Special edition: Argentina says enough

The Argentinian government got crushed in the midterm primaries. It was their fault.

Argentina held primaries for the midterm elections last Sunday. Election primaries serve two purposes: to settle party primaries (a job they do poorly, since they only settled a handful of major nominations in the past decade) and to act as a trial run for the election, of sorts. Most polling (which is rarely made public and has made a number of high profile misses in basically every election so far) showed a relatively even race, with the governing Peronist party generally ahead by low single digits.

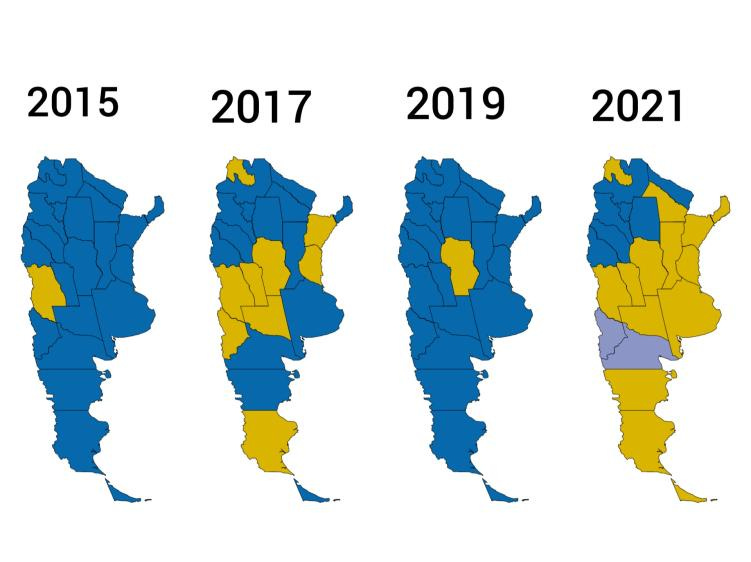

Then came election night on Sunday, September 12th and… chaos arrived. The President’s party finished ten points behind its rival, collecting only a third of all ballots - the worst performance by a united Peronism virtually ever. In a mirror of his stunning upset victory over center right incumbent Mauricio Macri two years ago, Fernández was thoroughly rejected by voters, losing in 20 of the country’s 24 provinces, and failing to capture the evening’s top prize: the Province of Buenos Aires, home to roughly 40% of the country’s voters and with a strong source of Peronist votes in the working class suburbs of the City of Buenos Aires.

The size of the Peronist party’s defeat cannot be overstated. The party got routed in long-held strongholds, like Misiones and Chaco, by double digits. It barely held on in Salta and San Juan, longstanding Peronist provinces, and got less than a majority in Formosa, personal fiefdom of caudillo Gildo Insfrán. The average vote loss compared to 2019’s primaries was 15 points - and over 20 in most of the party’s home turf. The party would also lose its 5 seat Senate majority if the results were repeated - and would be much further away from a quorum, let alone a majority, in the lower House.

Why did the party lose so terribly, and why was the defeat (not to mention its scale) so hard to foresee?. Let’s start with the latter. Considering pollsters made a similar, albeit much bigger in scale, mistake with their 2019 scenarios - predicting a 40-40 tie and instead getting a 49% to 32% blowout of the incumbent - polls and surveys are considered less than worthless. A strong vaccination drive in the past few months and a somewhat better economic situation, besides rampant inflation, was assumed to be an asset. Here’s the tough part: the sluggishness of the vaccination effort, coupled with unnecesarily draconian lockdowns and brutal police enforcement of them, was not popular - not to mention the scandals. The two biggest dents in the government’s credibility with regards to vaccines came early in this year and weeks before the election.

In March, a government-friendly journalist revealed that he had gotten a VIP vaccination because of his ties to the then Health Minister, Ginés González García. A series of interviews and research showed that roughly 3,000 vaccines (then exceedinlgy scarce in the country) were distributed among the upper echelons of the Peronist Party, including to friends and family of high-ranking officials. This came just as it was also revealed that the govenrment had basically blown off Pfizer and Moderna on deals for roughly 14,000,000 shots, at a time where the vaccination drive was running on fumes. The Health Minister, González García, resigned after weeks of downplaying the scandal to the media, and was replaced by his deputy Carla Vizzotti - whose parents, it turned out, were among those included in the VIP lists.

Plus, a handful of weeks ago it was revealed that, at the height of the 2020 lockdowns, the President violated them (and committed a federal crime that he, a law professor, had created) by hosting roughly a dozen people for his wife’s birthday. The picture was horrifically received, with a high profile political scientist putting it best: “the President used to have the image of a hustler, but a likeable one. This event puts him in the place of a grifter, a privileged person who screws other people over.”

Below: “positive assessment of the government stood at 32.2% of the citizenship in August 2021. How many votes did the government get? 32.2%”

These scandals, coupled with a horrific economic situation (four million people lost their jobs in 2020 and only about a third of them recovered them, plus more than 40% of the population in poverty and core inflation of 3% a month for the entire year) and a horrible campaign strategy of having high-profile candidates for Congress talk about sex and astrology on the media, cost the President’s party dearly. Indicators such as the Consumer Confidence (see graph above) and Trust in Government Indeces declined sharply, and the opposition had a savvy media strategy and offered a wide array of candidates in its primaries to attract all manners of voters: from anti-Peronist pro life hardliners to moderates and progressives tired of scandal after scandal.

For a party centered in the Buenos Aires Metro Area and its needs, the government got demolished there - losing an electoral stronghold 39% to 35% even after a single-minded pursuit of its working class votes. The govenrment lost the votes of the youth, despite campaigning on being “the party of sex” (in cruder terms) and making marihuana a campaign issue. This is without realizing that the key to the working class, and the youth, and everyone, doesn’t lie in grand pronouncements of national sovereignty: it lies in what commentator Carlos Pagni calls the “four i’s”. Translated, they’re the four Cs: crime, corruption, coronavirus, and CPI (“inseguridad, inflación, inmunidad, e impunidad”). In 2019, the Peronist party beat its opposition 60% to 24% in its core segment of the Buenos Aires suburbs, the Third Section; in 2021, it won by just ten points, 42% to 32%, and lost two million votes in the Province of Buenos Aires.

The Peronist party lost the youth, and the poor, not because of insufficient campaigning, but for a much simpler set of reasons: bad management. The Peronist party’s stated raison d’etre, and its biggest selling point in 2019, is its ability to govern and solve problems. But the handling of all the major issues was nothing less than atrocious: inflation is out of control and the government doesn’t have much of an idea to solve it, crime is seen less as a crisis and more as a fact of life (quizzed on the murder of a pensioner during a home invasion, the Security Minister said “Switzerland is safe, but it’s also boring”), the aforementioned scandals in coronavirus handling, not to mention things like forgiving an 8 billion peso debt from a government-aligned media mogul days before election day, tarnished the government’s reputation and made coronavirus containment a risky bet.

There is, however, another big news story here: the libertarian party. Its two main standard bearers, José Luis Espert in the Province of Buenos Aires, and Javier Milei in the eponymous City, performed significantly above the party’s paltry 1% finish in 2019: Espert got 5% of the vote, guaranteeing himself two seats in the legislature, and Milei got an unprecedented 14% in the nation’s capital. Now, the significance of Milei’s sucess cannot be overstated. Espert’s support follows very expected patterns: as a Cato Insitute type libertarian, he’s anti-welfare and in favor of low taxes, but he also favored abortion in 2019 and supports legalizing marihuana. He performed best in the wealthy suburbs of San Isidro and Vicente López, and worst in poorer areas.

Disclaimer: yes, I know it’s gauche to use my own tweet here, but it makes the point well - and in English.

In comparison, Milei did shockingly well: he got his highest marks in the poorest neighbourhoods of the City, and his lowest in the richest areas. He’s an odd fellow, with a positively Hoppean ideology: an economic minarchist and social reactionary, he’s still a populist, raging against the political elite “who are the only ones who prosper, at the expense of everyone else” and going after the government’s opposition viciously, calling its leader (Buenos Aires Mayor Horacio Rodríguez Larreta) a “disgusting bald turd”. Milei’s performance on the poorest parts of the City can best be understood as a thorough rejection of the President’s agenda, and on Peronism’s grip on the poor writ large: after a lockdown with its harshest effects on the poor and on small-scale retailers, an anti statist, individualist message might resonate the most, especially for an outsider who also attacks the economic failures of the President’s predecessors.

In conclusion, the midterm primaries were a thorough rejection of the economic and containment policies of the government. Lost support in its strongest areas and among its key constituencies disproves, evidently, the theory that the government should have focused on its core supporters and on doubling down on Cristina Kirchner’s figure. In fact, CFK’s record as a leader is incredibly overrated: after running Peronism through 8 elections, she only led her party to victory three times, and her center-right foil Macri (he is, unlike her, considered a do-nothing, know-nothing lightweight) won the other five.

Right now, Cristina and her allies have plunged the governing Peronist coalition into chaos, with most of the Cabinet’s hardliners (loyal to her over Alberto) handing in their resignations, and other powerful figures demanding the heads of Treasury Secretary Martín Guzmán and Chief of Staff Santiago Cafiero. If this is a cristinista putsch, the government may radicalize and attempto massively monetize the deficit to win back the millions of voters who deserted it - risking an eruption of inflation and worsening social and economic conditions, maybe even at the start of the actual election month (November). This would also make the path to victory even steeper: hardline Kirchnerism is extremely unpopular, even in diehard Peronist territories, and a lurch far to the Chávez-adjacent left would deal a killing blow to Fernández’s term.

Prospects for the government remain dire: most of the recovery has already happened, and supply-side constraints might make surpassing the current levels difficult. Underperforming economic output would also entail sagging employment and delays in improvements to social conditions, while welfare plans (even nakedly electoral ones) prove insufficient. Plus, the math is already hard: the government needs to flip back millions of voters who thoroughly rejected it, maybe for the first time in their lives, which might not even be enough, since turnout was historically low and the higher turnout in general elections (versus primaries) has benefitted the opposition by 5 points or so in all of the last four elections.

One of the main ideas to understand in Argentinian politics is the “hegemonic tie”: the country has two main coalitions (the Peronists and the anti-Peronists) who are both powerful enough to win elections and block their rivals, but not powerful enough to actually impose their agendas. This concept clearly ignores that one side is a corrupt, authoritarian, personality cult with backwards ideas about the economy, and the other proposes the necessary reforms to end a decade-long stagflationary episode. Argentinians have seen what the purest, most unencumbered version of Peronism has to offer - and it took the opposition’s banner of “enough”. The wanton greed, naked cruelty, and comical incompetence of the Peronist party might break this longstanding tie - in favor of their opponents.