Lately, I’ve been writing a shorter, narrower post focusing on one specific paper instead of usual deep dives. Last week, I wrote about whether members of the public find female economists more persuasive than their male peers. This is the tab with all the previous posts.

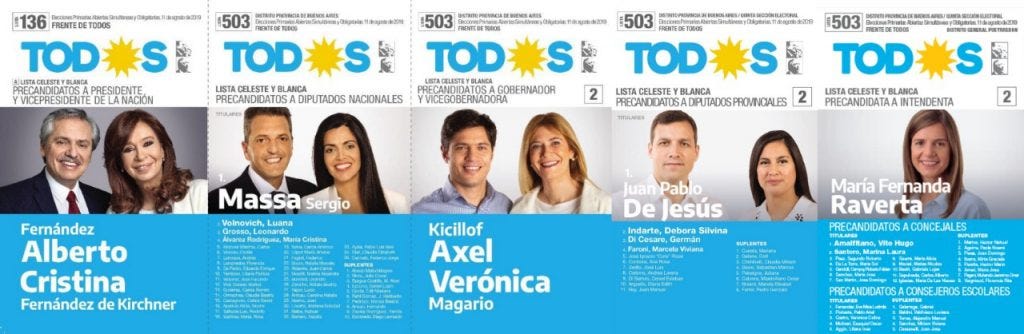

In what is surely a sign that global politics are in a good place, more-or-less unfounded allegations of voter fraud have become increasingly common among losing, and sometimes even winning, candidates - most infamously by Donald Trump, but also other such figures like Jair Bolsonaro, Benjamin Netanyahu, Javier Milei, and somewhat bizarrely former Argentinian President Alberto Fernández during the 2019 presidential primaries (which he won by a 16 point margin).

This has led, on the one hand, to attempts at rejecting the results of the vote; and on another, at preempting fraud by “election integrity” efforts at monitoring the polls in some way. While, in general, these are useless and more or less just thinly veiled attempts at rejecting electoral defeats, especially in developed, secure democracies, there is a real question of whether political parties monitoring election results does, in fact, have an impact on said results.

There is a paper that, in a way, tackles this question: “Who Monitors the Monitor? Effect of Party Observers on Electoral Outcomes” (2017) by Agustín Casas, Guillermo Díaz, and André Trindade. The paper examines the role of partisan election monitors on Argentinian election outcomes during the 2011 presidential election. To give credit where credit is due, I found this paper through this Substack post by Nicolás Ajzenman, an Argentinian economist writing similar posts to this one.

To understand the paper, first we have to understand Argentina’s somewhat convoluted electoral system. The country, much like the United States, is a democratic federal republic, and every four years holds presidential election. Unlike the US, however, there is no absentee or mail voting, and people get assigned a polling place by the government. Each province is divided, by municipalities, into various subdivisions, and within each subdivision people get assigned to a public school in the area (or private, if there aren’t enough of them). Within each school there are mutliple “tables”, each with one ballot box, and you get pre-assigned to them. This isn’t done by distance (my family has lived around the corner from a public school for 27 years and yet we’ve never voted there) or any real criterion, but rather, alphabetically - if your last name is Aalto, you probably vote in Table #1 of School #1 of your area, and if it’s Zyvborg, you probably vote somewhere else.

Then there’s the actual voting process: you get in line, wait, and then the poll workers ask to see your ID (a real national ID card, not those rinky dink ones the Americans use), and if it all checks out, you get an envelope signed by the poll workers and are let into the “dark room”, which is typically a classroom and has all the ballots. Then you place your ballot in the envelope, lick it shut, and place it in the ballot box. Because of Argentina’s strange rules pertaining to ballot design, each party supplies its own party-line ballot for every category, and split ticket voters have to literally split their tickets by bringing scissors (or cutting them physically), which can lead to various hijinks: people stealing a party’s ballots, parties running out of ballots, or improperly cut ballots that, by law, are not admissible.

At the polling place, there’s three types of people: the military police, who keep order; the civilian poll workers, who get summoned into it a la jury duty, and election monitors appointed by the registered political parties. The way the system works is that to vote you need sign-off from the actual poll workers, and their signatures are required on the election certificates; however, parties tend to hire their own people to monitor each table at each school in every district. They’re usually residents who vote at a nearby polling place and sympathize with the party, and their role is to keep the party’s ballots stocked, and then give the party seal of approval to the vote at the end of the polling day. Because parties don’t have infinite resources, and usually prioritize placing (paid) election monitors in competitive areas, then not every polling location has full coverage for every party, and this is especially true for smaller parties.

Now, the impact of these workers could be highly endogenous. In the City of Buenos Aires, you are more likely to vote for a right wing party if you live in the affluent neighborhoods on the city’s north, and more likely to vote for the Peronist party (or, somewhat bizarrely, Javier Milei) in the poorer neighborhoods in the city’s south. Of course, since the moderate right is popular in, say Palermo, and unpopular in say, Villa Lugano, then they would both have more election monitors and more votes in Palermo, and fewer of both monitors and voters in Villa Lugano. However, there’s a catch: people get assigned to the schools and tables they vote in within each district more or less randomly, and because of differences in coverage for the parties, there are schools where a party doesn’t have a monitor for every ballot box. If a given school has two tables but only one monitor, then the monitor is going to be assigned more or less randomly to one of the two - which means that, in many cases, whether a party has a monitor in a given location is unrelated to any actual drivers of party strenght (income, education, rural/urban, demographics, history, etc.).

Now, onto the 2011 election. There were seven parties contesting the election: first, the incumbent branch of the Peronist Party, FpV, headed by then-President Cristina Kirchner, which got 54.1% of the final vote (the largest first round election majority since 1973, and second-largest ever); in second place was Hermes Binner of the Progressive Front, an alternative center left coalition; third was the UCR candidate Ricardo Alfonsín; fourth, the provincial Peronist movement headed by Alberto Rodríguez Saa; fifth, former President Eduardo Duhalde’s Peronist splinter; sixth, the Leftist Worker’s Party, and finally, Elisa Carrio’s Civic Coalition.

The paper is quite simple: the authors downloaded 31,350 ballot certificates for 4166 schools in the Province of Buenos Aires, home to 40% of Argentina’s voting population. On average, each polling location received approximately 344 votes (representing 82% of registered voters), and only 2 of those were not declared valid. The number of party monitors per polling location ranged from 1 to 8, and the fraction of classrooms with a monitor per party ranged from 87% (FpV) to 2%. Let’s look at the results for each party conditional on it (not) having an observer on a given polling location:

So, for every party, support is higher in areas with election observers, and lower in areas without them. This, emphatically, does not prove causality - as mentioned previously, party observers are easier to find where a party has more supporters (who might volunteer for it and vote for it), and harder to find in places where a party is less popular. Nevertheless, because allocation of citizens to schools and of observers to classrooms is more or less random, then it is possible to determine a causal effect by comparing classrooms that have observers to classrooms that don’t have them. This is tested by the fact that there is no correlation between the first letter of the last name of candidates for all offices and their party affiliation, which should extend to voters.

The authors estimate that effect by regressing the number of votes that a given party gets at a given school in a given classroom by whether or not the party has an observer in that specific classroom, as well as a fixed effect for the party’s support at the school level, and a series of controls for the location (mostly pertaining to the presence of civilian election authorities, number of observers, the size of the electorate, and interactions between the observers and civilian authorities). This is done both for all parties as a whole, and for each party, given the large amount of data available. For party-specific estimates, there is also a control for whether the party is the only one with an observer present, which could be a sign that giving “free reign” to a given party might let it engage in illicit or unfair activities.

The results are quite simple: for the aggregate of all parties, without any controls, the presence of an observer increases their number of votes; controlling for school-level partisanship, neighborhood-level partisanship, and the controls, the effect size decreases to around 1.3% - in all specifications, with a high degree of significance. For each specific party, we find strong effects of having an observer on parties 1, 3, and 5, which have effect sizes of around 5.5% (party 1, the Civic Coalition), and 2% (for 3 and 5, which should be Duhalde and Binner respectively). None of the other parties had statistically significant effects on other specifications. In addition, there is no systematic and significant evidence that being the only party with an observer is beneficial to any parties. Lastly, and somewhat surprisingly, the cross-party interactions (i.e. whether party X and party Y (not) having an observer at the same time systematically benefits or harms one of them) are not significant for any specific parties, but are for all parties as a whole. This means that, if the activities of party monitors harm other parties, it is whenever the opportunity arises generally and not to harm or benefit one specific party.

These results replicate for legislative and senatorial elections, and also replicate if the dependent variable is vote shares and not number of votes. Using municipal-level data for the vote share of each party in the previous election, the authors find that the incumbent party fielding election observers does not have a meaningful effect on its vote share (controlling for baseline municipal partisanship), but that the observers of all challenger parties do by around 1.4% - the effect is bigger, but not significant, for close elections, which is due by the small number of close races (less than 10% of the total). Lastly, the effect of observers in municipalities where mayors had served two terms or more before the election is not different in any meaningful way from the regular incumbency effect for neither incumbent parties nor challenger parties.

This begs the question: why exactly is there an impact of election observers? The authors propose four channels: vote buying, turnout buying, ballot stuffing, manipulating contested votes, and stolen ballots. Let’s start with vote buying: it’s possible that local party bosses bribe voters into supporting them, and use the observers as a reminder. Is this true? Given the literature on clientelism, this kind of behavior would have to be greater in poorer districts - but the authors find no significant differences in this case. Regarding turnout buying, which is the same except friendly voters are paid to show up to the polls (and since observers have access to voter rolls, they would be able to check), and also ballot stuffing, the authors find no relationship between turnout and presence of an election observer.

Manipulating contested ballots is a classic. My dad was summoned to work at the polls in 2021, and remembers a hilarious moment where a group of Peronist ballots had been damaged, and the Peronist and opposition observers disagreed on whether they should be counted - the Peronists thought they should be thrown out, and the non-Peronists that they should be counted (they were counted). This is a classic task, and one that can be read as “harmless” - whether a vote is actually invalid or not might be a matter of genuine debate given some ambiguities in the law. But if we look at votes ruled invalid, challenged, or nullified, then there is no statistically significant relationship between one or more parties having observers at a given polling place and this outcome.

Lastly, destocking ballots - since the parties are responsible for providing their own ballots, and the observers have the job of verifying that they were not stolen and replenishing them if they were, then it is possible that observers simply allow (or even directly commit) theft of “absentee” observers’ ballots. Since it is not legally allowed to show up to a polling place twice, there are two options: first, voting for someone else; second, casting a blank vote. Considering that there are no cross-party effects of observers, then it’s hard to claim that voters switch votes - so the dominant effect has to be blank and not blank voter. In this sense, if a party has observers, then its vote share must increase (because it can replenish stolen ballots), whilst if it doesn’t, then blank votes must increase. For most parties, there is not a significant effect either way - meaning that the observers either don’t replenish or steal votes, or that the effects cancel out. However, party 2 (the national incumbent, aka FpV), then there is a very large, positive, and significant effect on blank votes: there being a mainline Peronist observer raises the share of blank votes to approximately 7%, which points to either allowing or directly committing ballot theft from parties without observers present.

But are we really sure that the effect has to be caused by observer behavior which is illegitimate in nature? It could mostly be people like my dad's observers, who just have weird ideas about civic virtue or whatever - could be that different parties systematically emphasize different standards for ballot for reasons related to ideology. One way to test this is whether municipalities with higher civic capital (i.e. more trust in institutions, more participation in civic life) have a different effect size of observer presence. The authors define civic capital as the presence of pro social trust and attitudes that help a society resolve the free rider problem (people using public goods without paying for them) in its institutions. The way they measure it is by looking at the ranking of municipalities by organ donor registrations - if the number of declared donors is in the top decile, the authors say it is high civic capital. Well, while there is an effect consistent with the previously mentioned ones in low civic capital areas, there is no effect detectable from election observers in high civic capital areas. This means that, generally, political parties do not make different decisions regarding ballots between areas, so the effect should be explained by illegitimate behavior: parties don't need to protect their ballots from outside interference in high civic capital areas, but do need to in lower trust or less developed municipalities and neighborhoods.

In conclusion, while there is some evidence suggesting that election integrity efforts can be fruitful, the truth is that they do not do anything to resolve the major concerns in conspiracy theories: vote buying, ballot stuffing, or vote count manipulation. Their only influence, that is on stolen ballots, is only possible because of the quirks in Argentina’s electoral system whereby parties must supply their own ballots. In provinces with single ballot elections, the observers would not have any meaningful effect, beyond shoring up popular legitimacy and buy-in on the election. This has been implemented in multiple provinces already, and has been proposed at the national level multiple times - currently, State Modernization Minister Federico Sturzenegger is pushing to have it included in an election reform bill.

To finish the post, some links

The paper in question

A blog post by Nicolás Azjenman (in Spanish) about the same paper

A paper by Asunka et al. finding similar results on the same topic from the 2012 Ghanian presidential elections

A paper by Azjenman and Rodrigo Durante about whether voting in dilapidated schools in a different Argentinian election punished a mayor with presidential ambitions - as well as another Spanish-language blog post by Azjenman about it

A paper by Casas, Diaz, and Mavridis about the influence of ballot design on presidential election outcomes

A paper by Thomas Fujiwara about how changing electoral systems in Brazil affected election turnout, election results, and policy outcomes

A study by Antenucci and Abdala (in Spanish) finding that one Argentinian province switching election systems (to a single ballot) in 2015 resulted in lower shares of blank voting