Farmwork, housework, office work

Why, how, and when women left and then rejoined the labor force

One of the biggest social changes in recent history was women rejoining the workforce, more and more since the 1960s. Surprisingly, women actually had only left it fairly recently, as late as 50 years before second wave feminism. Why did this happen? Were there any other causes? I mostly focus on the US, because of the extensive scolarship in that regard.

This follows somewhat in depth posts about female labor participation (in Latin America), the wage gap between men and women, so be sure to check those out as well!

The long arc of women in the workforce

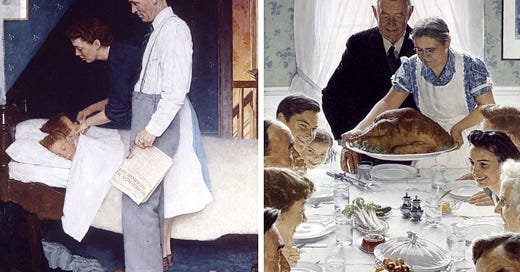

In the past, people used to mostly work in agriculture, which requires a lot of labor. As a result, everyone - even women - worked in the fields, so women were deeply embedded into the workforce, even in the most traditional societies. Once the Industrial Revolution came about, families could be supported with a single income but housework needs were enormous, so women got the short end of the stick due to social norms and had to progressively leave the workforce.

However, as societies got even more prosperous, and various technologies that saved domestic labor were invented (refrigerators, washing machines, dishwashers, etc), then people required more income and less domestic labor. Additionally, prosperous societies also educated women, which meant that they had even greater opportunities to earn income. Economically speaking, this resulted in women rejoining the workforce after technical innovations became accessible enough and they were educated enough for that trade to be appealing.

As a result, as standards of living continue to rise, necessary spending on various goods and services (childcare, babysitters, etc) continues to grow, and women’s educational attainment in rich societies is generally greater than that of men, so their integration into the workforce intensifies given adequate environments.

Why did women drop out of the workforce?

That woman was the slave of man at the commencement of society is one of the most absurd notions that have come down to us from the period of the Enlightenment. (...) Woman occupied not only a free but also a highly respected position. (...) As wealth increased, it (...) gave the man a more important status in the family than the woman.

Friedrich Engels, “The Origin of The Family, Private Property, and the State” (1884), redactions by Claudia Goldin.

It’s difficult to generalize because of the scarcity of data, but as a rule, women started changing their lines of work and the timing thereof as time went on, due to various factors such as lower mortality rates and professionalization of the workforce. It can be safely assumed that married women or women with working-age children participated much less, but that single women or female heads of household tended to work, either in a home “business” or for wage work. Now, there’s not really evidence backing the “golden age for women” refrain, but there is evidence backing that women were somewhat likely to be in the workforce.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the United States was still a very agricultural nation, so women generally did unpaid work in their family’s farm. Industrialization changed the structure of employment; firstly it boosted female labor, because the kinds of work that only a skilled (male) craftsman could do, would be performed by a less skilled woman. But as the US urbanized more, these job opportunities started vanishing, and women who worked were generally very poor ones or heads of households. Regardless, plenty of women worked in some sectors of manufacturing, helped with their husband’s businesses, and entered professions such as midwivery, teaching, or nursing.

From the late 19th century to the 1920s, women who worked were generally in manufacturing or services (retail, domestic labor, etc) and didn’t have (or require) much education, with little benefits to education, learning, or experience. Jobs were unsafe and unexciting, so all but the poorest women (and some very highly educated ones) left the workforce after marriage. Clerical workers were generally men, and those were seen as key ancilliary positions that could provide a launching pad for a promising career. Teachers, nurses, and midwives were disproportionately women, and their high level of education allowed some permanence in the workforce.

Later, by the mid 1920s, since education became more common for women, they started entering service professions and especially clerical positions. Women, however, were paid less, and clerical work went from being a respectable first step in management to a dead end for working girls who hadn’t married yet. Women were still expected to leave the workforce after marrying, although some returned once their children grew old enough to attend school. Three quarters of employed women were single in 1900, and the average age of a working woman was 20 years old; by the late 40s, these numbers only moved to over a majority and 23 years.

Plus, starting in the 1920s, married women started being barred altogether from working in certain occupations - most notably teaching, but in various high-paying clerical sectors such as banking as well. Besides social norms and whatnot, a common rationale was the expectation that a married woman would not work consistently or perform adequately, as well as the expectation that married women would get pregnant and raise their children. However, most companies and businesses who used marriage bars simply didn’t give any explanation for them. Tenure related earnings rising too rapidly was probably a leading concern, since clerical labor doesn’t increase in productivity as much. Many companies did give bonuses to departing women, and some states only barred hiring already women, but not retaining female employees after they got married.

The benefits to firms (and schools) were to reduce firing costs and to pay lower clerical salaries; the costs were increased hiring and training costs - which were lower because of the aforementioned skill requirements. As Goldin (1988) puts it, “Experienced female workers, in the majority of offices, were easily replaced by female high school graduates”. Plus, marriage bars were implemented somewhere around the Great Depression, were unemployment was high enough that competition for jobs was fierce, and were relaxed in World War Two to help fill vacancies; but when the post-war labor market tightened, their costs increased relative to the benefits.

Engines of liberation

“The housewife of the future will neither be a slave to servants or herself a drudge. She will give less attention to the home, because the home will need less; she will be rather a domestic engineer than a domestic laborer, with the greatest of all handmaidens, electricity, at her service. This and other mechanical forces will so revolutionize the woman’s world that a large portion of the aggregate of woman’s energy will be conserved for use in broader, more constructive fields.”

Thomas Alva Edison (1912)

We sort of know why women left the workforce: after industrialization shifted work outside the home, repressive social norms pushed married women back into the household. Formal policies and legal norms both clearly helped keep these rules in place. But why did women return to the workforce, especially married women? There’s a handful of factors in the 1950s to 1970s that provide explanations.

Firstly, part-time work became more common, so women could continue working while their children were younger by not working a full day. The tighter labor market after the Depression ended allowed for the end of marriage bars, and married women were generally welcomed into the workforce for their politeness, good demeanor, and more responsible attitude. But women generally still acquired most of their skills before entering the workforce, and acted as secondary earners - their decisions depended on their husbands’ plans. Women had jobs, men had careers - and the first question any “professional” woman was asked was “how well do you type?”.

Plus, women started being more and more educated. Mandatory secondary education was a big factor, which took its time to fully materialize. Plus, a small but significant percentage of women started attending higher education, generally as a way to meet a high-income husband, either directly or by entering a better paying field; but later, those women still started trying to return (or enter) the workforce anyways.

In addition, women whose mothers worked were more likely to work themselves, and men whose mothers worked were more likely to accept (or want) a working wife. Since World War Two presented a variety of worker shortages, and a tighter labor market reduced the appeal of marriage bars, then many more people were accustomed to working women. In this period, adult women started marriying later and thus could expect more and more of their remaining life to be spent in the workforce, so this phenomenon self-propagated. Young women started expecting that they would work for more of their adult years, so their college attendance and graduation levels improved significantly. Even female high schoolers started changing the way they approached their studies, emphasizing maths and science more and working harder and harder. Their planned career paths started changing, from teachers and nurses to other more “male” professions (lawyers, doctors, etc), and they started valuing financial success and personal independence to almost the same level as men did, in detriment of family formation ambitions.

One factor that both allowed the delay in marriages and reduced time spent raising children was the invention, dissemination, and legalization of contraceptives, commonly known as “the pill”. Birth control pills being available for young, unmarried women after the Griswold vs Connecticut decision meant that women could have a more active and longer dating life before marriage, which delayed the age of marriage significantly. In fact, about 37% of this delay can be explained just by birth control, and a third of the increase in female labor participation can be explained by it. Other family planning improvements, and changes such as the popularization of condoms and the progressive legalization of abortion, had smaller but similar effects.

Additionally, unilateral divorce started becoming more common in this era. Divorces allow for a division of property between household members, transfers of income, and can serve as a “bargaining chip” in household discussions. Think of it in the way a union would use the threat of a strike while negotiating wages and conditions with employers. Common property, generally of a home, was an enormous factor; among homeowners, female employment increased, but less than for renters. Easing divorce reduced the expected duration of a marriage, so they increased the value of spending time outside of it; plus, this increase in value of outside options made acquiring education and skills more valuable. This effect is also seen for women who aren’t married, probably because of the increased value of having skills and experience.

“For ages woman was man’s chattel, and in such condition progress for her was impossible; now she is emerging into real sex independence, and the resulting outlook is a dazzling one. This must be credited very largely to progression in mechanics; more especially to progression in electrical mechanics. Under these new influences woman’s brain will change and achieve new capabilities, both of effort and accomplishment.”

Thomas Alva Edison (1912, cont.).

Finally, there’s changes in technology. Mass electrification and various technological advances allowed for a host of labor-saving and labor-enhancing devices to be adopted in households. Before, food had to be prepared before every single meal, usually shortly after acquiring the ingredients; cleaning and laundry were arduous, time-consuming chores. New appliances like washing machines, refrigerators, vacuums, etc. changed all of this. And their prices decreased substantially after the 1950s, meaning that not only the richest could afford all of these newfangled widgets.

If we expect households to sort of act like a company, with specialization of tasks based on comparative advantage, then it would have made sense for one person to stay at home and one to work when housework was time-consuming and arduous. But replacing domestic work with goods, such as appliances, has two ramifications. First, it reduces the relative value of specializing in domestic labor, since there’s just a lot of idle time. Secondly, it increases the relative value of labor market work, since those goods require money to buy and maintain and domestic labor doesn’t earn anything. Added to women’s increased work experience and skill level, these inventions helped ease the transition into the worforce.

The final chapter?

Since the 1970s, women in the United States rejoined the workforce at breakneck speed. Their relative wages went up: while 60s and 70s feminists talked about 59 cents on the dollar, the talking point was updated to 77 in the mid 2000s, and 83 in the present. I have explored this phenomenon in further detail in a previous post, but will gloss over it briefly once more. There’s three interesting and novel phenomena at play. The first is an upwards shift in the age structure of female employment. The second, a shrinking but persistent wage gap. And the third, a stagnating participation rate.

Let’s start with the wage gap. The gender wage gap is the difference between what women earn and what men earn, measured by the typical worker (using medians). The wage gap is primarily a problem for older and more educated women, who are generally richer. There is barely a wage gap among younger people, for example, and there’s a very small one at the lowest percentiles. Across race groups, those with lower average earnings (such as Blacks and Hispanics) have smaller wage gaps across percentiles, whilst richer racial groups (Whites and Asians) have much larger ones. Discrimination and unobservables such as productivity play a role, but they’re hard to gauge, detect, and measure. Facts generally don’t point to differences in performance existing, and to discrimination playing a relevant enough role.

Firstly, there’s the gap between occupations. The most male-centric degrees, like finance or STEM, are also the highest paying ones; since women tend not to choose them, that contributes to the gap. Ignoring natural ability, young female students are generally less incentivized to consider those fields, and the disparity in performance between boys and girls only appears in roughly the third grade. Plus, a disproportionate fraction of women who work in those fields and leave them cite the hostile, masculine-centric culture as a reason. But this gap only explains about a third of the difference.

Thus, two thirds of the gap between men and women is caused by differences within industries. This is twofold. At most ages, women have substantially less experience than men. This isn’t because women are “lazy”, but rather, because women are vastly more likely to take interrupt their careers for over a year than men, generally to care for children or other relatives. There is a “motherhood penalty” for women, because those who don’t have children usually don’t have much of a gap in earnings with men of similar characteristics. But women also work fewer hours, which is the other part of the problem. There might be an occupation component, because women disproportionately work part-time jobs, but that’s a lower-income problem where compensation isn’t all that different. The real deal, at the highest income levels, is that high-earning professions disproportionately reward workers that put in long hours, suddenly and with little flexibility. Those tend to be men, since women do much more house and care work at all income levels.

Women in the US are working longer, and this is driven by older women remaining in the workforce for more time. This is driven by a variety of factors. Firstly, men are also working longer, and couples like to retire together. Both of these are influenced by the extension of a person’s healthy lifespan, meaning that working through your 60s is now easier for both genders. We know part of this phenomenon is caused by older women being more educated, and by their careers being different and allowing longer stays in the workforce, but the rest of the explanation isn’t really known; perhaps cultural shifts have an answer.

But in general, the United States is lagging behind other rich nations in female labor participation. The differences appear mainly to be related to participation-facilitating policies. Parental leave, better conditions for part-time workers, anti disrcimination measures, etc have been implemented in other developed countries, but not the US. The main weight around the US labor market’s neck, however, appears to be the high cost of childcare and the lack of policies to aid in its financing. A particular form of childcare the US often lacks is the one labeled “early education”.

Sources

The long-term trends

The exit from the workforce

Goldin (1986), “The Economic Status of Women in the Early Republic: Quantitative Evidence”

Costa (2000), “From Mill Town to Board Room: The Rise of Women's Paid Labor”

Goldin (1988), “Marriage Bars: Discrimination Against Married Women Workers, 1920's to 1950's”

The return to the workforce

Goldin (2020), “Journey across a Century of Women”

Engemann & Owyang (2006) “Social Changes Lead Married Women into Labor Force”

Goldin (2006), “The Quiet Revolution That Transformed Women's Employment, Education, and Family”

Stevenson (2008), “Divorce Law and Women’s Labor Supply”

Greenwood, Seshadri, & Yorukoglu (2000) “Engines of Liberation”

The final chapter

Goldin (2014), “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter”

EPI (2016), “What is the gender pay gap and is it real?”

Blau & Kahn (2013), “Female Labor Supply: Why is the US Falling Behind?”

Goldin & Katz (2016), “Women Working Longer: Facts and Some Explanations”