Given recent geopolitical tensions, prices for commodities have risen to levels last seen a decade ago: wheat, soybeans, oil, gas, metals, you name it. The obvious question on everyone’s mind is “is this good or bad for the economy”. As usual, it depends, although it wouldn’t be much of an article without mentioning on what.

The way to understand the economic impact of a sudden, exogenous increase in global commodity prices (“exogenous” becuase it seems unlikely that any country’s monetary and/or fiscal policy caused Russia to invade Ukraine) is as a supply shock, and one of prices. The prices that actually are increasing are, in broad categories, minerals and metals, fuels, and “food” (soybeans, wheat, corn, etc). We’ll be focusing mainly on the last two, since minerals and metals aren’t that salient basically anywhere.

There’s three main channels on which a sudden lurch in commodity prices impacts national economies: prices, output, and the balance of payments. Put in simpler terms: “does it cause inflation?”, “does it cause a recession?”, and/or “does it increase the trade deficit"?”. Roughly speaking, there’s a first wave of impacts caused by the change in prices directly, and then further waves which are caused by the interaction of those effects, plus the policy response to them.

Boom and bust

“Do prices going up make prices go up?” seems like a painfully stupid question, with a painfully obvious answer: it does.

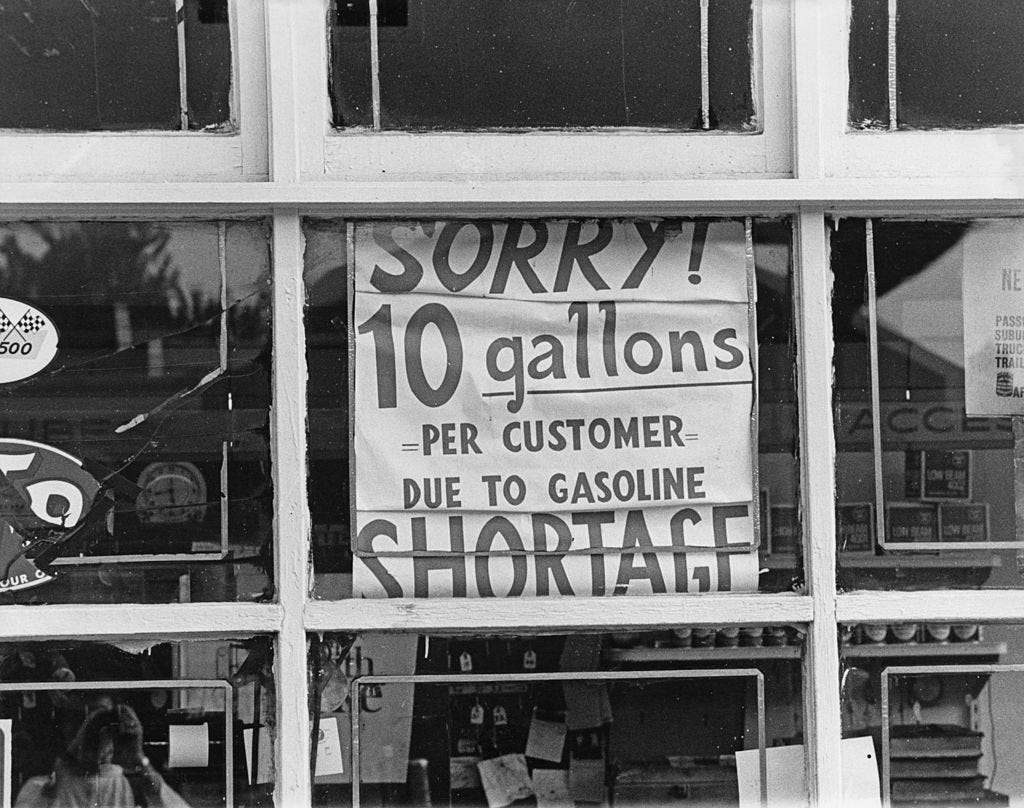

On first glance, commodity price hikes do make inflation go up - especially if those commodities are things people actually buy, such as wheat or fuel. This effect obviously impacts net importers of commodities negatively, but it also impacts net exporters as well. The reasoning is fairly straightforward: an exporter (say, of wheat) has to choose between selling at the domestic price or at a higher, international price. In order for any sellers to sell domestically, prices have to increase to a level that makes selling locally profitable.

The obvious counter to the “prices going up is inflationary” logic is that there is no change in price growth, only a one-time jump in the price level of certain goods; once all products adjust, the inflationary “bump” will be over. Of course, not all prices adjust automatically, so it might be a somewhat prolonged bump, but the distinction between a higher price level and higher price growth remains.

But evaluing the inflationary impacts of complicated when adding the fact that expenditures on food and fuel are fairly inelastic. Something that might be evident to many readers is that families operate on a fixed budget - that is, they only have so much money to spend. Under a fixed amount of expenditures, an increase in the price of one item can be compensated only by a decrease in the quantity consumed or by a decrease in spending on some other item. If we consider that quantities spent on food and fuel are not very liable to be reduced (i.e. there is little substitution), then the logical conclusion is that higher commodity prices are offset by lower consumer spending on other goods.

But since wheat, oil, minerals, etc are directly involved in production (as inputs, for instance) then an increase in their price raises production costs, which reduces real supply. This means that a supply side shock can, and often does, reduce the total amount of output in an economy. Of course, it could also increase the produced amounts of the commodities, as companies maximize profits, but if the market isn't perfectly competitive then they don’t have much of an incentive - in the medium run, equilibrium prices would be lower if they increased quantities.

Considering that inflation can generally be attributed to “too much money chasing too few goods” (which causes which is a matter of debate), then an increase in the prices of commodities can reduce aggregate demand (i.e. reduce the amount of money) but also aggregate supply (i.e. reduce the amount of goods). Exactly which effect dominates depends on a variety of factors, so it can either be doubly recessionary (lower supply AND lower demand due to substitution), inflationary (just higher prices), or both at the same time - the same overall level of demand plus lower aggregate supply.

This also points to why the monetary policy response to the issue is so difficult: should central banks focus on the additional unemployment caused by the supply-side recession, or by the additional inflation? It’s not particularly clear which one. In a vacuum, most would agree that temporarily higher inflation is acceptable if it preserves output. However, given that inflation in most countries is at a multi-decade high, perhaps policymakers might want to reconsider and prevent it from spiraling upwards even further.

Imbalance of payments

Now, for a paragraph US readers can skip entirely: what’s the effect on the balance of payments? And what are its implications for macroeconomic policy? I’ve done a post on Russia’s balance of payments a while ago, but let’s recap.

The flow of foreign currency going in and out of a country is called the balance of payments. It has three main components: the current account, capital account, and financial account. The current account has three big parts - the trade balance (exports of goods minus imports of goods), the services balance (exports minus imports, but of services), and the “rents” balance: net wages paid into the economy (say, by and from multinational companies), interest payments, corporate profits, and remittances. The capital account is mostly changes in debt from debt forgiveness and weird stuff like patents, intellectual property, and football player transfers. The financial account includes both foreign direct investment (think, a company buying another company or opening a factory) and portfolio flows (“speculative” investment, aka buying stocks and bonds). When the balance of payments is negative, that means dollars are “leaving the country”, and when it’s positive, they’re “entering” (or balanced when outflows compensate inflows). The balance of payments is reflected on the country’s international reserves, basically a Scrooge McDuck pile of USD a country keeps. The impact on reserves depends on the exchange rate regime.

Exchange rates are the value of a currency measured in another - normally, US dollars. For example, Argentina’s black market exchange rate was 206 pesos, meaning you need 206 pesos to buy a dollar (or can exchange one for slightly less, 202 pesos). That is the nominal exchange rate, because it doesn’t adjust for prices. For example, if the dollar increases 10% in a year but inflation is 15%, then that means the country is getting more expensive for foreigners. The inflation-adjusted exchange rate is the real exchange rate.

Commodity prices only really affect the current account (especially “goods”) but the rest is heavily reliant on both the exchange rate and interest rates, both of which are liable to be influenced by the effects detailed in both the previous and the current section. More expensive commodities can result in higher imports and/or higher exports depending on which products a country specializes in.

Countries that only export the commodities whose prices are higher (basically, fuel and grains) are net winners, and they simply have higher international reserves. This means that they can have looser monetary policy, revalue their exchange rate, or lighten capital controls to preserve their “natural” balance of payments. On the other hand, countries that are net importers are in trouble. Because they have a worse net position, they have to balance it with one of three ways: sell off international reserves, raise interest rates, or impose controls on hard currency transactions. Since most countries consider foreign investment and imports a good thing, the latter isn’t really going to happen. However, the other two pose a challenge for the authorities, and it’s because of the exact same reasons as above.

If a Central Bank has enough international reserves, it can simply bite the bullet and let go of them to keep the economy on the same track. But if it doesn’t, or if it committed to not interfere in foreign currency markets (i.e. has a floating exchange rate), then it can either allow for a devaluation or raise interest rates. Raising rates is deflationary, but it is also contractionary - the economy would slow, or even enter a recession. However, a devaluation might also be undesirable (once again, see the post about Russia):

… if a large share of prices are set in international markets, then big fluctuations in the exchange rate can have a proportional impact in inflation. For example, a country that exports food and imports fuel would be terrified of a big devaluation (or not, depending on consumer habits). So right there, the Central Bank can want to keep movements to a minimum to fulfill half of its mandate. In many developing countries, the exchange rate acts as an anchor for inflation expectations (since its value is obviously stable), which means that the impact of a devaluation on inflation can be devastating to price stability. (…)

Meaning, inflation can increase due to a devaluation because either imported products get more expensive (once more) or because expectations go up - either way, exactly the opposite of what you want. The traditional choice, inflation vs recession, isn’t so clear cut anyways because devaluations can be recessionary (more detail in Russia post) for a variety of reasons: if the devaluation doesn’t increase exports but decreases imports, if the people who benefit from trade (i.e. “exporters”) have lower marginal propensities to consume than the ones who don’t (i.e. purchasers of imported products), or if it doesn’t decrease the demand for hard currency.

Conclusions

So, are higher commodity prices good or bad? It depends. If you’re an exporter of those commodities without inflationary issues, you’re at the best position possible. However, countries that suffer both inflationary and recessionary effects (most of the developed world, for example) will have to contend with simultaneous pressures to tighten and ease monetary policy, in response to each of those shocks. For developing nations, the sudden turn for the worse of their balances of payments might pose an even more uncomfortable dilemma, where the usual monetary policy question gets compounded by the urge to avoid the negative effects of a devaluation.

The correct response to the situation is not especially clear, particularly when the supply-side conditions might already be resolved by the time monetary policy has a clear effect. The main risk isn’t that an increase in wheat and gas prices will return the world to the 1970s, but rather that it proves the straw that breaks the camel’s back in terms of inflation expectations becoming unmoored from their previously stable footing. The risk for acommodative monetary policy is that it forces their hand for even more drastic corrections in the near future, rather than the direct effects on inflation itself. Regardless, it is not clear how big that risk is, or how to best avoid it.

Not a very satisfactory conclusion, but it’s better to just state the conundrum central bankers and governments throughout the world face, mention the risk and complexities attached to it, and leave it unanswered, rather than pretend that a highly complicated situation has a simple, clear-cut solution. . Perhaps complacency (or patience, depending on your perspective) proves wise, and issues resolve themselves. Or perhaps every second counts, and the next year see a return of the much dreaded stagflation with only a Volcker-esque “shock” capable of reigning prices in. At the heart of the paradox lies the fact that the preferences of policymakers play a big role: do they protect 2021’s rapid recovery (compared to the aftermath of the Great Recession), or do they protect their decades of effective stewardship over the price level? Monetary policy will face its greatest challenge in decades in 2022 - and it is in everyone’s best interest that they meet it

Important reflections here, thanks for the post.

I would say mixing absolute (comm prices) and relative (% price change aka inflation) measures in the same chart isn't the best choice though.