I'm sorry, did I break your concentration?

Competition is down across the US economy, with disastrous consequences for Americans. The White House is on the job.

Last week, Joe Biden’s Council of Economic Advisors announced a series of policies designed to promote competition in many US industries, most noticeably healthcare, both through regulation and deregulation. Competition is always a good thing, as any Econ 101 course will tell you, but reality is often messy - take a look at patents, or natural monopolies. Is the state of affairs as dire as the White House claims, or is this just some far left hysteria? And what are the benefits of action - or the costs of inaction?

The state of affairs

Since the late 1990s, over 75% of US industries have experienced an increase in concentration levels. We find that firms in industries with the largest increases in product market concentration show higher profit margins and more profitable mergers and acquisitions deals. At the same time, we find no evidence for a significant increase in operational efficiency. Taken together, our results suggest that market power is becoming an important source of value.

From: Grullon, Larkin, & Michaely (2019)

There are some conditions under which market concentration is “good”, generally because a given merger lowers prices as a result of larger firms being more efficient than smaller firms. But this isn’t actually happening: concentration increased margins but not efficiency, meaning it led to higher prices. To be fair, some of the increase in profits was caused by productivity, but that small effect vanishes when you adjust for whether or not any industry requires a lot of capital, since they’re more efficient on average and also tend to have much bigger (and fewer) firms.

These increases in profits, as a result are coming mostly from higher than necessary prices, and are frequently benefitting larger, older firms. Thus, big and established companies are concentrating larger and larger shares of output in a given industry. Importantly, there isn’t much difference between industries, so it’s not that some parts of the economy grew stagnant and uncompetitive while others flourished.

This concentration, and this has to be emphasized, has not occurred due to natural monopolies or economies of scale. Most industries had significant increases in concentration at the same time and at a similar pace across the economy. This didn’t happen because some markets are so expensive to enter that they can only fit in a handful of firms, or that very productive firms are beating all their competitors. If this were the case, those markets would be much more productive and there would be efficiency effects, but as mentioned above, there aren’t any.

Consumers or shareholders

This has an evident implication: people who own shares of established companies are making a lot of money off this, while it’s almost definitely costing consumers a bundle. This means that the gains from bigger firm profits aren’t equally spread, and since a large number of mergers increased prices (with an average of 7%), then it’s money that’s going straight from consumers and into the pockets of (on average, richer) shareholders. And even in markets where the highest performing firms are getting bigger due to being much more efficient (say, Amazon in e-commerce), this effect is still present. For instance, the price of Chilean birth control pills declined by around a third when the three farmacy chains that run 92% of the market competed between them, but then increased by 40% in nearly one day when they fixed prices.

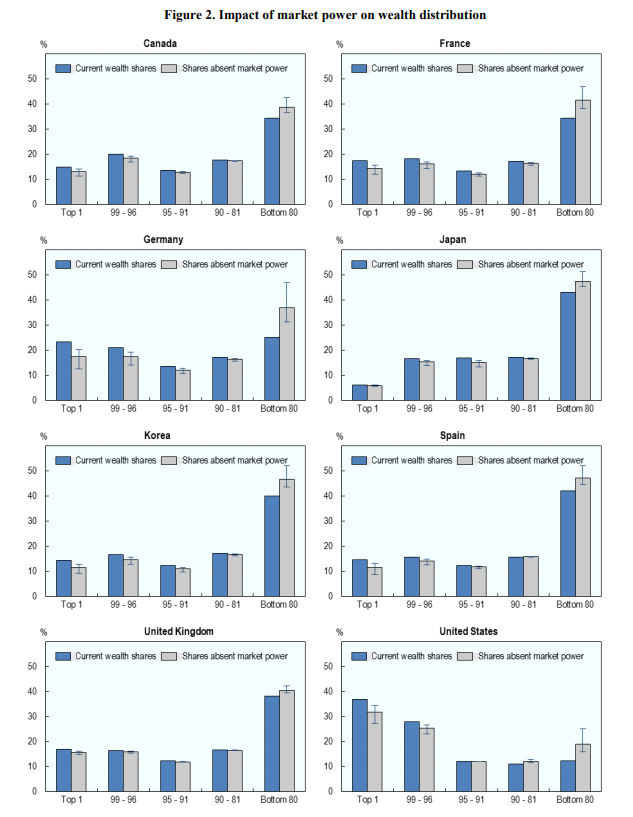

Income and consumption distributions are biased in favor of the rich: while the top 20% accounts for something along the lines of 35% to 40% of consumption, and 45% to 50% of income, it also owns more than three quarters of all corporate equity. In consequence, the benefits of a “corporate bonanza” are mostly concentrated in the top percentiles of the income distribution, whilst consumption is not - because the owners of stock and equity are disproportionately very rich. Reducing market power would immediately move 3% of national income from the top 20% to the bottom 80%, and it would also considerably reduce the returns from investment income - preventing a further rise in inequality and maybe even reducing it down the line.

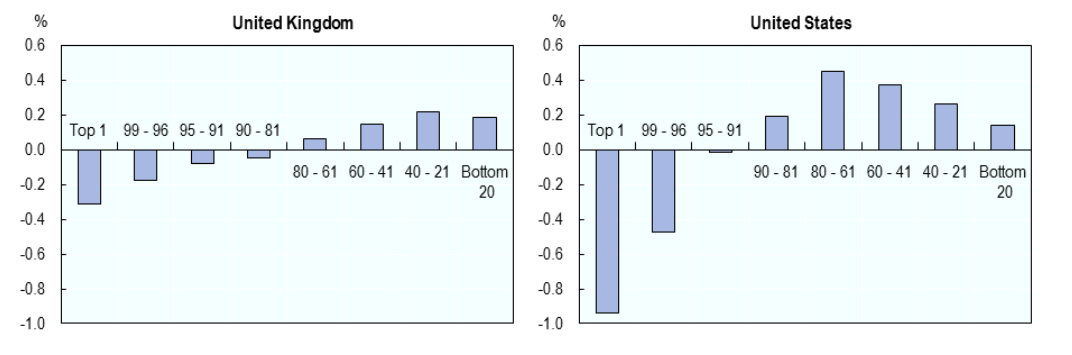

Across the OECD, market power has increased the wealth of the top 10% by between a tenth and a fifth, while reducing the income of the bottom 20% by between 14% and 19%. Redistribution based on market power would “harm” the top 10% and transfer wealth and income to the poorest 20%. Using the UK as an example, cutting the mark-up on products by 1% would increase the wealth of the poorest 20% by 0.19 percentage points, and raise their share of national wealth by about 22%. This isn’t to say that any competition policy can be justified for its distributive impacts, but rather, that the incredibly disfunctional markets created by lack of competion also have an enormous redistributive component. Similar conclusions can be drawn for nearly all OECD member countries where this phenomenon occurs.

This also ties with the fall in the labor share of income: some markets have enormous firms dominating them, and they generally pay bloated salaries to their staff. As a result, the majority of income disparities seem to be within industries and not between them, which means it generally has to do with firm “hierarchy”. For instance, the pay ratios between janitors and CEOs is roughly constant across industries, so typically there should be differences based on each industry but mostly due to firm size. This also means that a lot of workers simply move towards very small and unproductive firms, that pay lower wages on average. In consequence, both labor and productive capital (owing to less investment, as will be discussed later) are being sidelined in national income in favor of corporate profits.

Rents are the name of the game

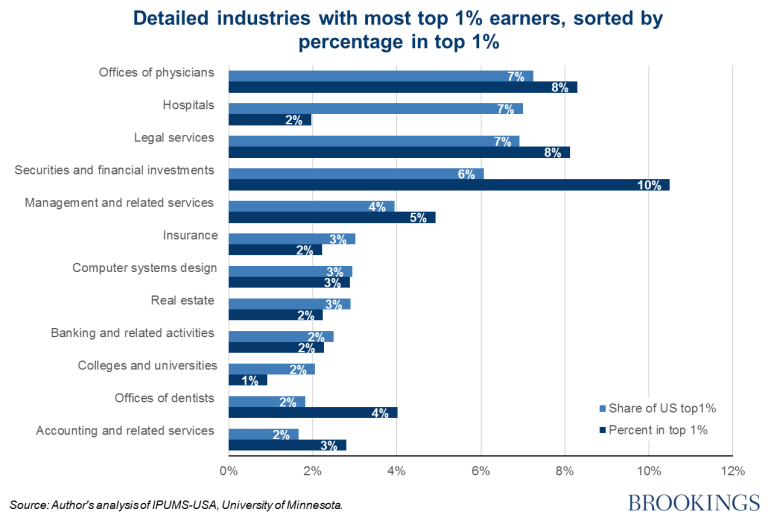

Certain industries also have extraordinarily high levels of gratuitous pay, i.e. income that is much higher than can be explained for the skills of the worker. For instance, people who work in the oil industry, banking, law, or hospitals (!) earn much higher wages than can be explained by all other categories other than industry, while people who work in education or food services make much lower than they should.

And if you look at what people in the top 1% do for a job, you might be surprised: 7% of all people in the top percentile are doctors, another 7% work in hospitals, and 2% are dentists. Why is 16% of the top earners employed in healthcare? This is particularly weird considering that the rest of the top 1% are much more obvious: real estate workers, lawyers, accountants, tech workers, finance types, etc.

The reason why is simple: lack of competition. Medical professionals, as well as lawyers and accountants, are licensed occupations. Whilst some of the requirements for physicians and legal professionals are based on ensuring competence, often they’re just the product of state-level lobbying to reduce competition; a classic example is the requirement for doctors to complete four years of college, then med school, and do a residency in an (artificially small) number of hospitals - which are much higher than in comparatively developed nations.

In fact, most of the work that only lawyers and doctors are allowed to do could be performed just as well by someone without a legal degree. This points to a general trend: 52% of licensed workers have higher education degrees, versus just 38% of the workforce. And licensed workers make, on average, 28% more than unlicensed workers, and 10% to 15% more after adjusting for their higher level of education.

This makes occupational licensing a classic, clear-cut case of rent seeking, i.e., the pursuit of economic benefits that are not “earned” through fair competition. but rather unearned and stemming from sitting on a rare resource. The most classic example of rent seeking, taxi medallions in New York City, is actually a type of occupational licensing. Besides their rent seeking in the housing market, the rich are also obtaining unearned returns by shutting down access to the top professions: to them competition means just for low-wage service workers, but not for the top professions.

But it doesn’t just happen at the worker level, either. Remember how hospitals have a very large “unearned” wage premium? Hopsitals themselves are operated by private corporations and only built when a local government body rules that there’s a need for them, meaning that lobbying has artificially reduced the supply of hospitals. This is a consequence of both market consolidation in the hospital industry, and certificate of need laws that artificially reduce supply in the field.

Finally, the financial sector itself is not, in fact, sustained by its superiority to other options, but rather, through government subsidies to various types of loans, and regulations allowing only a certain sliver of rich investors to enter the highest-performing funds.

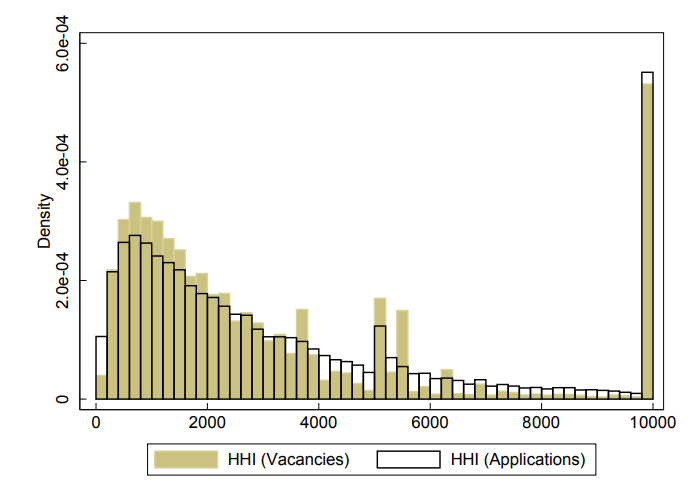

Labor markets are concentrated too

Since hospitals only employ licensed professionals, and they themselves are “licensed” as institutions, and since highly concentrated fields enjoy large wage premiums, then working for a hospital must rule, right? Wrong. In fact, concentration in the hospital sector has significantly reduced, not improved, the earnings of nurses.

This is a direct result of monopsony, basically a “monopoly” of demand. Just like monopolists can set prices that are too high, since there’s nobody else you can buy from, monopsonists can force prices way down. Medicine are a very obvious example: nursing is a licensed profession, but they can’t do many tasks due to licensing requirements for doctors; additionally, since they’re only employed by hospitals, then their wages are pushed down. In fact, hospital mergers tend to lower the salaries of nurses significantly, due to the market power they have.

The results have been large: workers seem to be about 17% more productive than what their salaries imply, due to their bargaining power being severely constrained. Plus, workers might simply be unable to escape monopsonists because of the enormous costs of relocation, that are both tied to out-of-control housing costs and to, ironically enough, ever-expanding occupational licensing regulations that could prevent them from independently exercising their trade.

One further source of monopsony power that isn’t related to market concentration by is tied to lack of competition was also tackled by the Biden White House: non compete agreements. Simply put, a non-compete is a contract forcing workers to agree to not take another job in a given sector.

Ideally, they would prevent high-level workers entrusted with sensitive data to not disclose it to competitors, but in practice they cover more than 30 million people, a huge number of which are low-level employees, who are nevertheless forced to sign non-competes at the same rate as high-level employees. This, and a number of other practices such as making non-competes mandatory in states that don’t enforce them, or forcing workers to sign them after accepting a job, points to them being simply a tool to stack the deck in favor of employers during bargaining with their employees.

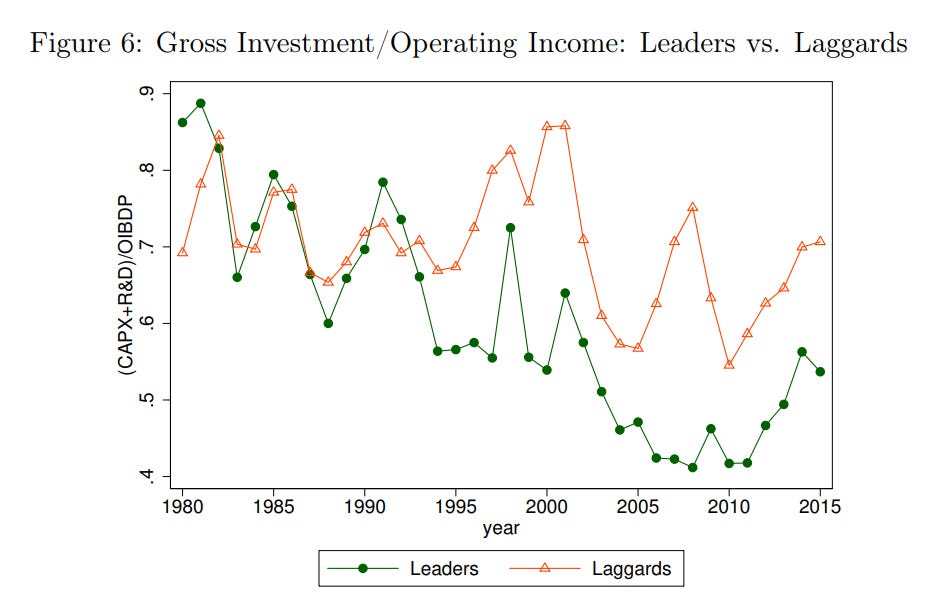

More concentration, less innovation

In general, very concentrated markets have lower investment than competitive ones, both in R+D activities and in other productive activities, and this is especially caused because of the lack of incentives market leaders have: investment strengthens the position of a company in an industry, and big leaders in uncontested markets simply don’t have them.

The relationship between innovation and competition, particularly, is fraught. The most obvious reason is that highly innovative markets could have firms that are too efficient to compete with, leading to more innovation in concentrated markets. But it’s also obvious that highly concentrated markets don’t have many incentives to innovate, whereas highly competitive ones do. In addition, monopolists might actually want to innovate to preserve their position, especially if they acquired it via innovation.

As most complicated relationships in economics, innovation-competition seems to be an (inverted) U-shape: industries that are very competitive incentivize innovation, but firms that are “falling behind” aren’t really incentivized to innovate, so the effects balance out in both extremely competitive and in extremely concentrated industries.

Empirical evidence has, multiple times, pointed to there being a generally negative relationship between innovation and competition, mostly because not very many markets are that competitive in the first place. This is especially puzzling because very large firms would stand to benefit the most from innovation, given that they have the most resources for it in the first place and the stand to lose the most.

Another part of the explanation is declining entry: firms are entering the market at a slower pace. Even the oldest, most basic economic theories point to more contestability (i.e. more ease of entry) of markets forcing different, more “competitive” behavior even when no firms are actually entering. In the pharmaceutical industry, for example, big firms actually paid off smaller ones to not enter the market in agreements known as “pay-for-delay”, which are actually responsible for reductions in R+D investment literally right after the agreements are signed.

The slowed entry of firms into markets is especially concerning, given that it also coincided with a much lower propensity of small firms to grow fast. This resulted in slower job creation, especially because many of the small firms that are created are actually small, “be your own boss” type establishments without much propensity for growing.

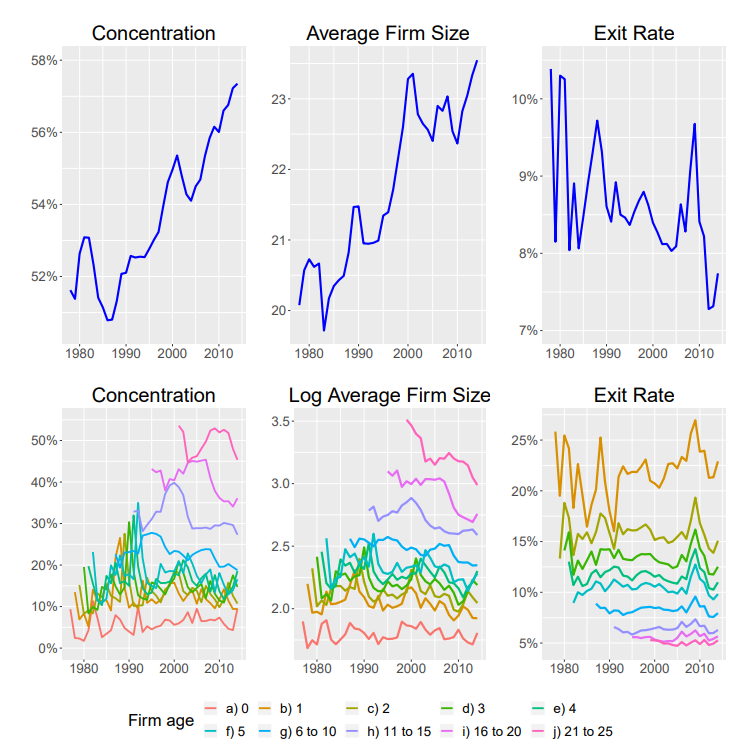

Why is competition decreasing so much?

There are basically three explanations for the lower rate of competition across US industries. We already know that this isn’t because of changes between industries, since it has affected them all, and that it doesn’t have (much) to do with technology.

The first is that, simply, the government has fallen asleep at the wheel and has both, simultaneously, enforced regulations too much and too little. On the latter, the government appears to have allowed too many mergers and acquisitions that impede competition and relaxed antitrust enforcement too much, leading to collusion between firms being more easy as well. On the too much side, occupational licensing laws and other rent-heavy regulations have been considerably expanded, leading to smaller battlefields for the bigger and bigger companies (and richer individuals) that fight in them.

The second reason stems from technology, but in a not very roundabout way. Advancements in IT meant that companies that were somewhat more efficient could grow very quickly, turning many markets into “winner take all” situations. This doesn’t mean that industries get more efficient, but rather that they are dominated by firms that were the most efficient.

A third explanation, that could square the lower firm entry, is demographics. Lower job force growth leads to more competition for labor, which hurts newer firms. This means that firms that are about to enter are discouraged, which increases the market power of incumbent firms, which start growing and getting older and bigger. Concentration plays both ways here: on the one hand, as mentioned in the sentence literally before this, slower population growth (or job growth force) leads to concentration. But additionally, concentrated markets also have advantages for bigger firms when they compete for labor, which is why many of the larger firms pay gratuitously high wages across industries. This also lowers exit rates, since successful, established firms tend to not go bankrupt very often, and increases firm size, because there’s no smaller underdogs fighting tooth and nail for every customer.

Conclusion

In conclusion, concentration is dangerously higher, and it’s real bad. I won’t go into all that much detail about what his Executive Order does (you can find that here), but it generally aims in the right direction: bolstering competition in stagnant industries, tackling rent seeking behavior by both large companies and individual professionals, and mandating more scrutiny and transparency to actions that might stem from or increase concentration.

This also has large implications for economic policy: as seen above, it could assist his goal of reducing income and wealth inequality, improve innovation and dynamism, and strengthen the labor market (which also reduces inequality). All in all, this seems like a solid course of action: focus on the forms of competition that are most directly harming American consumers rather than dubious pundit-pleasing wild goose chases of politically disliked firms. It shouldn’t be controversial to say that making hearing aids cost hundreds and not thousands of dollars is more important than tackling the scourge of Amazon Basics.

Sources

Introduction

Grullon, Larkin, & Michaely (2019), “Are US Industries Becoming More Concentrated?”

Blonigen & Pierce (2016), “Evidence for the Effects of Mergers on Market Power and Efficiency”

De Loecker, Eeckhout, & Unger (2020), “The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications”

Inequality

Ennis, Gonzaga, & Pike (2017), “Inequality: A hidden cost of market power”

Rent-seeking

Furman & Orzsag (2015), “A Firm-Level Perspective on the Role of Rents in the Rise in Inequality”

Brink & Hammond (2020), “Faster Growth, Fairer Growth - Part 3: Liberating the Captured Economy”

Rothwell (2016), “Make elites compete: Why the 1% earn so much and what to do about it”

Labor markets

Sokolova & Sorensen (2020), “Monopsony in Labor Markets: A Meta-Analysis”

Marinescu (2021), “Boosting wages when U.S. labor markets are not competitive”

Azar, Marinescu, & Steinbaum (2017), “Labor Market Concentration”

Krueger & Posner (2018), “A Proposal for Protecting Low-Income Workers from Monopsony and Collusion”

White House Concil of Economic Advisors, (2016), “CEA Isue Brief: Labor Market Monopsony”

Innovation

Gutiérrez & Philippon (2017), “Declining Competition and Investment in the U.S.”

Li, Lo, & Thakor (2021), “Paying off the Competition: Market Power and Innovation Incentives”

Why?

Bessen (2016), “Accounting for Rising Corporate Profits: Intangibles or Regulatory

Rents?”