Inflation is a Four Letter Word

Can the Quantity Theory of Money still help us understand anything?

The Quantity Theory of Money might as well be one of the most misunderstood economic concepts out there, both by its proponents and by its detractors. Many say it can help clarify every economic phenomenon, particularly inflation, under the sun, while others claim it is a right wing fiction to simplify reality. Which side is right? Is either?

The cornerstone of the Theory is the equation of exchange, also known as the quantity equation: MV = Py, where M equals the supply of money, V is money’s velocity of circulation, P is the price level, and y is real output. The rationale here is simple: both sides are equal to Y (nominal GDP), since MV is the total amount of transactions in the economy and and Py is simply real GDP times the price level (y also equals Y/P). The equation of exchange is what’s known as an identity, since it's always definitionally true - it also means that using it cannot really yield much insight. For example, an increase in M could cause an increase in P - or in y, or a decrease in V. Without more detail, you couldn't ever make workable predictions or accurately explain past events.

The way “traditional” quantity theorists turned the equation into a workable theory was by adding assumptions: firstly, that velocity (V) didn’t change over the short term, but was subject to variations over the long term; for instance, due to cultural and/or technological changes (think credit cards), or general changes in technology. Secondly, that in what neoclassicals called equilibrium but Keynesians called full employment, monetary policy (i.e. M) couldn’t increase y. As a result, this means that when the economy is in equilibrium, any increases in the supply of money end up reflected only as higher prices. As a corollary, this also implies that (absent changes in V because of the factors mentioned above) over the long term any increase in the supply of money is reflected as a change in the price level.

This is why Milton Friedman’s famous quote “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” is followed by “in the sense that it is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” Holding velocity constant, the supply of money in the economy can either be spent on more things, or bid up the price of the same amount of things.

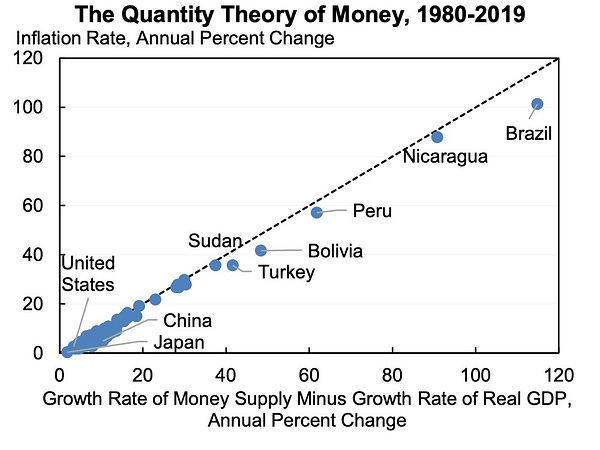

Does the theory work? Over the really long term, it does, at both high and moderate to low rates of inflation. However, if the time horizon is narrowed, the fit gets worse, and it becomes especially bad for the US over the short term. Why is this? Firstly, and obviously, the second assumption is weakest: the economy is not always in equilibrium, which means monetary policy can cool it down or heat it up as needed - resulting on either higher or lower real output (Friedman thought it could only stimulate real output but that’s neither here nor there).

Secondly, as seen above, the velocity of circulation of currency can actually change - a lot. In fact, it changes both over the long and over the short term, which results in predictions being less good than they otherwise would be. A good example is 2020: the supply of money increased greatly in most countries, as Central Banks “printed more money” to prevent a deeper recession, but prices didn’t increase (right away, at least). The reason why is that, at least for most of the early pandemic, people held a lot more cash than usual - both because they didn’t have as many things to spend it on and because they weren’t sure they would, for instance, remain employed. A combination of a growing (well, recovering) economy and lingering uncertainty means that the price level won’t absorb the full shock. For the US in particular, there was also a methodological change in how the supply of money was calculated right in the middle of the pandemic, which for some reason they haven’t corrected in older data (i.e. data from before 2020 and data from after 2020 use different methodologies).

There’s also some big methodological concerns. What is M, exactly? And does y stand in for supply or for demand? Well, as we said, the quantity theory rests on Y = Y - that is, spending and output being equal in nominal terms. It wouldn’t really make sense for MV to represent output, so it has to be spending - or as a Keynesian would put it, “aggregate demand” (not exactly but still a useful comparison). This means Py has to be “aggregate supply”. But how do you incorporate fiscal policy into this? Because it obviously means MV is going up (well, unless people just hoard the money), then you’d represent it as an increase in M - which is not precisely uncontroversial.

Exactly what is the supply of money is a whole story: there are various “levels” of money, each with different degrees of flexibility and each more removed from the Central Bank’s grasp than the last - currency in circulation (M0), currency in circulation and overnight deposits (M1), currency in circulation, overnight deposits, and short term fixed deposits (M2), and then higher monetary aggregates that include financial assets of various maturities. Which one to consider as “M” is fraught, because while M0 or M1 might be more theoretically pure, they’re not especially good predictors of inflation (plus the US recently redefined M1 without adjusting the older data, for some ungodly reason, so it’s a whole mess). There’s also the question of whether banks act as creators of money or just as intermediaries, i.e. if they loan out their deposits (intermediaries) or if they create currency under profit constraints. The view that everyone agrees is incorrect is that of the money multiplier, i.e. that banks simply loan out a fixed percent of the money the central bank creates. The banks-as-intermediaries view is contested (for example in McLeay et al. 2014, in this Deutsche Bundesbank 2017 report, or you can read a more accessible Twitter thread by George Selgin, with replies from various economists and opinionated individuals on nearly every tweet) but the monetary multiplier view is generally rejected.

Exactly what V means is another handful - and it depends on what definition of M you utilize. Of course, the traditional Quantity Theory assumptions about it being fixed in the short term and variable in the long term don’t really hold, because an economic shock might cause agents to demand more cash in anticipation of future events. For example, if the economy enters a recession (and there is no countercyclical policy), then people would spend less and “hoard” cash more, simply out of fear that they lose their job. So increases or decreases in velocity can happen regardless of “structural” changes such as new technologies, or a more “thrifty” culture. Also, especially at higher levels of inflation, velocity might be correlated with the inflation rate - meaning that an increase in the supply of money might raise inflation twofold, both directly through the money-prices relationship and indirectly through higher velocity. Consequently, it’s possible that velocity increases when policy is loose because even more inflation is expected - ergo, more money results in more money chasing the same amount of goods more quickly. Of course, this evidence coming from Argentina doesn’t say a lot, because the average inflation rate for the country is in the 100% area - meaning that the money-velocity-prices circuit might “start” at, say, 15% a year or at 50%.

Lastly, I think the more hotly contested issue is whether or not monetary policy can increase or decrease real incomes - i.e. whether monetary policy is neutral or not. Macroeconomists traditionally agree on two things: money is neutral in the long term but not in the short term. The first term means that increasing the amount of money in the economy doesn’t increase the amount of goods (and services) in it over the long term, which are thought to be determined by “real” factors (Post Keynesian economists reject this view, but theirs is not a mainstream opinion). The second part means that, despite it being impossible to make the economy richer by printing more money, you can keep the economy as rich by printing it - monetary policy can smooth over recessions and inflationary periods. To quote Scott Sumner “you can’t print your way to prosperity, but you can print your way back to prosperity.” There is some evidence in favor of these claims (Robert Lucas gave his Nobel Lecture about the topic).

A related topic is monetary superneutrality, i.e. whether inflation has an impact on the real economy. That is, it could be the case that printing money doesn’t influence growth, but inflation does - for example, by forcing people to invest in capital over financial assets (a positive effect), or by shrinking the financial system (a negative effect). The postulate that inflation has a positive effect on growth is known as the Tobin Effect, since Nobel Laureate James Tobin proposed that inflation could increase growth by forcing investment in capital. In theory, this can or cannot make sense: if you add more assets, or make investment a choice between savings and consumption, inflation either doesn’t impact or reduces growth. Of course, empirical evidence from Argentina (you guessed it) points to superneutrality being fake and the Tobin effect being real - but with a negative sign, since it increased investment in real estate and US dollars over “productive capital” and even financial assets. Once more, the existence of superneutrality is definitely not uncorrelated with the “inflation regime”: higher inflation rates definitely have negative effects on real variables (due to the difficulty of deriving information from noisy nominal variables), while lower inflation levels probably result in superneutrality.

So, summing up: is the Quantity Theory of Money correct or not? Well, of course the equation of exchange is always true, since all the variables are defined that way, but that doesn’t tell you a lot about anything. However, it’s seen that, even absent all the thorny methodological issues and the complicated questions about neutrality, superneutrality, intermediation, and velocity, the evidence is a mixed bag. In general you can say that the theory holds over the long term, and it sometimes holds over the short term as well. But absent clearer definitions regarding when velocity changes and when money (and prices) are and aren’t (super)neutral, then the theory cannot be said to be correct. Of course, a final issue remains: monetary policy cannot always control inflation when fiscal policy comes into the mix. But no spoilers for future posts!

What to read?

The linked threads by Jason Furman and George Selgin

My previous blog post about Argentina’s demand for US dollars

Theory:

McLeay, Radia, & Thomas (2014), “Money creation in the modern economy”

Lucas (1995), “Nobel Lecture: Monetary Neutrality”

Orphanides & Solow (1990), “Chapter 6 Money, inflation and growth” in the Handbook of Monetary Economics, Volume 1

Evidence:

McCandless & Weber (1995), “Some monetary facts” (PDF download alert)

Argentina

Burdisso, Corso, & Katz (2013), “Un efecto Tobin perverso: disrupciones monetarias y financieras y composición óptima del portafolio en Argentina” (in Spanish)

Do PKEs really reject that money isn't neutral in the long-run? Maybe it's because I just took Intermediate Macro at my university, but money being neutral in the long-run and non-neutral in the short-run is just very intuitive I feel.

A deep understanding of the QTM is essential for sound monetary policy!

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/the-feds-monetary-policy-from-the?s=w