The curious task of economics is to demonstrate to men how little they really know about what they imagine they can design.

Recently I finished reading Alain Bertaud’s “Order Without Design”, a book that has a pretty simple premise: what can urban economics contribute to urban planning? It’s an amazing book full of interesting insights, although a bit dense and hard to read more than one chapter at a time. I very much recommend it.

A tale of two cities

Every step and every movement of the multitude, even in what are termed enlightened ages, are made with equal blindness to the future; and nations stumble upon establishments, which are indeed the result of human action, but not the execution of any human design.

Washington D.C. is one of my favorite cities. It was designed in the 1800s to be America’s capital by L’Enfant, an egotistical urban planner obsessed with aesthetics. Brasilia is a city that I really want to visit, and it was planned in the 1960s to be Brazil’s capital by architect Lucio Costa, following the ideas of egotistical urban planner obsessed with aesthetics Le Corbusier.

The main difference between Brasilia and DC is that people absolutely love Washington, but DESPISE Brasilia. American politicians get called out for spending too much time in the DMV (DC-Maryland-Virginia), while Brazilian politicians get called out for flying out to Rio or Sao Paulo every weekend. I was talking with Americans at a conference I was at recently, and they all said how nice it was that you could walk everywhere in DC. Meanwhile, I talked about Brasilia to a few people who’d been there, and everyone hated how far away everything was, how there were no trees anywhere, and how all the buildings and blocks were gigantic.

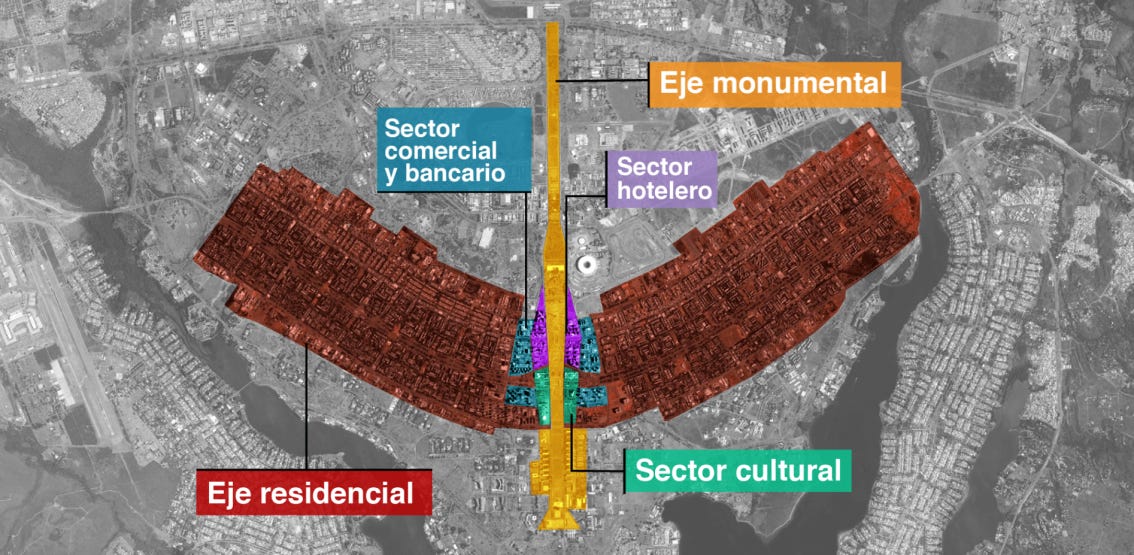

The main difference between DC and Brasilia is that DC was planned very lightly, and Brasilia was sketched out in painstaking detail. Whatever his flaws, L’Enfant mainly stuck to designing where all the major streets would be, all the important buildings, and parks and squares so people could enjoy green spaces. Meanwhile, Brasilia’s planners decided what every inch of the city could be used for: certain parts for suburban dettached-style housing, certain parts for restaurants and retail, and a “monumental axis” with all the workspaces. On top of that, the city was built around the idea that everyone would have to own a car and have to drive everywhere, which in the 60s was considered cool.

In reality, people don’t like having to drive 40 minutes to get coffee, and they don’t like having to get stuck in hours of traffic and an eternal search for parking every single day while they go to work. The city also doesn’t have pedestrian crossings or stoplights, which is both insanely dangerous and also ludicrously stupid - people have to cross the street somehow, which means traffic grinds to a halt every single time anyone does. Lucio Costa himself later said that people shouldn’t maintain the original design of Brasilia, but the city is now a world heritage site, so tough luck.

The city was so atrociously planned that, out of an originally intended 700,000 people (max population), only about 200,000 moved in; most of the Brasilia metro area’s 2 million and change inhabitants live in the suburbs, which weren’t designed by deranged maniacs who wanted to tell everyone how their houses should look like. But this isn’t a Brasilia-specific issue: other planned 20th century capitals, like Canberra or Islamabad, also seem to be uniformly hated by everyone who lives there, and other SIAM fever dreams like the Bijlmer follow suit. Le Corbusier himself even tried to tear down all of historical Paris to build giant concrete skyscrapers, but everyone hated the idea so much it went nowhere (well, actually to Buenos Aires, and then nowhere).

The point to be taken here is that utopia isn’t possible and it’s dumb to try to build one: even if a bunch of complicated charts tell you that a city should have all its amenities incredibly far away from houses, and that people want to drive everywhere for hours instead of taking the bus for 15 minutes, you can’t know you’re right because you don’t know better than everyone. The fundamental, non-wonky point here is a Hayekian one: cities, like any other large economic system, are very complex and have buttloads of interactions within them.

If you say “such and such place should have such and such building”, you are in fact setting rules for the game of the urban economy that people respond to, rationally, to their maximum profit. If you set up an economy where driving around everywhere and being a selfish racist jerk are optimal, people are going to do that, and other people who either don’t live in the city or live in Africa and are going to starve to death in 20 years because of drought have to deal with the consequences. A country is not a company, and a city is not a big building. Cities, after all, are closed systems: if you want a parking spot, you personally can arrive earlier and get one. But if everyone did that, the parking lot would just fill up earlier. Same thing happens with cities - you can’t build one like a big building because there are lots of people in them, and many people mean many complicated things going on.

Drawing up the market

Cities are places for people to do people stuff, but for economists, they’re fundamentally two big markets: labor and land.

Land is easy: buildings go on it, and it’s not unlimited. Depending on how many people want to use a given patch of land, it goes up and down in price. Density, i.e. how many people live somewhere, is determined by land prices: in some places, building really wide buildings is profitable, and in others, building really tall ones is, and this depends on how expensive it is to put up a building on the land. If you set rules about width and height that don’t take this into account, you end up with wildly unproductive land use, and everyone has to pay the price. DC has pretty bad regulations on this, because places that are like 10 minutes away from major economic centers just have big houses for single families - in the middle of the city.

The market for labor is more complicated. People live in cities because there are other people in them, and those people live in them because there are other people in them, and so on and so forth. For whatever reason, usually geography or historical happenstance, a city has a unique economic advantage in something, and people who work there move there because it’s profitable. But because there are well paid people in that place, others flock to be their (also highly paid) doctors, hairdressers, lawyers, etc - so most people work in normal stuff, and a couple on the high-end things. The economic advantage of cities comes from agglomeration: the bigger the labor market is, the more opportunities to just sell regular services become, and the bigger the benefits for the high-end industries. So land use decisions can have enormous consequences because they determine how many people live in a city, and therefore how big the economic benefits of living in one are - for everyone.

I’ve talked about this a trillion times but basically everything that matters to anyone gets a visit from the housing fairy:

economic growth in the US was 36% lower due to housing regulations in just three very productive cities, and made productivity lower as well

wealth inequality is fundamentally a housing ownership issue, and inequality in housing explains most inequality in wealth

since the US government has historically been very racist, the people who own houses are all rich and white, and the people who don’t aren’t.

the decline of socioeconomic mobility is related to people being unable to move out of bad cities into good ones, because the good cities build no housing and therefore are too expensive for regular people

most urban planners are and have historically been men, which leads to cities being built around a 6ft height (which is tall for men) and around cars, which are mostly driven by men

because the largest contributor to climate change are CO2 emissions from transportation, urban density is vital for climate action

the people who are most outspoken on housing issues are rent-seeking homevoters who want their houses to be more valuable, which is antidemocratic

(wonky one) because labor markets are disconnected, choosing when to heat up and cool down the entire economy gets harder, which means that monetary policy becomes less effective and also more risky

Another tale of two other cities

So housing is very important and regulations have tended to be bad. Does that mean there should be none of them? No!

For once, things like fire safety regulations and historical preservation are very important - even though there are discussions to be had over what kind of safety features and protocols are cost-effective at saving lives, or whether or not places like parking lots and laundromats deserve historical status.

The thing here is that, fundamentally, many economic regulations are ultimately about values and not about wonky technocratic stuff. For instance, antitrust economics argues about something called the consumer welfare standard, which I’m not going to get into because I don’t care about it and it’s way too complicated. But some economists disagree and want to change it to a standard that promotes worker’s welfare, or competition, or whatever. Either way, there are different groups accruing different costs and different benefits - a proposed antitrust standard would be that all mergers be allowed because the owners of the mergees would profit from them. “I support cost-benefit analysis” is an empty statement because costs and benefits accrue to different people. Everyone is greedy, and it comes down to whose greed is frowned upon and whose greed is acceptable.

With that in mind, consider Paris. The city is insanely expensive (renting out a one room apartment costs 750 dollars a month) because it has ludicrously strict historical preservation regulations, plus height limits, plus rules on what buildings can look like, plus things like height caps to preserve the views of famous buildings. The reason why Parisians have these rules is that they want the city to look like it’s still in the 1880s so tourists will spend money to go there. And while, as a tourist, I prefer these nice vistas, I also think Parisians would be better off by not having to live in uber-distant suburbs. But while Alain Bertaud, the book’s author, disagrees with these regulations too, he thinks they’re good at what they do (and I do too), because they take a single goal and achieve it in a cost effective way (not all of Paris has the same regulations).

Meanwhile, New York is also a ludicrously expensive city with very stringent housing regulations, but the reason these regulations came about is not precisely clear to anyone in particular. Sometimes it’s because the city used to be insanely racist, other times it’s because the city was insanely racist but the other way around, then because rich white people don’t want their houses to not be very expensive, or because they want the city’s developers to pay for public services like subsidized housing or plazas. The thing is, these regulations are bad not because they make housing more expensive, but because they follow no rules about why they’re being put into place - instead of order without design, we get chaos with itemized building codes.

Conclusion

Rules have to take two things into consideration; first, their purpose. Rules have to follow, well, rules about who benefits, what the cost is, and why - so you actually do get an orderly set of norms that anyone can follow. Secondly, because people have to follow these rules, you have to take into account the complexity of human society and how people will follow the rules not the way you want them to, but the way that’s beneficial to them. Just focus on stuff like where the important stuff is and not having slums, and leave where stores are and what they look like to the free market.

Also Le Corbusier and Robert Moses are SATAN INCARNATE.

Very good piece and insightful as well in combining economics and urbanism (which i love); I will definitely try to read Bertaud. Although, living in Brasília myself I'd only correct your description of Brasília about the lack of pedestrian crossings and stoplights: it is not true for both cases, but I understand where you're coming from.

Regarding the first one, it is often conveyed in media outlets to be a matter of pride and high regard among locals that this is a city that respects pedestrian crossings the most, and I find it empirically true in my experience in other brazilian cities. The same is true for stoplights, not in the pride and admiration department, but in that they are very common throughout the city.

I assume the mistake stems from one of the road axis, called Eixão, not having pedestrian crossings or stoplights, but it's the only axis (and street/road) to be designed like that, and very-very-low-key kind of makes sense in its absurdity haha. But the other axis, Eixo Monumental, does have stoplights and pedestrian crossings. Whereas the lack of pedestrian crossings in Eixão is true, they do have semi-underground pathways for pedestrians and the problematic issue orbitating it for the last couple years have been the utter precariousness and neglec by public authorities that entails pedestrians in hazardous situations and proclivity for muggins.

Congratulations again!

Very Interesting piece!