What is the wage gap?

In the United States, women made 18% less than men on average. This gap is larger for non-white women, and is not static between income levels and throughout a woman’s lifetime. Additionally, this gap has shrunk since the 1970s, when it was 41% - but gains have been made at a slower and slower pace. It is worth noting that it is possible for the wage gap within minority groups (for example, black men and black women) to be smaller than the wage gap between white men and women of color, probably due to lower wages among minorities generally.

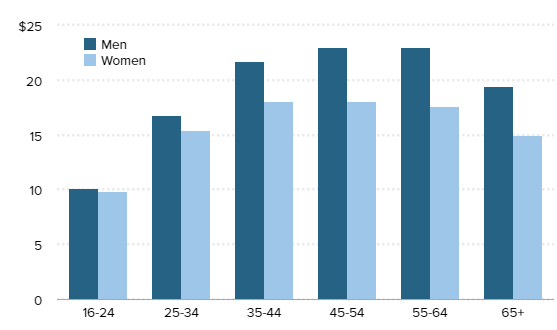

An interesting pattern is that the wage disparity actually increases thoroughout a person’s working life - younger women make about as much as younger men, and the disparity emerges around the early 30s and widens for the following decade or two. There actually is evidence that there might be a wage gap even at the youngest ages, but regardless it is expected to increase throughout a person’s life.

Finally, the third component to explain is that the wage gap, in general, grows alongside income, meaning richer women make more than poor women but at a smaller fraction than what men make. In fact, the 95th percentile has the largest wage gap of them all - women in the top 5% of incomes make more than a quarter less than men for every hour they work.

Wage gaps between occupations

The wage gap isn’t caused by different rates of colleged attendance, because women are often more educated than men in general - the difference can’t come from the college wage premium. In fact, the wage gap for educated women is largest, since they make 73% of what similarly educated men do.

Firstly, men and women don’t choose the same career paths between and within professions. For example, nursing is a disproportionately female occupation, while computer programming is a disproportionately male one. As a result, if the career paths women choose have lower salaries than the ones men choose, then there will be a disparity in wages - all factors being held equal. This is known as the wage gap between occupations - i.e. the differences that arise from career choice.

This should explain part of the story - many of the lowest paid college majors are disproportionately female and many of the highest paid are disproportionately male.

But why don’t women simply choose STEM or finance more often? Besides from the actual demands of the job (more on that later), they are frequently far less interested in STEM or business. Only 14% of women are interested in STEM, for example, compared to 39% of men. And women are substantially less likely to be “groomed” by their parents and teachers towards such degress. For example, there is evidence pointing to the gap in performance between men and women in maths is narrowing, and that girls in more “traditional” places have lower maths performance.

This doesn’t even mention that industries perceived as “boy’s clubs” are less attractive to women, who don’t want to work with obnoxious men (but who does?). Regardless, career choice just isn’t that big a deal, since the within occupations wage gap only explains 32% of the difference. An interesting part of the wage gap between occupations is that women disproportionately work part-time (25% of women vs 12% of men), which results in pay that is 9% lower than women who work full time.

Wage gaps within occupations

Put another way, 68% of the gap between men and women is caused by the differences in pay within occupations, and not between them. Where does that gap come from? Mostly, from hours worked and interruptions in careers. For example, among MBAs, women with children work 24% fewer hours than men and women without children (who work roughly equal hours). Given that many careers reward workers for working very long hours, especially on weekends, it could be that women opting to take care of their children instead of working puts them at a disadvantage to their male colleagues.

It is painfully obvious that the kind of high-achieving women who go to business school would love to work the long hours men do, but don’t because childcare is generally a “gendered” task. Housework is a burden that disproportionately falls on women, and it explains about 14% of the wage gap. There isn’t a housework-related pay gap for unmarried men and women, meaning that this gap comes from married women having to perform domestic work much more than their (frequently male) spouses, reducing their chances of working longer hours. As a result, women with children make 5% less than women without them, and there isn’t much of a wage gap between childless women and men.

Moreover, women have less job experience than similarly-educated men of the same age. This isn’t because women simply like working less than their counterparts, but rather because women are far likelier than men to leave the workforce temporarily, to look after either their children or an elderly relative. Again, these are tasks that are disproportionately gendered - among MBAs, only 10% of men stopped working for over 6 months after a decade in the workforce, compared with nearly a third of women.

Discrimination

So far, we have seen that a large part of the wage gap is due to career choice and time allocation. But is there a component that is just outright discrimination?

Well, not even the first factors are free from discrimination. It’s clear that women are generally less incentivized to be interested in STEM or other similar high-paying fields because of social expectations, which also have an influence in their actual performance in those fields. Besides, women may simply not choose to enter fields where men are unpleasant towards their female coworkers - for example, a majority of women in STEM who left their job cite either hostile job environments or excessive work hour requirements. Since large, high-paying firms and sectors disproportionately rewarding those who work long hours without interruptions in their work harm women because of the large burden that housework and care impose on them specifically.

Additionally, when women enter male-dominated professions, they may not actually make more money - they tend to earn less than their male counterparts. This effect is large enough that, even if male-dominated industries might pay more, women who go into them earn as much (if not less) than women who work in female-intensive industries. And once women begin entering a profession at a large scale, that profession tends to have substantially lower wages a decade later, mostly due to “devaluation” of tasks done by women.

Beyond this, measuring discrimination directly is hard, but it is clear it exists. An infamous example is the orchestra auditions experiment, where women became far likelier to be hired by orchestras if the auditions were carried behind curtains. All else being equal, recruiters are more likely to call back for interviews men to women, especially if the women have children. Finally, people rate the job performance of women as worse than that of men, and mothers as even worse - despite women being as productive as men and women with children being more productive, not less.

Conclusion

Between 1979 and 2015, the wage gap shrunk from 48% to 18%. However, about a third of this reduction was caused by men’s wages growing more slowly. This follows women’s increased educational attainment and labor force participation, which resulted in their incomes going up (for example, the educational attainment component of the gap was obliterated by the 1990s).

This follows a change in the labor market integration of women, who (until the 1940s) stopped working after marriage, with rare exceptions such as nurses and teachers. After the 1940s, unmarried women participated in the labor force roughly as much, but married women started joining it. This was due to both the creation of modern structured part-time work and to numerous domestic labor-saving inventions, such as washing machines and refrigerators, that incentivised labor market work in exchange for less domestic labor. This trend continued into the 1960s, when women began joining employment in large numbers as well.

During the 70s, a “revolution” began. First, women started expecting to work, instead of expecting to become homemakers. Secondly, women’s college attendance rates skyrocketed, surpassing men by the late 80s - and the dissimilarity between majors was narrowed significantly as well. Women’s attachment to the workforce also increased, with them valuing making a family less and their financial status or professional success more. There are many factors explaining this shift: women started getting married later and having fewer children at an older age, leaving them more time to work before settling down. This last part was specifically enabled by a single invention - the birth control pill, plus the more widespread use of contraceptives.

There was a slowdown in progress made by women since the 1990s, probably due to a weaker labor market. This slowdown in progress came in both labor participation growth, employment, and occupational segregation (i.e. how many women work in male-dominated and equally gendered professions), and has affected women of all genders and ages. Part of the reason for the reduction in wage gaps is the equalization of unionization rates, driven mostly by the decline of unionization in (disproportionately male) blue collar work, plus some overwhelmingly female industries becoming unionized (nursing and education, for example).

I really liked this blog - but - are you familiar with criticisms of the orchestra study? https://statmodeling.stat.columbia.edu/2019/05/11/did-blind-orchestra-auditions-really-benefit-women/ Gelman went through it - basically, it's results are massively overstated.

Genial, muy bueno!!!