Three factoids that aren't quite right

Homelessness, climate change, and inequality are important issues. Not anything goes when talking about them.

“There are 31 vacant houses for every homeless person”

A frequently cited fact to rally against the need to build more houses in order to increase housing affordability is that there are actually enough houses for everyone, it’s just that many of them are held vacant.

Well, according to the US census, there are about 17 million vacant houses in the United States, and roughly 600,000 homeless people. The math turns out to around 28 housing units for every homeless person, which isn’t exactly 31 but the number of homeless people seems to be frequently understated, by about 20%.

Does that mean that there’s 17 million houses just sitting around? Not actually. The largest group are 6 million and change “other vacant houses”, which are frequently abandoned and in need of major repairs, or belong to deceased people and are being adjudicated by the court system. The second group, some 5 million and three quarters, are seasonally empty houses - vacation homes, second homes, or other such properties. Then there’s another similarly large group of properties that are on the market looking for a buyer/renter, or homes that have already been allotted to someone but who hasn’t moved in yet. So of the three groups, only the vacation homes seem to be really available for the taking, considering that nobody would want to move to a decrepit, decaying house in a second-tier city, plagued by crime and poverty.

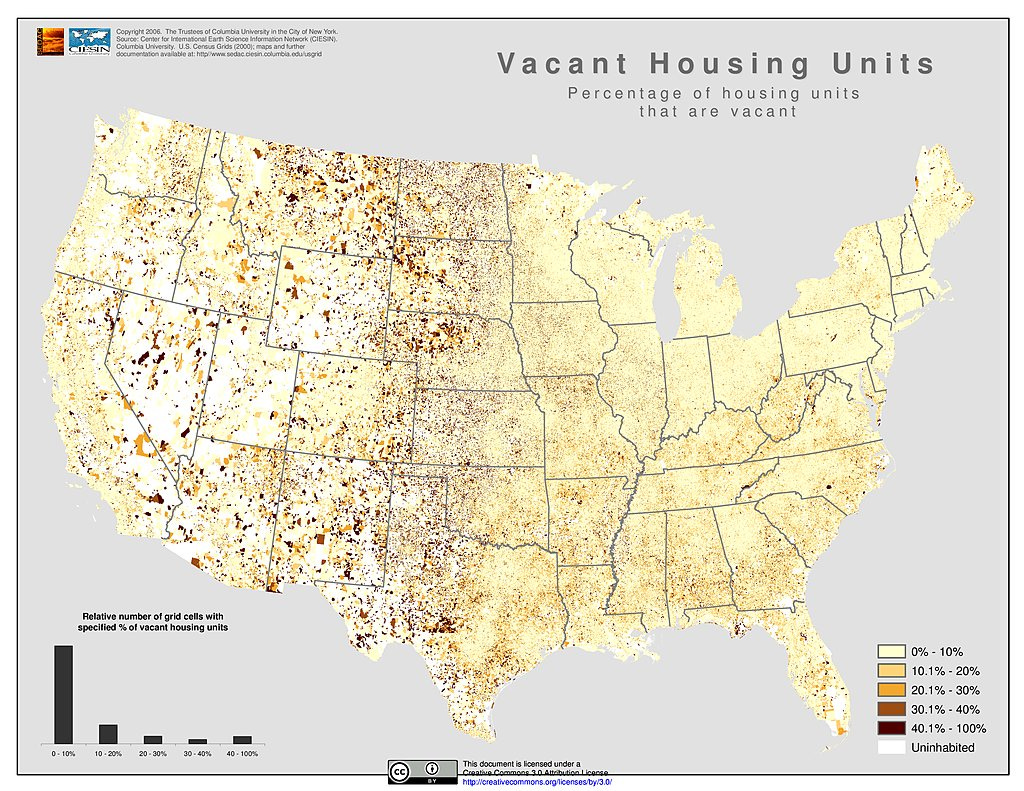

So, why shouldn’t rich people hand over their vacation homes to house the homeless? Not much of a reason except that they’re not located in the same places. Homelessness tends to be closely linked to poverty and/or to high cost of living - the more expensive housing is, the likelier it is people, particularly low income people, are homeless. Most homeless people live in large urban areas like New York City, Los Angeles, Seattle, or the Bay Area, or in very poor areas like Humboldt County, California; Imperial City, California. Washington DC, with the highest rate of homelessness in the US, has just 1.4% of its housing devoted to seasonal homes (primarily, it appears, of the politicians who live there). In contrast, Ocean City Maryland, a resort town, has 87% of its vacant homes be second homes.

But the main reason why housing homeless people in empty second homes wouldn’t work is, simply, that most of those homes aren’t in the same places as homeless people. Most housing units for this purpose are in places like the Mountain West, rural New England, or the Great Lakes - not precisely San Francisco and Seattle. New England, with the highest concentration of vacation houses in the US, has the lowest vacancy rate and a not especially high homelessness rate.

Empty houses not being in nearly the same place as the people who don’t have a house is actually a massive problem, especially when some cities have too much housing (generally declining Midwestern cities like Detroit or St Louis), and some have far too little (most infamously, California). This big mismatch at the heart of housing policy is why this paradox of abundant houses but endemic homelessness can happen - they’re not in the same place.

“100 corporations are responsible for 70% of emissions”

This claim is actually true, but it doesn’t mean what it’s commonly cited to mean. Normally, the point this statistic is that some combination of capitalism, neoliberalism, or whatever is responsible for climate change, not “ordinary” people and their decisions. Originally, it comes from a 2017 The Guardian article of the same title about a report from the same year that explores the role a hundred companies had on global carbon emissions.

However, neither the report or The Guardian meant the normal interpretation of that fact. The report was explicitly about fossil fuel producers, and the article reported about that as well. Worth noting is that about 59% of those emissions are from state-owned companies, 32% from public companies with singificant private ownership, and just 9% from private investor-owned companies, so this doesn’t say much about the wider “system” - socialist China has been building coal plants at a breakneck pace, and the Chinese coal industry was the single largest CO2 emissor between 1988 and 2015.

When the report says “the fossil fuel industry accounted for 70% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions”, it refers to the 70% of GHGs that are related to energy use - the largest source of emissions globally. These companies didn’t just put out millions and millions of tons of carbon dioxide for no reason - but rather, for the explicit reason that people and other companies were purchasing their products.

Now, casting individual blame on each person for the makeup of their country’s energy sources is ridiculous, but it’s equally ridiculous to just pretend greenhouse gas emissions are caused by pure corporate greed (not that the global fossil fuel industry hasn’t had its fair share of tobacco-tier scientific dishonesty).

In the end, it’s all about energy - everything in the economy uses it, and the dirtier it is the more problematic climate change becomes. In fact, the whole point of the report this fact comes from is to make clear how the decoupling between economic growth and CO2 emissions might work.

“Productivity and wages haven’t caught up”

The main claim here, which is primarily embodied by the graph above, is that labor productivity has grown significantly since the 1970s, but wages have not grown as much (actually, that they’ve barely grown). Former CEA chair Jason Furman made an adjacent point in a Peterson Instititue piece recently, looking at income growth for typical American families.

The most famous “debunking” of the claim above is this one by Veronique de Rugy at the Mercatus Center. The graph isn’t particularly difficult to interpret: of the 70-point gap between productivity growth and average hourly wages, about 12% is caused by not including the earnings of self-employed workers, 39% is caused by choosing CPI inflation versus other measures of inflation (CPI tends to overstate it, and the difference with other indeces becomes especially pronounced after the 80s), and 42% by choosing average wages instead of average compensation.

The most significant part of this story is compensation versus wages - basically, compensation includes non-wage benefits like healthcare and childcare. Since healthcare and childcare have been getting more and more expensive since the 70s, then the growing maw of supply-side constraints is swallowing American prosperity whole. Put another way, if companies paid for people’s rents, then housing getting similarly expensive over time would have swolen up to make up a significant

There’s also some confusion between productivity, which is an average, and wages, which are usually median wages - since there’s significant inequality in labor income, the median wage is lower than the average way. Plus, exactly how you measure productivity and how you select which workers to compare with average productivity. The EPI graph at the beginning is actually of a subset, nonsupervisory and production employees - so it could be that their productivity has just grown more slowly than that of the average worker. Economist Michael Strain has also written up this topic pretty thoughtfully, and making the same broad points: inflation adjustments, measurement of productivity, and compensation versus wages make different claims be all correct at the same time.

Obviously enormous caveats have to be made - for example, that non-wage compensation is lower for lower income workers, or that using averages distorts how representative each measurement is, or that more granular productivity data for each subset of employees doesn’t really exist. Perhaps there isn’t a disconnect at the top of the earnings distribution, but there is at the bottom, where employers exert significant power over their hires - some estimates show that there might be a wage-productivity gap of up to 17% because of monopsony power in labor markets

Regardless, “wage decoupling” (or delinkage) is an issue across developed nations to any given extents. An interesting paper in this literature is Summers and Stansbury (2018), which defines two hypothesis: strong delinkage, which posits the popular claim of wages barely growing and productivity soaring, and strong linkage, which assumes the opposite - that wages are actually tracking productivity.

Looking at roughly the same data and carefully examining each possible assertion (average compensation versus productivity, median compensation versus productivity, “lower skilled” compensation versus productivity) the conclusion drawn is that there is a reasonably strong linkage between properly measured compensation and both median and average compensation, while there is a much weaker, but still present one, between production/nonsupervisory compensation and productivity. From the paper itself:

Our regressions are supportive of substantial linkage between productivity and all three measures of compensation: median, production/nonsupervisory and average. Over 1973-2016, a one percentage point increase in the rate of productivity growth has been associated with an increase in compensation growth of 0.7 to 1 percentage points for median and average compensation, and of 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points for production/nonsupervisory compensation. Almost all specifications strongly reject the “strong delinkage” hypothesis, and the “strong linkage” hypothesis of a one-for-one relationship cannot be rejected for either median or average compensation (while it is rejected for production/nonsupervisory compensation). Evidence on different deciles of the wage distribution also shows large and significant positive co-movement between productivity and wages at the middle deciles. [Emphasis mine]

So the claim is generally correct, wages haven’t tracked productivity one to one, but it generally depends on how you define each variable - the most annoying and pedantic kind of disagreement, where everyone can define each word in a way that proves them right. All in all, there has been both a significant underperformance of the US in terms of personal income and a significant increase in inequality - but both can be shown in different, more effective ways!.

>The second group, some 5 million and three quarters, are seasonally empty houses - vacation homes, second homes, or other such properties.

That's the point. Fix homelessness, then we can start worrying about giving rich people second and third houses that are empty most of the year.

You seem to not comprehend that people moving into places are also leaving an empty place behind. It's not that hard to figure out. People don't need a home to themselves as well, which significantly decreases the number of residencies that you would need to get the homeless off the streets. You also state: "nobody would want to move to a decrepit, decaying house in a second-tier city, plagued by crime and poverty.", but I would argue any house in those places would be preferential to living on the street in those places. Not to mention that repairing a house is generally cheaper than building completely new ones. Doing nothing and acting like there is nothing you can do is not a solution.