The US is facing its highest level of inflation in 40 years or so - and ending the Great Inflation required interest rates of nearly 20%. Why is inflation so high - and is there a risk that only a recession could stop it? This post will have two parts: in this one, I’ll focus mostly on why inflation went up so much and dissect some (bad) narratives around it - the followup will focus on solutions to inflation, monetary policy in 2021, and why I don’t think a “Powell Shock” is likely to happen.

Inflation as a four letter word

Why is the US suffering from such high inflation in the first place? There have been many bad narratives around it: low unemployment, specific prices going up, “it’s just oil”, the stimulus, the Fed printing money, etc. Neither of the three are actually right, but let’s start with a good narrative and move on to why the other ones don’t really make sense.

Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon, in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.

This famous quote by Milton Friedman does a good enough job explaining what inflation is: too much money chasing too little stuff. If you give a million dollars to every single American, nobody would be any richer after enough time, because eventually prices would go up enough to offset the million dollars. An especially quick reader might say: “but isn’t it what Biden’s stimulus did?”, and yes, we’ll get to that. But what “too much money, too little stuff” ends up meaning is that there’s an excessively high level of (nominal) demand for any given (real) supply. The economy, at any given time, can only make so much stuff - which means that it can only support so much employment and therefore so much spending given the characteristics of the labor market, various policies, technology, etc. This is fairly easy to understand through the quantity theory of money (well, technically the equation of exchange): MV = Py. “MV” is the amount of money being spent, in nominal terms; “Py” is the amount of stuff being purchased - P is the price level and y is the real volume of stuff. You can read more about the theory in a fairly recent blog post of mine.

It is generally agreed upon that controlling inflation falls under the Central Bank’s purview. The Central Bank (or “The Fed”, for the US) is also tasked with maintaining employment - and it’s somewhat commonly believed these two goals are at odds, when in fact they complement each other. Let’s go back to MV = Py. If “MV” (aka “spending”) is too low, then both inflation and employment will be too low - and, conversely, unemployment too high. People spend too little money, ergo too few people have jobs selling or making the things they spend money on. Now what happens if MV is too high?1 Well, traditionally it was believed that unemployment would be too low and that either inflation would make real wages lower or that wage growth would push prices up. But I don’t really think that more inflation is stimulative simply because the amount of jobs in the economy ends up depending more on “y” (aka real supply) than on “Py” (aka nominal supply, which equals nominal spending). But this is a minor point, and doesn’t change much the implications.

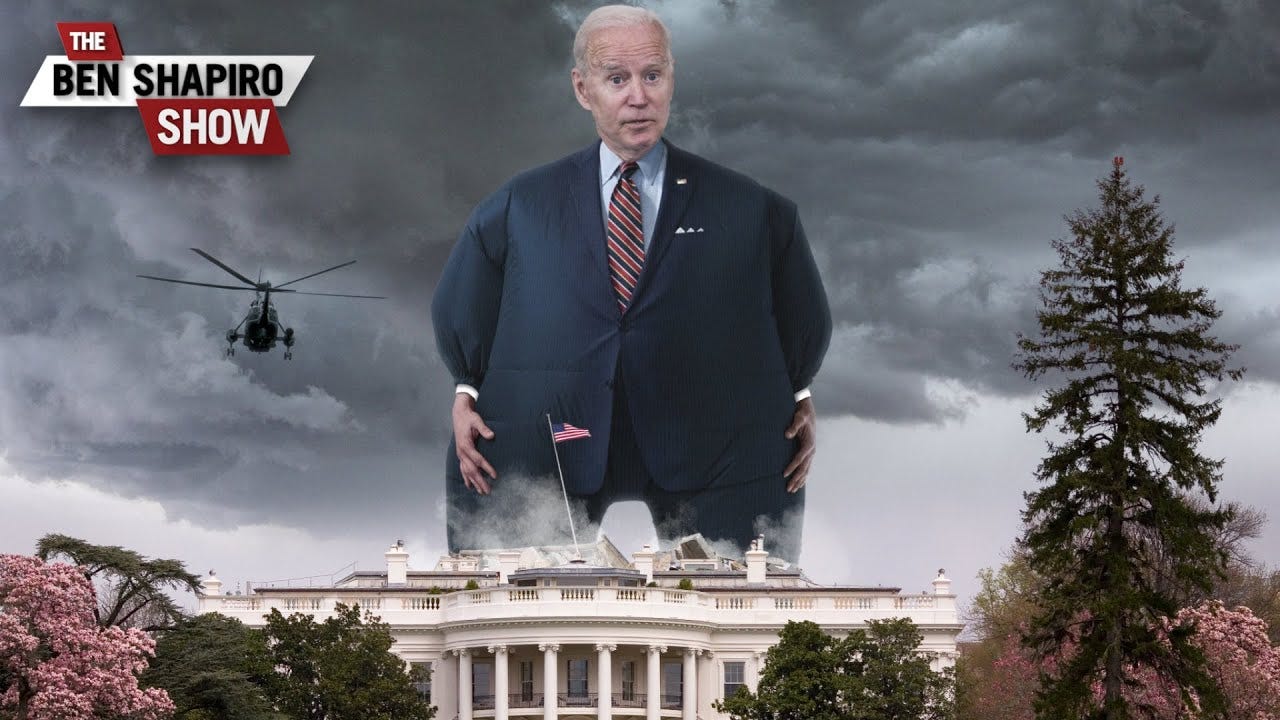

A big one is that, then, the most relevant indicator to how the economy is doing isn’t interest rates, it’s the total level of spending, or NGDP (Nominal GDP, aka “Py”). Interest rates don’t tell you anything about monetary policy because, for instance, a 5% rate is deflationary (i.e. causes a recession) with 2% inflation but inflationary with 10% (or 25%, ask Turkey). Real interest rates are better, but of course the information is outdated by the time decisions have to be made, and expected inflation isn’t that easy to forecast either, so most forecasts aren’t very good (and also depend on expected interest rates anyways). So you can get a generally good idea of how high spending ought to be by estimating maximum possible NGDP and then seeing how big the gap between actual and potential looks like - and it looks like this:

Both too much NGDP and too little NGDP are bad, for example, take the 2000s: the Fed didn’t do enough to get spending back on track, the Treasury either, and what happened was that total spending didn’t get back to the maximum level until the Trump administration. That’s not good. Likewise, spending fell off in 2020 (because of the pandemic) and then rebounded and got back to the levels it would have been without the recession by mid 2021. However, then demand kept going, and now it’s 3.4% above the level it “should” be.

Too much money or too few stuff?

The NGDP approach accounts for both supply and demand shocks. A demand shock is too much demand (think, everyone finds a hundred bucks in their couch at once) or too little (a recession). They’re fairly easy to respond to: more money. A supply shock, however, happens when the economy either makes too many things (think a new invention that raises productivity), or too few (think, oil shock or crop failure). Negative supply shocks, as I’ve written before, are a real pain. The reason is simple: you have at the same time less stuff and more (relative) spending. This means that inflation and unemployment go up at the same time, so monetary policy doesn’t have a clear path forward, unless you have a mandate only to control just inflation or unemployment.

You can get that a supply shock occured because NGDP can actually increase - take, for instance, housing. The US is supply-constrained there, because it’s not legal to build enough housing in most of the country. Ergo, people have to pay a lot for houses. This can be reflected as either higher prices for the same housing, or less spending on other things and more on housing, or buying less housing for the same price. NGDP remains constant in two of the three cases - and actually goes up on the first. In the cases where NGDP doesn’t go up, spending in housing either doesn’t change or is compensated by spending on other things, so inflation doesn’t change much - however, in the last case, inflation actually goes up2.

I’m gonna come back to this in a bit, but the US had a highly stimulative policy, spending on services collapsed because of COVID, and issues in Asia, plus uniquely American regulatory issues (tariffs, port zoning and automation, stuff like whatever the hell the Foreign Dredge Act is) meant that there suddenly was a lot less stuff to go around and a lot more money chasing it. This is just a recipe for inflation, while not so much unemployment, since demand was actually “too high”. At the same time, it’s undeniable that inflation would have gone up even without excess demand, since there was less supply - which is why Europe, which had a smaller stimulus than the US and a more conservative Central Bank, also has lower inflation. Ironically enough, the less aggressive the stimulus, and the less acomodative the monetary policy, the bigger role for supply chain issues in inflation.

Thanks, Brandon

In early 2021, the US Congress pass Biden’s “American Recovery Plan” (ARP or “the stimulus (package)” from now on), a 1.9 trillion dollar relief plan that included extending jacked up UI benefits, giving nearly everyone a 600 dollar check (on top of 1400 before), roughly 160 million dollars in healthcare investments, 325 million in various investments, and 500 million in state and local aid. There were about 800 million in direct “handouts” to people, according to some estimates. The claim that “the stimulus caused inflation” is both technically correct and technically incorrect.

Now, let’s start with the basics: why was there even a stimulus in March 2021? Besides from “Joe Biden wanted to be popular”, the obvious answer is that it wasn’t crystal clear the pandemic was over. Most people weren’t vaccinated, new variants were seen as a really serious threat, and people didn’t know whether there’d be another big wave that kept people at home (or forced them, if restrictions were imposed) and hurt businesses and employment. Many economists, therefore, defended it as an insurance of sorts - there were huge potential downside risks for a “COVID is over” approach back then, so this was a reasonable risk to take (in my humble opinion).

So, first, people had a lot more money because the government gave them a bunch of money. But people also had more money because they had spent less: COVID meant that you couldn’t go out for dinner, get a haircut, go on vacation, etc. This entailed that all the spending would, at least initially, get concentrated on stuff that people could still get - namely, durable goods. So because the supply shocks were real, even at-potential NGDP would have resulted in more inflation simply because potential real output was temporarily lower; but this meant above trend NGDP, due to excess savings from both fiscal policy and a previous change in expenditure composition.

A stimulating debate

The big claim about stimulus isn’t just that excessive demand and depressed supply would have, in a vacuum, raised prices - there’s also the fact that demand begets demand. If you get a hundred dollars and spend them at the store, the store has a hundred more dollars - so it, for example, pays its employees more, who spend more, and so on and so forth. This is what’s called the fiscal multiplier. Most of the people ringing the alarm about the stimulus focused on two claims: the stimulus was much larger than the output gap (difference between actual and potential GDP) and the multiplier effect would have made it worse.

The exact size of the fiscal multiplier is a really contentious debate, with basically three positions: New Keynesian economists think it’s generally at least 1 (so one dollar of stimulus = one dollar), Monetarist economists think its 0 because monetary policy cancels out the extra demand, and New Classical economists think it’s less than one because people just save their stimulus to pay for the future tax hike (called Ricardian Equivalence). Now, the problem is, save the New Classicals because Ricardian Equivalence is dumb and fake, they mean different things when they say multiplier: the NKs use it as “the effect of government spending in output”, while the Ms use it as “the effect of government spending in spending”. So when Scott Sumner says that the multiplier is roughly zero, what he means is that monetary policy will simply tighten to not let inflation rise, and therefore it won’t actually increase spending. Meanwhile, when the empirical data shows that government investment actually does grow the economy, what it means is that the government building a bunch of bridges and stuff makes the economy more productive. But that’s a really different claim than what Sumner is making!

So who is right about the stimulus? The stimulus wasn’t really an investment, so it mostly goes into the Monetarist world. The problem here is very simple: the Fed didn’t offset the big fiscal stimulus, proving Sumner & co right and wrong. Why the Fed didn’t offset the stimulus at any point during 2021 is a whole can of worms, but needless to say they didn’t, and didn’t notice until it was way too late. This doesn’t mean that the Fed “printed too much money”3, but actually does mean that the Fed didn’t “take away the punchbowl”, which is what everyone complained Ben Bernanke wasn’t doing during the much slower recovery from the Great Recession.

Let me play among the stars

What relationship does the labor market bear to inflation? The normal relationship used here is the Phillips Curve: a negative tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. Basically, why is there a negative relationship? There’s two stories here, both starting from too much demand:

Lower unemployment means higher wage growth, which means inflation

Higher inflation means lower real wages, which means lower unemployment

Is the Phillips Curve relationship real? In the past, I’ve said (kind of) no. But I’ve actually somewhat changed my mind: it’s real, but useless. Of the two explanations above, the first one is normally called the “price wage spiral” when it happens for long enough, and I think it doesn’t make a lot of sense - real wages normally go down, not up, when inflation accelerates, and this doesn’t really happen unless you have a labor market extremely stacked in favor of employees, or if inflation expectations are just off the hook (meaning people don’t know what to expect so they ask for unreasonable amounts, and then prices follow). And it also kind of implies that more demand can always and everywhere raise employment, and that real wages rise during the process, at least initially. The latter is clearly a better fit for the US, at least currently: employment and unemployment recovered, the labor supply shrank because of retirements and lower immigration, and then kept going because wages rose, but less than inflation (i.e. fell, in terms of how much you can buy), at least after early 2021, when everyone anticipated less demand and had to hurry to hire more.

The story here is simple: real wages first increase because, in many sectors (such as food services and retail) the recovery was much faster than anticipated. Then, because there’s too much money chasing too few things, inflation ticks up - and wages only kind of follow, because the US has very well anchored inflation expectations (since the Volcker Shock, at least), a really low unionization rate and a lot of employer-side market power4. Since inflation grows faster than wages, labor becomes cheaper, and thus employers hire more. The negative trade-off is thus born.

But here’s the catch: the negative trade-off only exists under suboptimal monetary policy. If monetary policy is optimal, then there’s never any excess demand, there’s never any excess inflation, and there’s never excessively low unemployment - ergo, the Phillips Curve flattens out simply because things are going well. A correlation of any kind between inflation and unemployment means that the Fed is not doing enough to keep the economy stable. This is absent supply-shocks, which is fairly reasonable to assume since they happen not very often and it’s not like the Federal Reserve can just print more oil like it can money. If monetary policy is always optimal, that means only supply shocks it can’t, and probably shouldn’t, do anything about change the relationship between inflation and unemployment. Because supply shocks raise both, then under optimal monetary policy and a supply shock, the Phillips curve has a positive slope.

Conclusions

What can we take away from this? Something from each section:

Inflation is always and everywhere too much money chasing too few stuff. The total amount of nominal spending in the economy determines how high inflation goes, and this can be measured by Nominal GDP better than CPI.

Too much money doesn’t preclude too few stuff. The 2021 stimulus might have been excessive, but it also was coupled with supply shocks that reduced the total amount of things available. Ergo, even on-trend demand would have resulted in inflation, and above-trend demand just made it worse.

The stimulus was only too big because the Fed didn’t do enough. Biden’s stimulus was so big, besides politics, because of uncertainty about how bad COVID would be. This was reasonable. What wasn’t reasonable was the Fed not noticing inflation was getting out of hand and not offsetting it.

The labor market isn’t driving inflation. Wage-price spirals aren’t really possible in the present US given anchored expectations and labor market institutions. The Phillips Curve only exists because of bad monetary policy.

Stay tuned for next week so I can talk about what the Fed did and didn’t do, why “more stuff” isn’t really a satisfactory solution, and why a second Volcker Shock isn’t necessary to tame inflation.

Sources

The basics

David Beckworth, “The Stance of Monetary Policy: The NGDP Gap”, Mercatus Center, 2020 (and their figures for the NGDP Gap)

Dylan Matthews, “How I (and US policymakers) got inflation wrong”, Vox, 2022

Matt Yglesias, “The Fed should do more to fight inflation”, Slow Boring, 2022

Matt Yglesias, “Why we got more inflation than I expected”, Slow Boring, 2021

The supply chain and supply shocks

This thread by Jason Furman about US-Europe comparisons

Peterson Institute, “For inflation relief, the United States should look to trade liberalization”, and “China's recent trade moves create outsize problems for everyone else”, 2022

The stimulus

Olivier Blanchard, “In defense of concerns over the $1.9 trillion relief plan”, PIIE, 2021

CFSPB, “How Much Would the American Rescue Plan Overshoot the Output Gap?”, 2021

Scott Sumner, “Why the Fiscal Multiplier is Roughly Zero”, Mercatus, 2013

Jason Harrison, “It's Not Roughly Zero” and “The Conceptual Issue with the Fiscal Multiplier: An NK and MM Perspective”, both Nominal Thoughts, both 2021

The labor market

Niskanen Center, “Managing the macroeconomy isn’t “closest without going over” and “Is the Phillips Curve Back? When Should We Start to Worry About Inflation?”

McLeay & Tenreyro (2019), “Optimal Inflation and the Identification of the Phillips Curve” (summarized version on VoxEU here)

The main evidence for this argument, FRED charts, is actually mistaken - there was a weird methodological change in M1 that was reflected in M2 and M3, resulting in 100% completely artificial increases because they didn’t make the same correction for older data (for some ungodly reason)

Jeremy Rudd’s paper, which I don’t like or agree with, actually got this spot on: a wage price spiral isn’t possible because of such institutional arrangements. He does discount expectations, but his whole point was that they’re fake anyways.

You wrote "million" instead of "billion" in the ARP breakdown paragraph.

A good piece but I think one item you did not cover was demand shocks, specifically:

"I’m gonna come back to this in a bit, but the US had a highly stimulative policy, spending on services collapsed because of COVID, and issues in Asia, plus uniquely American regulatory issues (tariffs, port zoning and automation, stuff like whatever the hell the Foreign Dredge Act is) meant that there suddenly was a lot less stuff to go around and a lot more money chasing it."

Well except not really. At least when everyone was at home there was a lot of stimulus but there wasn't a lot of spending. You could buy Netflix and get take out but during shutdown, you really couldn't spend much of your money.

And I think this is something a bit new. Monetary theory has dealt with supply side problems before. They could be a shock like an oil embargo in the 70's or they could be an economy that just isn't very dynamic because of super strong unions, regulations or gov't controlling major enterprises (think how the UK once owned the coal mines). But not really demand shocks. It's kind of assumed people will spend based on their income and you can whack down spending by a surge of unemployment but if people have money, they will spend it.

But model what happens if they don't spend it. Let's say producers supply 100 units every month and that is what is demanded. All is well except when pandemic hits, demand drops to 50 units each month. Now there is some supply side shock too, with people staying at home and all perhaps the company can only make 75 units, but that doesn't matter since demand is 50. If the producer happened to have had some safety inventory on the side, the problem is even worse.

Too many goods chasing too few dollars = deflation.

A Central Bank trying to follow a monetary policy would suddenly find the need to print money and print it fast!

After a while, people start thinking the pandemic has ended. Demand starts to slowly increase. The producer assumes it will go back to 100 but when? If demand increases, say, 10 units a month, it will take 5 months to get back to 100. That's fine, but what if they are wrong?

Say we get a 20 unit increase from 50 to 70. Since production was only planned for 60 units, there is a 10 unit shortfall. The producer could let there be a shortage of 10 units, or perhaps they could drastically raise prices to force demand down to 60.

Say the next month demand was supposed to have arrived at 70, but now the producer is scrambling, having assumed demand is now increasing by 20 units per month, they fear they need to make 80 units. There is a scramble to bring workers back sooner and while last month they may have let the shelves go empty, this month they try to get ahead by doing that price increase.

The pandemic was not a clean shutdown where everything stopped until the virus was gone. It was a shutdown with a re-opening, then a closure, then another re-opening and then geographical detachment as some places increased activity while others pulled back and then reversed as caseloads surged in one part of the country then moved to other parts.

The central bank here has a much more difficult problem. If they don't allow inflation, signals to the producers do not get through. Since demand is returning, you could get a whipshaw effect. One month producers raise prices expecting too much demand but then if demand falls, they may find prices have to drop. In my example I used a simple '100 units' but there's thousands of products. For example, lumber has already had several booms and busts in prices (remember it was surging back in 2021?). Not only do we have many demands for different things returning to 'normal', normal is now different with things like demand for office space less because quite a few workers suddenly have started working from home almost all the time now. Recreational air travel has increased but business air travel has remained low.

Long story short the snowglobe of the world has been shaken pretty badly and in the short run it's going to be a lot of little snowflakes milling around before they settle.