Recently, the concept of the “15 minute city” has been all over the news and social media - to some, it’s a utopian relief from the shackles of car centric design; to most, it’s a new idea; to deranged conspiracy theorists, it’s a further step on the plan to make everyone eat bugs and become genderfluid. What is the idea of the 15 minute city, and does it make sense?

Entering district one

What is the 15-minute city? Proposed by urbanist Carlos Moreno a few years back, the general idea is that it’s a city where most or all amenities (grocery stores, pharmacies, entertainment, public services) are within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. The key concepts, according to Moreno, are designing communities around human needs and not around driving, mixed use of land (combining commercial, retail, and businesses), and that people can live within a single area - which would be a more agreeable pace. The whole point is that a community built around accessibility through “active means” (walking, cycling) can satisfy most people’s needs.

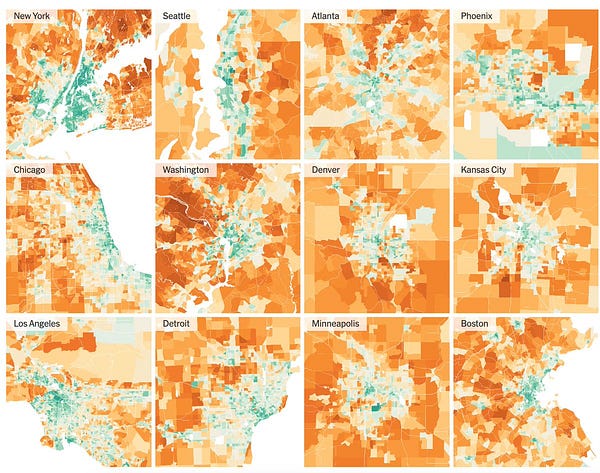

Presently, urban communities in large parts of the world, and especially in the United States are designed around cars - so that driving is the main mode of transportation. This has serious consequences on the environment: traffic congestion (woah!), air and noise pollution, and higher greenhouse gas emissions. The environmental benefits, therefore, cannot really be overstated. A 15-minute city would be sustainable because, as seen below, denser urban cores have significantly lower carbon emissions than suburbs, or than sprawling urban areas. Carbon emissions from passenger vehicles make up about half of the total, and transportation as a whole is one of the biggest contributors to total emissions as a whole. The least walkable cities have, unsurprisingly, the highest per capita emissions. Cars are, overall, bad.

Additionally, car-centric urban design has resulted in urban sprawl - the extension, over space, of cities. These spaces are usually characterized by low density, single use development (i.e. exclusively housing), and development in a scattered manner - which results in communities being less accessible overall. This kind of sprawl has resulted in an increasing distance between workers and their jobs, as well as jobs themselves spreading out from city centers, which oftentimes means that residents with more constraints in their job search tend to choose positions that are not a good fit for them, thus depressing their present and future earnings. The environmental effects, of course, are what is to be expected - pollution, greenhouse emissions, etc. Of course, more dependency on cars and more trips will increase the likelihood of traffic accidents, which are a leading cause of death in the US and contribute to its comparatively low life expectancy. And lastly, of course, low-density cities that focus on single family housing have higher housing costs, with large and negative effects on the economy overall - especially productivity.

In terms of access and mobility, the point is to remove limitations for people to perform their everyday actions and duties - in order to increase, not decrease, options for engaging in urban life. I’ve mentioned in a previous post how car-centric urban design affects women specifically and disproportionately, so this would be good. In the US, mobility and accessibility without a car is pretty low, which obviously has consequences regarding the amount of time one drives - especially since people without the ability to drive tend to be disrpoportionately poor. Of course, urban design centered around walking and cycling is not universally accessible (some people can’t really walk), so acommodations need to be made - especially involving transit and other “semi active” modes of transportation.

So overall, the idea of making cities denser and more walkable seems, in principle, decent. But would it work?

What little we know

To start, we should dispense of the notion that extremely car centric urban design reflects preferences. Firstly, it probably doesn't. Secondly, saying “it’s preferences” is more a crutch to substitute economic analysis than actual insights. Thirdly, whether or not people prefer something is not necessarily proof that it’s good - urban policy is not a popularity contest.

The main way to begin tackling this question is to look at what’s the core function of a city. Cities aren’t for fun (the greatest thread in the history of housing twitter)- largely, instead, they consist of two markets: land and labor.

Land is straightforward: buildings go on it. Since space in a city is limited, this means that the value of land is non-zero (versus, say, air) and, therefore, there is a market for it. Exactly why the size of a city is limited is an important question, but it ties with the following issue, and is key to resolving whether a fifteen-minute city is viable. How the demand for land manifests is not exactly crucial to this, but in general, certain areas are in higher demand than others, which means that the value of the land in them will be higher, and results in building more in the same space (i.e. more densely, i.e. taller buildings) to fit the highest amount of people in the lowest area possible. Conversely, less-demanded areas can have as much sprawl and as little density as desired, since land is cheaper and can be used up more - in them, building tall is not economically reasonable.

The labor market is the key reason why cities exist at all: people live in cities because cities are the only location where highly specialized trades can have enough customers to be viable, at least in principle, meaning that both buyers and sellers of, say, professional labor wouldn’t be able to conduct those trades otherwise. The economic core of a city is whichever niche, specialized services it provides, but its beating heart is the non-tradable services economy: lawyers, doctors, hairdressers, restaurants - they are in the city because the specialized professionals, and each other, demand normal goods and services, not just venture capitalist hubs or high tech rug factories. The key economic factor is agglomeration: bigger labor markets produce gains in efficiency for all participants, and this is caused by specific concentrations of activities in cities.

A city’s labor market incorporates all of them, and there isn’t really a natural limit to how many people can live in a city - as many as its economy can acommodate. Physically there isn’t really a reason why a city can’t be infinitely big, but in reality travel times put limits on this: it doesn’t seem very practical to drive 5 hours to your job. Of course, infrastructure and transportation technology can affect this - which is why the biggest cities, surface-wise, either have really efficient land use and transit, or have put in extraordinary levels of money into car-centric infrastructure.

The key issue of a 15-minute city is here: there is basically no way in which a city can sustain a large labor market that is also accessible within 15 minutes unless this refers to having a city with extremely fast, extremely reliable transit. Most cities are some mix of monocentric (i.e. have a single business district) and polycentric (have many smaller business districts), simply because there are a lot of efficiency gains to be had by renting out office space in the business district (there’s more of it), but on the other hand clusters of specific activities tend to pop up elsewhere basically randomly.

The 15-minute city model would be closer to the urban village: a city where there are districts where people both work and live. In terms of working, there is obviously a problem: cities work, economically, by agglomerating specialized activities in ways that create markets large enough for them. The problem, naturally, is that a neighborhood is not a large enough market to acommodate this kind of economic dynamic - there is simply not enough clientelle to support the kind of niche economic activities that are the beating heart of cities. There’s also the issue that certain types of facilities, such as specialized hospitals or schools, or certain amenities (museums, theaters, concert halls) require a large market to subsist, and it would be an ineffective use of resources to have overcapacity of opera halls.

In theory, then, a 15-minute city doesn’t really work beyond the daily conveniences - parks, stores, schools, etc. In practice, it’s not really feasible - most commutes aren’t very functional in this modality even when excluding big-ticket commute items such as work and school. Generally, most attempts at developing urban communities where all members lived and worked in the same area have been unsuccessful: people who need jobs can usually not afford to move, and people who buy houses probably have jobs elsewhere. Likewise, there is a strange paradox in some nations, such as Spain, where the closer to work people live, the less accessible everyday services are - probably due to job sprawl and the fact that denser cities have more accesible central business districts. And in terms of what services are actually accessible, it seems that even moderately well planned cities have their residents covered - 94% of Parisians live within 5 minutes of a bakery, and 94% of Mexico City residents can walk 5 minutes or left to a taco shop. Talk about living the dream.

Conclusion

Summing up, it doesn’t seem that a 15-minute city (or 30-minute city, even) concept is very economically sound as a whole. However, the central ideas that cities should focus less on cars, less on sprawling single family development, and less on prolonged commutes are all good, and should be taken into consideration - especially when including expanding and improving transit, a net environmental positive. These would be improvements to both economic efficiency and economic inequality.

15-minute-heads, I love you, but you are not serious people.

I think "15 minute neighborhood" is a bit more accurate than "15 minute city."

Great piece. While I agree that it's probably not practical for everything to be within a 15 minute walking distance, I think we can get most of the way there.

If we tax land values instead of property and adopt form-based codes over Euclidean zoning, the city businesses and inhabitants would probably arrange themselves into something resembling the core goals of a 15 minute city.

Crucially, this can be done without any form of central planning.