Confidence Men

Lydia Tár, Marcel Duchamp, and The Banshees of Inisherin walk into Silicon Valley Bank

You want to dance the mask, you must service the composer. You gotta sublimate yourself, your ego, and, yes, your identity. You must, in fact, stand in front of the public and God and obliterate yourself.

Tár (2022)

Silicon Valley Bank collapsed the other day, and everyone’s been talking about it since - why did a bank run happen? Is a financial crisis next? What’s going on, like, in general? And I find the situation interesting, so here we are.

Jerome lied, SVB died

The business model of a bank is simple: loan money to people over a long time, which makes you money, and then get money that people deposit into the bank because it’s a useful service they might like. Because most depositors don’t really need all their money at once, and you get cash flow from new deposits and interest payments, loans can be much bigger than deposits. There’s this dumb controversy over whether banks loan their deposits, or whether they deposit their loans, or maybe they just loan as much money as they want and deposits are kind of there, but it’s besides the point. Now, because sometimes loans aren’t enough, the bank can spend the cash it gets from depositors (i.e. “liquidity”) on other things - usually assets that protect its portfolio, so it doesn’t start bleeding out money if things go badly.

Now, a bank can go out of business, clearly. The first reason is insolvency: it just makes too many bad loans and bets on too many bad assets, so it runs out of money. The second reason is iliquidity: the bank has money, but it doesn’t have cash, so if too many people want to withdraw, it collapses. This is called a bank run, and they’re so important the latest Nobel Prize went to their study - the main takeaway is that they’re maybe rational maybe irrational, but they emerge because of expectations: people either trust everyone to not withdraw, so they don’t, and the bank stays afloat, or they fear a run will happen, so they run too, and the bank goes under.

Why did Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) go under? You can read a general outline by Noah Smith, or a more in-depth explainer by financial news treasure Matt Levine - or a more data-oriented one by my friend (and friend of Paul Krugman) Joey Politano. But the broad outline is that SVB had most of its depositors be tech related, most of its loans be to those companies, and most of its assets be treasury bonds (and also random stuff like mortgage backed securities - all very safe). The problem is that the tech industry is currently getting liquified by higher interest rates, and the assets they chose as hedges are also getting hammered by monetary policy. So SVB wasn’t an illiquid but solvent bank - it was an insolvent (i.e. broke) bank, and it has been insolvent since February. The bank run seems to have happened because a lot of tech types got spooked and started worrying their bank might go under - which made it go under because tech types are all very attuned to each other’s opinions, and because basically nobody “normal” had deposits at SVB.

Now the bank has been taken over by the FDIC and it’s been bailed out (yes it is a bailout), so they’ll insure everyone’s deposits up to any amount. The next step is either they sell SVB for its parts, or they sell the bank to another bank (or to Elon Musk), and everyone gets continuity. HSBC bought the British SVB for a whopping one pound (around one dollar). Either way, it’s unlikely people’s money just vanishes, and I don’t think there’s gonna be a financial crisis - few large banks are extensively tied with SVB and the small banks likelier to face stress soon aren’t as horrifically incompetently run. Plus, the bank run happened pretty much exclusively due to the way Silicon Valley investors behave - it was all over Slack chats.

This is my vibecession! Mine!

One of the best movies of 2022 was Tár, a critically acclaimed darling that did not win any Oscars but most certainly deserved some. The movie follows orchestra conductor Lydia Tár, who is considered the world’s best and is a highly acclaimed composer, as she gets outed for having an inappropriate relationship with a conductor she was mentoring. After the facts of their relationship emerge, Tár is engulfed in scandal and loses everything - family, job, and reputation.

At the center of the movie is Lydia Tár herself, a commanding presence in the musical work - admired by students, respected by colleagues, and venerated by the public. Except her status is illusory - both because of her heinous deeds and because it is quite clearly an illusion, as her entire self is a carefully constructed persona to triumph in the world of music; her real name isn’t even Lydia Tár, but rather Linda Tarr. In a George Santos cum Roger Tichborne story, she made up her entire identity.

As in the Berlin Philharmonic, there is another carefully constructed persona conducting the global economy: the Federal Reserve. The Fed’s role, as I’ve written previously, is to conduct the vibes of the economy - the Fed is saying they’ll cause unemployment to go up, which results in people taking them seriously, and therefore in actual recession fears materializing in a perfectly sound economy. If the Fed wanted to, they could push it so hard an actual recession started, even without any actual further rate hikes.

A lot of this comes down to the fact that what the Fed says tends to overpower what it does - Fed policy actions that come with statements affect markets more than those without, simply because Fed statements are valuable, previously unknown information. Knowing what the Fed will do is as important as knowing what it is doing - strong labor market reports tend to depress financial markets because the Fed has signaled it wants a weaker labor market, which means rates will be higher. But if the Fed stopped talking about job openings (which look “bad”) and instead about quits (which look “good”), then strong labor market numbers would stop bumming out investors, because quits are back to pre-pandemic levels (of sorts) and so the labor market would not be considered inflationary under those measures.

The power of central banks to control the economy by controlling the vibes is unmatched. I follow fashion content, as you might now, (and this isn’t just trends - it’s stuff like haute couture runway shows) and everyone is talking about the looming recession. It’s on film discourse, it’s on media discourse, it’s everywhere. And all of it comes from the Fed. Before late 2021, nobody was talking about a recession, because the Fed hadn’t said it might want one. The best way of putting this comes from Paul Krugman:

You may quarrel with the Fed chairman's judgment--you may think that he should keep the economy on a looser rein--but you can hardly dispute his power. Indeed, if you want a simple model for predicting the unemployment rate in the United States over the next few years, here it is: It will be what Greenspan wants it to be, plus or minus a random error reflecting the fact that he is not quite God.

The Fed’s power goes both ways. If it’s believed that the central bank won’t do anything about inflation, it spirals out of control. And if it’s believed that it won’t do anything about deflation, countries enter decade-long slumps. Look at Japan, a poster child for this kind of dynamic: the Bank of Japan was extremely aggressive about not letting inflation go up, which resulted in a decade of too-low demand, which resulted in a stunted economy. Ben Bernanke called for “Rooseveltian resolve” (like the commitment to end the gold standard that ended the Depression) and Paul Krugman implored them to “be irresponsible”. The same was true for the post-2008 American economy - they should have simply printed more money.

But the thing about the Fed’s indisputable power - it’s built on an illusion, much like Lydia Tár’s power. With just a few wrong moves, the world’s most powerful financial institution can crumble, just like its best conductor can.

Dadanomics

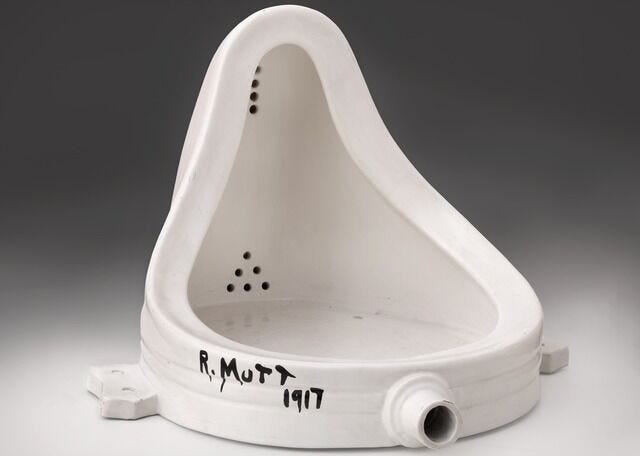

A century and change ago, artist Marcel Duchamp submitted a signed urinal to an art competition. The point he attempted to make, and which he continued making throughout his career through the ready-made genre, was that the line between art and object is mostly illusive - what separates a urinal from a work of art is intent, just like the separation between a Jackson Pollock and a mishaps with the watercolor board. A toddler couldn’t have done that because a toddler couldn’t have chosen to do that - what matters is the social relationships underpinning “art” and “artist”. Regardless of whether Duchamp was a true artist or an inflamatory sophist, the truth is that he was probably right - what we consider art, even good art, is mostly defined by conventions and norms. Impressionism was considered bad by critics, and the term was originally intended as an insult!

The power of the Central Bank is constructed in a similar manner. In the Krugman piece linked above, there’s an interesting tidbit: Old Keynesians didn’t consider that monetary policy could affect the economy, so they delegated most of the powers of stabilization to fiscal policy, and the Fed kinda impotently flounced around for a while. Of course, this was a matter of big debate, with the Monetarists (big surprise) thinking that monetary policy could actually accomplish things by setting interest rates. The big moment where the Fed definitively became the preeminent macroeconomic institution was the Volcker Shock, which was extremely painful - a prolonged recession followed extremely high interest rates.

This is the matter of credibility: the Fed promised to do “whatever it takes” to bring down inflation, and because it didn’t have an established track record of doing so, it had to go all out (forgive me master). It had “to demonstrate its willingness to spill blood, lots of blood, other people’s blood” - and to keep the hemorrhage going. The problem with big shocks is that you eventually run out of other’s people blood - Ronald Reagan tried to strongarm Volcker into not raising rates in 1984, which Volcker wasn’t planning on anyways. The Fed’s independence is now sacrosanct, and its power is unchallenged, but it wasn’t always, and this is more a political consensus than a fact of nature. The argument for it is more its convenience and efficacy - fiscal stabilization has too many open questions, and the political cycle incentives are too strong, it might seem, for taxes and spending to stabilize spending.

And the degree to which the Federal Reserve, and most developed country central banks, have power over their economies through their credibility is the most interesting part. There’s very very little that rates actually do on the economy - in the US, there’s not a lot of mortgages with flexible rates, there’s very little purchase on credit, and overall the labor market channels seems weak. It just seems that businesses believe the Fed will move around the economy until whatever it says happens, so they get in line, and it happens. “Forward guidance” or “Open Mouth Operations” are just fancy verbiage for “scaring the hoes”.

The Fed’s intervention, alongside the FDIC, can be seen as the opposite - reassuring the hoes. Everyone is scared, and scared people do stupid things, so the Fed wants to cool the temperature - nobody is going to lose their money, relax, just chill out. The non-bailout bailout is key: nobody has to pull their deposits if the policy of the sheriff of dodge is to give everyone their deposit back. The financial system at large would have probably been fine if the Fed just sat on its behind and did nothing, but there were risks attached to that, so instead the Fed went all out (forgive me master) so nobody did anything dumb and no other banks imploded.

The key thing here is trust, or at least confidence, or at the very least belief. The Fed has power because the crucial stakeholders in the economy believe in its ability and commitment to keep the orchestra playing.

The Banshees of Silicon Valley

Silicon Valley Bank had been insolvent, by some measure or another, at least for a month, if not up to three. So why did people stop trusting it suddenly last week? And why might they stop trusting it now? Well, we need to start thinking about why people trust their banks at all.

I’ve written about this before. The bank, when it takes deposits, doesn’t actually have little piles of money with everyone’s names next to them. It has a big spreadsheet that says “Maia has X amount” and when someone gives me money or I spend money, they change the numbers on both parties’s spreadsheets. There isn’t any money changing hands - just changes in ledgers. And trust in your bank is twofold: trust in the ledger being accurate, and trust that the ledger is still going to be usable when you need it. At the same time, banks loan you money by taking a little bit from their own spreadsheet (that has everyone’s money on it) and giving it to you, and they do this because they trust you to pay it back.

Fundamentally the trust you have in your bank is trust in its solvency and its liquidity. You trust your bank to not go out of business, and you trust your bank to have enough cash to let you use it. The transactions system conducted by banks functions precisely because all sorts of laws, regulations, and norms have been put in place to guarantee this as much as possible (balanced, of course, against other interests). The value of a bank comes from the fact your debit card won’t bounce if you try to use it.

Money as a whole is the same. The reason why anyone thinks that money is valuable, when it’s pieces of paper and numbers on a screen, is that they know other people think it too. The whole system is underpinned by pure trust. Prisoners use cigarettes and ramen soups, not because they think it’s valuable, but because the social norm is that you can pay for things with cigarettes and ramen soups. There was even an island which utilized gigantic stones as money, called “Rai”, and they simply agreed on who owned which without them ever changing hands - and even went so far as using stones that had fallen to the bottom of the ocean. Money that is cigarettes, or stones, or even gold has different properties, of course, but the entirety of the value of both the money and the system of money comes from trust in its value. If this trust collapses, money stops being valuable, and people stop using it.

People trust their money is valuable and their bank is solvent for the same reason they trust their friends like them - it’s just what you do. You can collect proof they don’t, but normally things just work out. But of course, friends stop being friends. The Banshees of Inisherin, another movie I loved, tells the story of two close friends, Padraic and Colm, who suddenly stop hanging out because Colm just doesn’t like him anymore. Nobody understands this, but the trust between the two vanishes, and the relationship implodes and turns highly adversarial.

The reason probably comes down to their personalities (Colm is very depressed, Padraic seems very oblivious) but it’s just a random occurrence what changes them from close friends into bitter enemies. Bank runs are kind of the same - people just don’t like their banks no more. This could be rational (as the Nobel Prize 2022 says) or it could be irrational (the previous explanation had to do with manias and panics), but at the end of the day, it’s just a complete breakdown of a previously functional relationship.

Of course, Silicon Valley Bank was insolvent. But nobody seemed to mind, and sometimes troubled banks skirt in and out of insolvency. It just seemed that a lot of tech founders simply didn’t like SVB no more, all pulled out their money, and the bank imploded because of it. I used to think you were solvent. But maybe you didn’t use to be. Oh God. Maybe you never used to be.

Conclusion

If this is the start of a second 2008, it would be history repeating itself as farce - first a financial institution fails because it had completely made up assets (FTX) and now another one fails because nobody realized higher interest rates would destroy their assets and reduce their deposits. But I don’t think it is.

Trust the plan. Patriots in control. Until they’re not.