1992, started betting that they didn’t have enough assets to back its peg. Knowing that contagion is possible, any crypto-backed stablecoins would have been in hot water if these bets caused a self-fulfilling prophecy. The events in question around Terra specifically were very much like a regular balance of payments crisis: investors started accumulating short positions on the parity. The Singaporean foundation responsible for it promised to sell up to a billion dollars in various reserve cryptocurrencies to prop it up. This restored confidence, and “capital controls” (limits on withdrawals on several exchanges) helped the stablecoin recover. However, news emerged of the LFG looking for additional borrowers, which sent it plummetting further down, until some big crypto exchanges completely suspended operations. Similarly, a few of the reserve cryptos were also stablecoins, and they were also suffering from their own big balance-of-payments issues due to insufficient reserves, many of which were supposed to be in US dollars. The loss of value of the whole crypto market dragged the value of crypto-backed stablecoin’s reserves down, sending many of them down a death spiral.

Conclusion

I mean, the biggest one is that fixed exchange rates arent’ very smart, and backing them with a different currency than the one you’re pegged to is even worse, especially if there are high chances of contagion between your currency and the reserve currencies. The stablecoin situation is more technically complex due to the nuances of the crypto market, but more simple because there really isn’t a “national economy” to consider, and especially no balance of payments. So it ends up being all reserves and credibility, with the added complexity that your reserves could start crashing in value at the exact same time as your own currency faces a potential speculative run.

Sources

My blog posts on Argentina’s demand for US dollars, the Russian economy, and the 1998-2002 Argentine economic collapse (in Spanish and English)

Josh Hendrickson, “When A Dollar Isn't a Dollar”, Economic Forces

Mike Orcutt and MK Manoylov, “Terra, Luna and UST: How we got here”, The Block

The basics

My blog post on Argentina’s demand for US dollars

BBVA, “Stablecoins: what are they and what do they do?”, 2019

George Selgin, “A Three‐Pronged Blunder, or, What Money is, and What it Isn’t”, Cato

Louise Davidson, “Keynes’s Finance Motive”

International monetary economics

My blog post on the Russian economy

The Economist, “Two out of three ain’t bad”, August 27th 2016 issue

Frenkel & Rapetti (2010), “A concise history of exchange rate regimes in Latin America”

Balance of payments issues

Krugman (1979), “A Model of Balance-of-Payments Crises”

Obstfeld (1996), “Rational and Self-Fulfilling Balance-of-Payments Crises”

Dornbusch, Goldfajn, & Valdes (1995), “Currency Crises and Collapses”

Some conclusions

My blog post on the 1998-2002 Argentine economic collapse (in Spanish and English)

Calvo (1999), “Contagion in Emerging Markets: When Wall Street is a carrier”

Dornbusch, Park & Claessens (2000), “Contagion: Understanding How It Spreads”

Calvo (2003), “Sudden Stops, the Real Exchange Rate and Fiscal Sustainability: Argentina's Lessons”

For example, monetary estimates of what a human life is worth aren’t done as an intellectual exercise in economists being sickos, but for court settlements and fines, which are transactions (very sad ones, but still).

In Argentina, it’s frequent for people to buy US dollars at the (lower) official exchange rate at the start of the month and sell them at the (higher) black market rate at the end of the month. So, for example, you can buy 200 dollars at 150 pesos each and sell them for 200 pesos - netting you about 10,000 pesos. This is called “making puree”, and it nets a profit at least equal to the monthly inflation rate plus the black market premium.

You can read a very easy to grasp approximation of the finance side on the Economic Forces substack post about this same topic. Even I, a finance illiterate, got it.

More detail in the Russian ruble blog post.

Some papers and textbooks, especially older ones, don’t differentiate between capital and financial account because the capital account proper barely matters, and instead call the combination the capital account, which is needlessly confusing.

For example, Uruguay has a country risk of 161 basis points, or 1.61% - it’s a fairly well run country, so it makes sense that people don’t expect them to go belly up and default. Meanwhile, Argentina has a sovereign risn if 1835 basis points, or 18.35% - self explanatory.

It’s not 36.1% because hat{e} = hat{E} - pi + hat{E}*pi. Capital e (E) is the nominal exchange rate, lowercase e (e) is the real exchange rate, pi is inflation, the hats mean annual change.

My social credit score is now negative one billion

Once again, read the Russia post to read a more detailed account

Great post! I'd be remiss if I didn't say, however, that twice now, I've seen you use the word "descentralized". Unless that's some outback Australian way of saying "get the stink off a pig," I assume you've got a scratch on your internal record player and it adds the superfluous "S" every time this word spins past the needle.

I think another issue with a currency board is what do you do with the reserve and the opportunity cost.

Consider, you deposit $100 in a bank, the bank keeps maybe $10 and lends out $90. If the bank charges 10% it gets $9 in income, if it pays 5% you get $5. Great. But if you want to withdraw $20 one day, the bank is in trouble. Well no it isn't because there are all sorts of rules and systems in place to make sure the bank can pull $20 out to cover your surprise withdrawal.

But say you put in $100 and you get 100 Stablecoins. The good guy running the stable coin puts 100% of that in reserve. Now while he could have been getting 10%, he gets 0%. The temptation is really there to say "can't we lend out just a little? how about half? what are the odds half of all coins will be redeemed at once?"

But even if they resist temptation, it's still a bit of a challenge. You don't literally store billions of dollar bills in a safe. If the stablecoin becomes huge, the reserve is going to become billions of dollars. Where can that go? Short term Treasuries, money market accounts? Those are pretty safe but you still have to think about what happens when there's a run on, say, $100B of stablecoin? Even money market accounts can't spin on a dime, try to liquidate a huge amount very fast and your reserve asset could crash.

If this is really going to work and if it is really going to go big time, you are probably going to need more than 100% reserves. You probably want several different assets (say Treasuries, money markets, gold) so you don't have to crash the market by trying to mass liquidate all at once. But how are you going to make profit doing this? The opportunity cost is going to be huge and you're essentially providing a public service for the crypto-ecosystem. Either you have to tax crypto to pay for this service or you need something like a central bank supporting you willing to come in and print dollars should the need arise.