The Ends of Four Big Migrations

Does immigration lower wages? No. Does it cause unemployment? Also no.

The Mariel Boatlift

In 1980, roughly 125,000 Cuban migrants arrived on Miami, representing a 7% increase in the city’s labor supply, and a fifth of all Cuban workers. 1980s Miami had large proportions of foreign-born and minority workers, and slightly below average education levels (lower for non-whites and immigrants).

Originally, this phenomenon was studied by economist David Card in a famous 1990 paper. The common sense conclusion is that such a big increase would have had “bad” effects on at least Hispanic workers, because increased competition for jobs would have increased unemployment and/or reduced real wages. A cursory look at the actual results would seem to coincide with that: real wages for all Cubans decreased 6-7% in 1980 to 1981, while unemployment increased from 7% to 10%.

However, this misses a key issue: the Mariels made up a fifth of all Cubans, and when they arrived, they received wages that were about a third lower than those of other Cubans, and had unemployment rates that could reach as much as 20%. Simply put, the effect on Cuban employment wasn’t caused by “more competition”, but rather by a change in the composition of the Cuban labor share. Let’s use some simple math: imagine a labor market of 100 people, 5 of which are unemployed. If 20 people immigrate and none of them find jobs, the unemployment rate would increase from 5% to 20%… despite no jobs being lost! Thus, there was basically no effect on the wages or employment of non-Cuban natives, and a small effect on the wages or employment of Cubans - mostly due to counting the new immigrants as Cubans.

Another explanation can be found in Bodvarsson, Van der Berg, and Lewer (2008): since immigrants don’t bring their own food, clothes, or homes with them to their new home countries, they also have an effect on labor demand - businesses may hire most of them anyways without lowering wages, because they actually buy goods and services in the economies they move to.

Then came the controversy. A 2015 paper by George Borjas argued that previous papers missed the point, because you couldn’t compare the Mariels to everyone else: you had to compare them to people with their same skill levels. Adjusting for education, gender, and race, a clear pattern emerges: wages for high school dropouts (60% of the Mariel Boatlift immigrants didn’t finish their degrees) decreased up to 30% in the Miami labor market.

A 2015 study by Peri and Yasenov replied to Borjas: his results were highly spurious, and mostly were caused by using very specific data points and adjusting the sample so much that some groups were reduced to less than 20 observations, with margins of error to the tune of 20% to 30%. Borjas responded in 2016, with a criticism of the Peri and Yasenov methodology, since their adjustments to his adjusted data added too many workers that didn’t compete directly with the new immigrants (most notably, counting high schoolers as high school dropouts).

Clemens and Hunt (2017) provide an alternative explanation: the racial composition of the sample used by all previous studies changed significantly right after the Boatlift, and this gave the “findings” of Borjas a leg to stand on. Borjas and Clemens went back and forth a bit on methodology, but in the end the findings of Card (1990) were maintained: there wasn’t a significant shock to labor supply in 1980s Miami (besides more general macro trends for the US economy), and there may have even been a positive shock to labor demand.

The European refugee “crisis”

Due to the (somewhat ongoing) Syrian civil war, 1.2 million people requested asylum in the European Union in 2015 alone, plus another 800 thousand or so in 2014. This was the largest influx of people into the continent in decades, larger than the displacements caused by the Balkan Wars of the late 90s or the fall of the Soviet Union. Their distribution across the continent was uneven, with nearly a third moving to Germany alone.

The first issue is that refugees normally don’t move to countries for economic reasons - but rather, to ensure their personal safety in the first place. Additionally, refugees had roughly education than natives in general, even though it highly varies by country of origin and specific professions - for example, a large percentage of Syrians specifically had medical training. Furthermore, refugees don’t necessarily speak the language of the countries they move into, which is far more common for “normal” immigrants. And refugees were normally much younger than the aging European natives, so there wasn’t much of a risk of them not being able to work at all.

Both of these factors show that there isn’t much direct competition between natives and refugees - they simply don’t have enough skills to meaningfully impact their labor market outcomes. Plus, the effects can mostly be beneficial, through the labor demand channel mentioned above. Both of these must be conditioned to include that the labor market outcomes of migrants are very dependent on which countries they move into: countries in recessions have worse outcomes than countries with booming labor markets.

The main remaining concern, in consequence, is whether or not refugees can be “too costly” in fiscal terms for their host countries. Initially, yes, but with a big caveat: if migrants can get integrated into the labor market, their outcomes improve significantly, and they “pay for themselves” through effects on aggregate demand, plus their own tax payments. Plus, younger and more educated migrants tend to have higher (net) contributions to fiscal accounts through their lifetime.

So the main concern remaining is about the migrants themselves: do they actually manage to be properly integrated into the economy? All groups of migrants, be they economic immigrants or refugees, tend to start with much lower wages than native and catch up overtime. This is even true for migrants who are as educated as natives and are proficient in the language (not a given) .

However, there is a significant gap between “normal immigrants” and refugees too - refugees are 22% likelier to be unemployed and make wages that are 20% lower as well. This gap persists even after adjusting for language proficiency and skills. In fact, 60% to 80% of this gap can’t actually be explained by any qualities of the migrants themselves - simply put, refugees make less money by being refugees and not economic migrants.

There’s a number of potential explanations: first, that refugees tend to have gone through traumatic experiences, which harms their ability to perform adequately in the labor market (who would have thought). Secondly, that refugees frequently move to countries that aren’t rich or have high unemployment rates already. Thirdly, many countries actually ban refugees from applying for jobs or receiving training until their applications are fully processed - which considerably harms their outcomes. And many European countries adopted so called “ethnic dispersal” policies to prevent too many refugees from settling in the same area. This could have two different effects: if refugee enclaves are poorer and have less opportunities, this would facilitate integration. But, on the contrary, many labor market oppportunities rely on personal connections and community networks - say, a refugee recommending their neighbor for a job in the same company as them. For the countries that adopted these policies (Sweden, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway, the UK) the latter effect normally prevailed, and this hurt refugees’ chances of integration.

The Soviet Migration to Israel

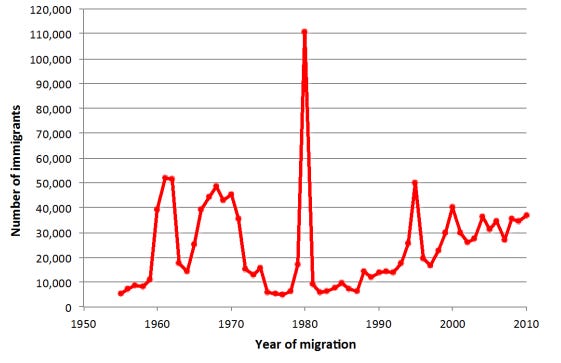

In 1989, the Soviet Union lifted emigration restrictions for Jews to move to Israel, and by 1990 it had been dissolved altogether. As a result, some 700,000 Jews from the former Soviet Union moved to Israel during the early 90s- and 330 thousand in 1990 and 1991 alone. Between 1990 and 1994, the country’s population increased by 12% and its working-age population by 15% - the largest shock by far in all destinations common for Soviet emigrants. It would appear reasonable to think that Russian immigrants to Israel didn’t move there for economic reasons, but rather because it was a simple option. Let us also consider that Israel only had half of US GDP per capita in 1989, versus two thirds now - a decently well off country, but not a rich one by most measures.

The Russian immigrants were one year older, on average, than native Israelis, and had higher levels of education, with one additional year of schooling (13 years vs 14 years) and much higher attainment of higher degrees (40% to 60% vs just 30% of native Israelis). Also interesting is that Israel is a small country (basically a single labor market) receiving a massive amount of highly skilled migrants in a short period - quite unusual circumstances.

Initially, you would expect Russian immigrants to compete with highly skilled Israelis in their professions, lowering the wage premium for their skills. Additionally, you could also observe a decrease in real wages that lasted until 1997, and higher unemployment until 1995. But there’s a catch: the relative wages of Israelis compared to Russians didn’t change much, and neither did their employment outcomes.

Starting with employment, there was barely any relationship between unemployment for Israelis and presence of Russians in their industry, pointing to other factors raising unemployment and yet another composition effect: Russians getting counted as unemployed raised the unemployment rate.

As for wages, besides the differential between natives and Russian immigrants (that points to composition effects), there is also a difference between average wages for both groups adjusting for presence of Russians in the occupation in Israel or in Russia: the former has negative effects, the latter barely has any. But occupation of Russians in Russia is stronger for learning what they actually did, and this points to a potential explanation: the Russians worked in professions that didn’t utilize their skills properly, so their average wages (and those of all Israelis, considering they made up 15% of the labor market) went down. An example of this is that, among doctors, Russians tended to take lower paying positions, while native Israelis received promotions.

The Venezuelan exodus

Since 2013, living standards in Venezuela have slowly deteriorated, with hyperinflation, mass poverty, and political violence becoming common. As a result, some 4.3 million people left the country for its neighbours - mostly Colombia (about half of them), Peru (about a quarter), and Ecuador and Chile (about a tenth each). Unlike in prior cases, Venezuelan migrants are somewhat more educated as other workers their host countries, speak the same language, and come from basically identical cultures - plus, unlike Europe or the US, Latin America tends to have a large informal sector that can employ migrants even if their legal status is uncertain.

From 2013 until 2018, Venezuelan migrants mostly worked in the informal sector, earning lower wages than average Colombians. Informal workers earn lower wages, work fewer hours, and have worse conditions across Latin America - and their hiring and firing process is extremely flexible. As previously stated, the state of the economy is highly important to the effects of migrations on labor market outcomes. Unfortunately, the regions of Colombia that migrants typically lived in (the ones boordering Venezuela) weren’t especially strong. Most studies tend to find somewhat large effects on wages, ranging from 6% to 11% using updated versions of Card’s methodology. However, in neighboring Ecuador (similar enough to both Colombia and Venezuela), there was a much smaller effect on native wages. In both countries, younger, poorer, less educated workers have been most impacted, due to their heightened competition for employment in already weak labor markets.

Additionally, in 2018 the Colombian government decided to grant amnesty and work permits to nearly half a million Venezuelans through the Permiso Especial de Permanencia. As a result, even if a large proportion of migrants didn’t choose to apply, due to either not knowing the advantages of potentially accessing a registered job, knowing them and preferring informal employment, or having dificulties actually accessing a registered hob, the number was such that their impact on formal employment in Colombia can be examined.

Granting work permits to undocumented migrants at that scale has not had a statistically significant impact on wages, and has only reduced employment by a paltry 0.15%. Two explanations are possible. The first is that only a limited number of firms may hire Venezuelans in the first place, reducing competition with natives. Secondly, the fact that many Venezuelans didn’t apply for a work permit, but still continued working, probably points to some degree of a demand-side impact on firms.

Conclusions

In the broader literature, there isn’t an established link between inflows of migrants and significantly worse labor market outcomes for natives. Looking at these four particular episodes, we can derive some similarities.

Firstly, there isn’t really a lot of competition between migrants and natives. Natives have connections and local references, and most importantly a very relevant skill that migrants might not: the local language. As a result, migrants tend to work jobs they are overqualified for. This skill barrier is generally reduced over time - but it takes a lot of it, as much as 15 or 20 years in some cases. And furthermore, it’s very common for migrants with university degrees to not have their qualifications recognized by host country companies at all, worsening the skill utilization issue.

Secondly, restrictions on work permits tend to be a big deal. In countries without informal sectors, migrants may be unemployed for long periods of time, which leads to worse labor market outcomes in general. This means that taking long times to process requests of people already in the country harms them significantly.

Thirdly, you can’t just look at labor supply and you can’t just look at the labor market. Immigrants tend to buy things, rent homes, and even start their own businesses. As a result, competition for jobs might not be more intense - it may even be less so, because the market got bigger and firms hire more workers.

Sources:

“The Mariel Boatlift Controversy” (2017), Sylvia Merler, Bruegel

Card (1990), “The Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market”

Borjas (2015), “The Wage Impact of the Marielitos: A Reappraisal”

Borjas (2016), “The Wage Impact of the Marielitos: Additional Evidence”

Clemens & Hunt (2017) “The Labor Market Effects of Refugee Waves: Reconciling Conflicting Result”

IMF (2016) “The Refugee Surge in Europe: Economic Challenges”

“Israel’s immigration: A unique assimilation story with a message” (2018), Assaf Razin, VoxEU

Cohen & Tsieh (2000) “Macroeconomic and Labor Market Impact of Russian Immigration in Israel”

Friedberg (2001) “The Impact of Mass Migration on the Israeli Labor Market”

Santamaria (2019) “Venezuelan exodus: the effect of mass migration on labor market outcomes”