Taylor Swift (if you haven’t heard of her you need to go outside, even my 85 year old grandma has heard of her) is back on tour after a five year hiatus, and her fans all over the American continent are here for it. Tickets for the Eras Tour, which accompanies her latest album “Midnights” (editorializing now: it’s very good), have been a notorious source of debate - from online outrage to actual congressional hearings.

There’s two major questions here: why are Taylor Swift tickets so hard to come by, and why is it much cheaper to attend performances in Latin America than in the US?

She lets us bejeweled

The core issue with Taylor Swift Eras Tour tickets is that there’s a limited number of them, which is significantly smaller than the number of fans that want them. Basic economics would tell us this means prices would be high. End of story, right?

The main thing to consider here is that Taylor Swift has a monopoly on Taylor Swift. Additionally, her fanbase (the Swifties as they are called) is extremely devoted to her, and regardless there are very few artists similar musically and similarly able to put on such a show - I mean what are you going to see instead, Haim?. This means that Taylor has completely cornered the Taylor Swift market, with few alternative competitors, and a highly captive market. Generally, for a monopolist, consumers that are less sensitive to prices and fewer suppliers are strongly correlated with higher profit margins - meaning that tickets would be even more expensive than for another equally popular artist.

Another layer of monopoly, which is what prompted the US Congress to get involved, is the sale platforms for tickets themselves. Ticketmaster, the platform in question, controls 70% of the market for US live entertainment tickets. According to most economic models, a company with market power will squeeze consumers for all it can, through higher prices, lower quantities, and lower quality. The first one is obvious here, especially since Ticketmaster also has a number of obscure fees that it forces consumers to pay. As per the number of events supplied, it’s plausible, because it can also shake down performers - Ticketmaster has sold around 80% of US tickets since the 1980s. And the last one is the one that bothered the aforementioned Swifties the most: monopolists have as little incentive as possible to actually improve the quality of their business - investment in new technologies, better infrastructure, or simply better products is discouraged because there is no alternative to compete with. This led to a broken, unstable site that crashed under the pressure of the event and led to many consumers unable to purchase tickets.

One of the ways in which monopolists take as much profit as possible from consumers is price discrimination, the subject of one of my favorite posts I’ve written. Price discrimination simply means charging different prices to different people. The key to understanding discrimination is that consumers each have a maximum price in mind to pay for a product - for example, recently I was talking about a pair of jeans I bought with my therapist; she asked me how much it cost, because she’d liked it, but she realized it was too expensive.

One way to do it is perfect discrimination (also called first degree discrimination), where each consumer is charged the exact maximum amount they are willing to pay, up until it’s unprofitable to sell - which, in fact, is not an inefficient kind of monopoly, since everyone who could be served profitably by any firm is served. They simply get no benefit out of it; it all accrues to the monopolist. There aren’t very many examples of perfect price discrimination, but therapists can be said to engage in it, by charging more comfortable patients more. Another type of price discrimination is based on observable characteristics (“third degree” discrimination), such as age, or ones that are easily disclosed; this is done so that consumers who are more sensitive to cost will still participate, at a discounted price. Discounts for locals (more on this here), special tickets for age groups, or ladies’ nights are all examples of third degree discrimination.

The last kind of discrimination, and the most important kind, is second degree price discrimination. In it, different packages of products (normally different quantities) are sold at different prices, which are normally made up of a fixed component and one that reflects the willingness of different types of consumers to pay for it. As mentioned above, the consumers most sensitive to price get better deals, while the most loyal clients get squeezed. A non-Taylor related example is the fact that, in many places, ordering two half portions is more expensive than one full portion: the half-portion fans demand less, so they’re the ones paying more.

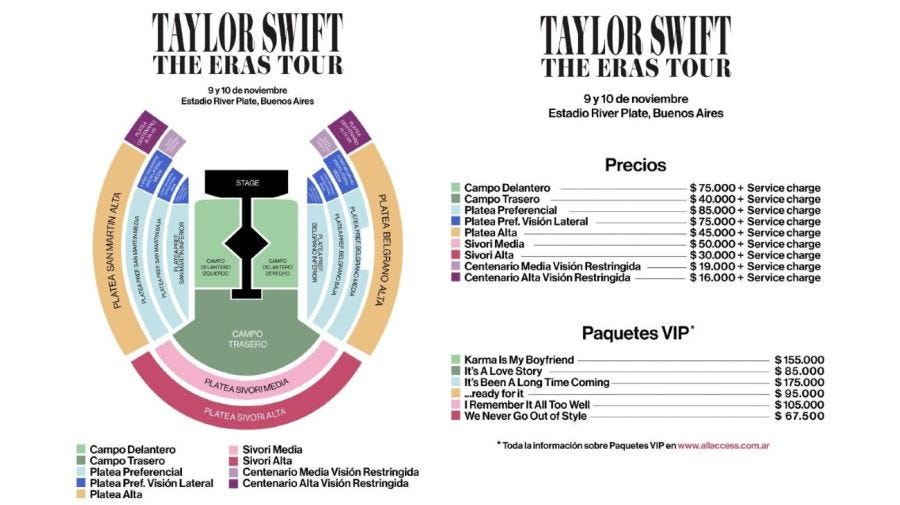

Second degree price discrimination is why normally ticket prices for different locations on concerts (I go to the opera, and it’s the same) are different: they package up different experiences at different price points, tailored at different audiences. The way the Eras Tour seems to be dividing up fans is through a two-part tariff, which is when the fixed price component is a lump sum (for instance, a “service charge”) and the discrimination happens through the rest of the price.

Ms Worldwide

The second question that’s prompted Taylor Swift debate concerns the large differences in price between the US shows and the Latin American shows: while US fans had to shell out thousands to see her perform, their neighbors south of the border paid between 200 and 40 dollars for comparable locations. Why even is that?

A first approximation is quite simply supply and demand: imagine that all things are equal between the US and Latin America (tastes, conditions, venues) except that, because wages are lower, then costs and incomes are lower too. Since costs are lower, “supply” is higher (it would be possible to perform more for the same amount), and demand is lower because of lower incomes. This would mean that the price charged for a similar amount of concerts is lower - despite identical concerts and preferences!

As a general rule, prices for the same things in developed countries are higher than in developing countries. For example, the price of a haircut in New York City is 73 dollars, while it is only 4 dollars in Jakarta (Indonesia). Big Mac prices are different in various places, and are used as gauges for the value of a currency - something Argentina exploited to look better in international statistics. This discrepancy is known as the Penn Effect (the main explanation is known as the Balassa-Samuleson Effect), and it is largely explained by trade: richer countries tend to be more productive (i.e. better at turning work hours into things), which means they trade with other countries at better prices; this results in incomes getting pushed up in the most productive sectors, which boosts earnings in other sectors too - if the tech industry has more money, everyone else will start charging more. It’s the same reason why big cities are also more expensive than smaller cities. Additionally, richer people spend more on services, which results in service prices being higher overall the richer societies are. The relationship between incomes and service prices is generally complicated, but as a rule of thumb, poorer countries tend to be cheaper.

But why do more productive economies have higher wages in sectors that are equally productive? Teachers in the US make more than teachers in Nigeria, even though schools can’t be that different. The main reason is simple: if engineers make more money, then other people who closely compete with engineers also have to pay more, to keep up with them. And the substitutes of the substitute have to pay more. And so on and so forth, with decreasing strenght. This results in the wages of people who are nowhere near the top of the productivity scale to grow alongside the most productive employees in the most productive sectors, simply because the companies and organizations employing them would be deserted. A classic example is musicians: violinists make much more than in the 18th century, even though they play the same music in the same instruments. If an orchestra tried to pay the people performing The Magic Flute as much as they did when Mozart premiered it, they would all get jobs at McDonald’s instead - so wages have to go up somewhat if a society gets richer.

Does this mean that Latin America can expect a large sudden inflow of American Swifties for the Eras Tour? Unlikely. The main fact here is that airplane tickets and lodging are not cheap - so it might not make actual economic sense to pay nearly a thousand dollars in airfare, plus a good hundred or two on a hotel, just for a ticket that costs as much as the travel expenses back home.

The second explanation is more complicated, and is similar to why rich country firms don’t invest that much in poor countries: if poor countries have fewer companies, then investments would be more profitable because there’s fewer competitors. But international investment is almost all between rich countries. So why is this so? A first explanation is that first worlders don’t have a lot of information about business opportunities in the third world, especially surrounding the practical aspects - if veteran tech entrepreneurs could fall for Theranos or FTX, what’s to say they’ll know what’s a good pitch and what’s a scam in Nigeria, rather than their own metier. Secondly, the important part is having a very little capital to output (i.e. having very few factories and businesses for the size of the economy), and not to have very little capital period - so countries that spend a lot of what they earn are good investments, not countries that have very little money to spend; the former have plenty of opportunities for new companies that locals aren’t starting, regardless of income, while the latter might simply not have anything to spend or invest in.

Secondly, poorer countries have worse institutions: governments are corrupt, crime is up, and they’re poorly managed; they also have worse economies overall, meaning that there could be a massive recession out of nowhere that wipes out your investment. Another important fact is that poorer countries have fewer educated people, which results in less qualified staff - and also poses an analogue puzzle for immigration: why are almost all immigration flows to the first world, rather than the other way around, since educated people could get a much bigger bang for their buck in India than in California? Well, there’s fewer information about opportunities, a worse standard of living (think crime), and such unimportant nonsense as “I don’t have any friends or family there”. This also means that travel from the first to the third world has major obstacles that do play, on a smaller scale, in the Taylor Swift Eras Tour - immigration is mostly about economics, and Swifties are about Taylor, even when the obstacles are the same.

Conclusion

So, all in all, there is no economic puzzle, either in why tickets are so expensive, or why they’re less expensive outside the US than within. The true puzzle is why people ask for Olivia Rodrigo to be the opening act for Taylor’s LatAm shows (instead of Sabrina Carpenter), given that she’s Filipina and not Hispanic.

The only remaining factor to address is the outrage: why are tickets allocated to those who pay most, rather than true fans? This is a question for ethics, not economics, but it’s also a question for economics - ethical objections shape markets just as much as economic forces. Before Adam Smith, what passed for economic theory would have four components: production (“supply”), utility (“demand”), exchange (“markets”), and final distribution. The latter is a bit muddled, but it mostly concerns who gets what and why. The outrage Taylor fans have over prices and income as the mechanism that allocates tickets isn’t about exchange, but about distribution: they think it’s unfair. And it might as well be. But “how do we design a system that is more fair” is not really a question I can answer with economics, even though, to quote Ice Spice in the Karma video, “facts”. We need Al Roth’s blog to tackle the Tayonomics of mechanism design.

The only thing that's a bit mysterious is why prices aren't even higher. Given that they are selling out, it seems she should raise prices.

I thought this was going to be about relationship drama, but instead I have to learn about economics? I didn't sign up for this