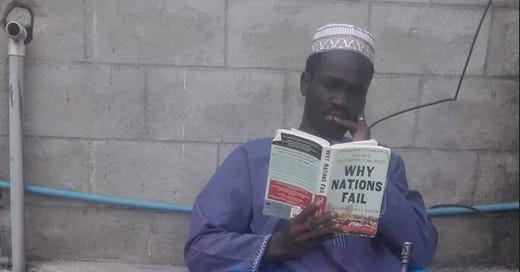

“Why Nations Fail” by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson is one of the best-selling economic history books in recent years; it’s one of the most well-known too, and has raised the intellectual stature of its author by quite a bit. To its credit, the book is convincing and well written, and its central premise, that institutions are the fundamental cause of long-run growth, is right on the money. The book’s interesting thesis and solid prose actually got me interested in economics as a field of study when I first read it back in 2015. However, one of my most controversial opinions is that it’s not very good in its content or in the argument it puts forth.

The politics of poverty and prosperity

The main thesis is pretty simple: there’s two kinds of institutions, inclusive and extractive. Inclusive institutions are sets of rules and norms that allow for stable and well-executed rulemaking by the state, a competent provision of public services, participation in an open market, and protection of property rights. Meanwhile, extractive institutions are set up so that a small cadre of elites can comandeer the state for their own purposes and line their pockets through corruption, rent seeking, or plain and simple theft and exploitation.

A good example is North and South Korea: the two, being a single nation for centuries, suddenly split between two incredibly different economic and political systems in the 1950s; and decades later, South Korea is a rich democracy and generally considered a developed nation, while its communist counterpart is a repressive autocracy with incredibly low standards of living. Since initial conditions weren’t that different (in fact, North Korea was the richer of the two during and after partition for a while), then most explanations that don’t rely on institutions can be ruled out - its unlikely the two had radically different geographies, cultures, natural resources, or knowledge of economic doctrine right before and after the Korean War.

Of course, the big issue is that exactly what are inclusive and extractive institutions is left vague throughout the book, generally serving the purpose - if a country develops long-term, then its institutions had to be inclusive. But South Korea (and the other “Asian Tigers”) were, until the 1990s, incredibly repressive dictatorships plagued by corruption and malfeasance - meaning that if their development agendas hadn’t succeeded, we would consider their institutions retroactively extractive; likewise, the similar governments of Latin America, which pursued similar policies and had similar issues with institutional quality, would probably be considered models of inclusivity if their development strategies (which were, in fact, pretty similar to East Asia’s) had worked out instead of being abject failures.

A clear example of the thin and the contextual nature of inclusive vs extractive institutions can be found in the two main forms of exploitation of the native Peruvian population by the Spanish: mita and encomienda. Mita consisted of mandatory but paid labor of a limited duration (derived from a similar Inca tradition, in fact), and encomienda was perpetual indentured servitude. In Peru, mita was directly run by the Crown and its representatives and was most frequently used in mining districts, so that the natives would extract and refine gold and particularly silver, while encomienda was deployed by local aristocrats in agricultural areas. Now: which is more extractive? A paper like Engerman & Sokoloff (2000) would argue that plantation-style agriculture of the type the encomendados profited from would generate a class of politically repressive elites that would hold back growth, even when mining labor was incredibly hazardous. However, Dell (2008) found the opposite: mita districts, to this day, are much less economically developed than encomienda districts, because the much dreaded encomendados acted as a local pressure group on Peru’s overall extractive government to secure local infrastructure.

The reason why institutions, and not something like technology, makes or breaks a nation’s success is pretty simple: to try to innovate, you have to both take a risk yourself and expose established players to the risks of your success. Under inclusive institutions, when anyone innovates, everyone benefits, and the losers have to adapt or bow out. Meanwhile, under extractive institutions, the losers can simply band together and demand the government put a stop to the innovations - if they even happen at all: under insecure property rights, it’s anyone’s guess as to whether you’ll even get to start a business without greasing the palms of every municipal official under the sun, let alone be able to prevent your ideas being stolen, or your income taken by local protection rackets.

I’d say that the book’s weakest aspect is that, even when institutions are the ultimate cause of growth and development, the proximate causes are ignored. Technology (as mentioned above) is one of the biggest proximate causes, and the institutional framework required to created and/or adopt technologies that threaten enshrined interests is pretty clear. But looking at something like political systems, i.e. democracy versus autocracy, the relationship becomes incredibly complex - does democracy cause growth, does growth preserve democracy, or is there some third factor common to both prosperous and pluralistic polities? (see here for more on this). And aspects such as culture are ruled out, even tho there’s some evidence that cultural differences account for different incentive structures between US regions to this day.

The conceptual basis for the book is solid (good institutions develop nations, bad ones don’t - groundbreaking, get them to Stockholm) and the anecdotes used to illustrate them are, well, illustrative and clear. But in economics, the way to actually stake out a claim is to rigorously prove it either empirically or theoretically. Generally, the book is based on Acemoglu and Robinson’s previous work on development and institutions (plus a third economist, Simon Johnson) - so it’s only fair to turn our eyes towards the duo/trio’s oeuvre to figure out if their claims actually make sense or not.

In particular, we’ll be focusing on three papers: “The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth” (2005) by Acemoglu, Johnson, & Robinson (henceforth AJR); “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution” (2002) by AJR, and the heavy hitter that first established the trio, and Acemoglu in particular, as major figures in development econ: “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development” (2001).

Colonies and Colonizers

The Rise of Europe (AJR 2005)

Most of the analysis of the impact on colonialism focuses (rightly) on colonized nations, but there is a lot to be said about how it impacted colonizers as well. The claim AJR make in this paper is fairly simple and straightforward: the countries in Western Europe that had more inclusive political institutions before colonizing other nations developed stronger property rights due to the greater influence of merchants on the political process. Thus, trade and colonialism in the Atlantic was beneficial to colonizers (a group made up of Britain, France, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain), and who kept those gains was either a small elite cadre or a larger group of merchants and seafarers, depending on how “tyrannical” the government was.

The importance of the Atlantic trade and of colonialism cannot be overstated: Western Europe was not significantly richer than Eastern Europe or Asia before the 17th century, but began steadily diverging ever since - but only for nations involved in trade, as the rest of Western Europe (think Italy or Belgium) did not benefit. Citing North & Weingast (1989), AJR posit that political, not economic, institutions were the key to growth: the less tyrannical a nation during the Age of Discovery, the likelier it was to later develop a capitalist regime with strong property rights, since merchants could simply petition their relatively weaker sovereigns.

The issue isn’t the relatively straightforward thesis, but rather the much weaker empirics: GDP per capita isn’t reliably available, so urbanization is assumed to be a good proxy for it (using data from the next paper to trash). The regression is pretty simple: urbanization as a product of geography, time, some fixed characteristics of countries, and the potential for Atlantic trade through various measures - particularly comparing Spain, England, and non-traders.

The main issue here concerns the identification strategy, which is comparing Western countries that traded to those that didn’t. If the differences in trade status or trade volume were caused by factors unrelated to institutions, then the two are a valid counterfactual to each other (for instance, think geography); however, if there are systematic institutional differences between traders and non-traders then you don’t have a valid counterfactual, and therefore aren’t comparing apples to apples. Thus, instead of random assignment, what you end up measuring is that countries that are favored to trade more, do actually trade more - astonishing!.

A second issue here is simply that the sample is very small: there’s only a handful of countries considered, and a handful of time periods. Thirdly, the quality of urbanization data isn’t very good (more on this later), the division between traders and non traders is a bit arbitrary, and the way institutions are accounted for is also arbitrary and weird (“Protestant” and “Roman”). Lastly, the history is a bit shaky: Spain and Portugal acquired most of their colonial possessions in the 1500s, while England and the Netherlands did so a century later - more than a century passed between the Fall of Tenochtitlan and the Purchase of Manhattan.

Reversal of Fortune (AJR 2002)

“Reversal of Fortune” is a paper with a pretty simple claim: countries that had higher population density, and/or bigger urban populations, in 1500 (before European colonization) now have lower GDP per capita. Population density and urbanization are (generally) considered positive signs of development, so what gives?

The proposed relationship is pretty simple: countries that had higher urban populations (and were therefore richer) also had either more resources and/or more organized governments - compare the Inca Empire with the relatively less organized and less wealthy tribes just a few hours south, in Northwestern Argentina and Chile. This meant that there were more resources to exploit, more people to exploit them with, and a generally overall more streamlined manner for exploitation. In consequence, European colonizers imposed much worse institutions on the originally richer countries, since they could get more out of them, and the rest of the empires was left to do whatever - eventually developing stronger property rights and whatnot. A good comparison would be Mexico, which had the wealthy and well organized Aztec Empire, to the United States or Canada which, while they did have interesting and rich cultures, they did not have the same degree of urbanization and political development as the Aztecs (or the Maya or even the Olmecs), at least not consistently and throughout the same time period. Resultingly, the Spanish enslaved most of Mexico’s native population to extract mineral wealth and participate in plantation agriculture, while British settlers mostly focused on “producing” (while also brutalizing the natives in countless other manners, and later engaging in similarly gruesome acts).

The identification strategy seems to be decent, and the links between original population density (or urban population) and current wealth, via more extractive institutions, seem to be reasonable and reasonably well elaborated - even though history is often complex, and why Australia was not colonized by the Dutch1 in the same manner as Indonesia can’t really be explained fully by “more people”.

Colonial origins and original misgivings

The most famous paper in the bunch is “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation” (2001), which is pretty much the paper that made Acemoglu’s career as a researcher and why he’s usually touted as a future Nobel laureate.

The paper has a simple strategy to prove institutions, not geography, cause development: because better institutions and better GDP are also correlated to variables that aren’t measurable, you need a middleman between the two. This “middleman”, called an instrument, is correlated only to the cause variable (institutions) and not to either the consequence directly (GDP) or to other unobservables that might be mucking up the correlation (culture, for instance). The instrument is then used as a proxy for the cause variable. The main thing about the instrument is that it has to be very tightly correlated to the variable it’s a proxy for, and that it cannot be correlated to any other variable under consideration.

The instrument Acemoglu et al. use is settler mortality: different places had different geographic conditions, which Acemoglu assures as are exogenous (i.e. uncorrelated to anything else), and those conditions made it so that settling in some places was pleasant, and unpleasant in others. Unpleasant locations needed more slaves and were more overall extractive, so they had worse development over time; meanwhile, pleasant locations ended up with more Europeans doing the hard work, and had better institutions. The regressions show, unsurprisingly, that this relationship holds.

First issue is, as usual, the data. The paper’s most important chart, showing the relationship outlined above, has a pretty interesting kink. See if you can spot it:

That’s right: there’s huge columns of countries with basically identical settler mortality figures. And this is kinda sus, so an expert looked at it and concluded the data is pretty bad and that, using better data, the relationship only holds for the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Secondly, there appears to be a massive problem with the instrument: the estimate for the institutions - GDP correlation is smaller than the one for the mortality - GDP one; this means that, rather than taking out the problematic unobservables, the instrument is adding more of them. This is because using geography as an instrument is super flimsy2: things like disease, rainfall, and terrain are linked to other variables and those variables to GDP. Because geography was also an issue for what economic activities each country performed, you'd get a massive confounding factor: slavery.

Thirdly, the history being used here is a mess. In Acemoglu’s world, Colombus did the Scramble for Africa, and Pizarro also dabbled in Indonesia and India. But the real world wasn’t like that: Latin America was conquered much earlier, and very slowly: Buenos Aires, one of the largest cities in the Americas, was a backwater smuggling port until 1776. That as much time elapsed between the conquests of Mexico and Africa as between the Age of “Discovery” and the Norman Conquest means that exogeneity of the instrument is out of the question if there is even a faintest hint that countries weren’t conquered randomly, which they weren’t. Plus, which countries colonized whom and when isn’t random either: Spain, a country with terrible institutions, got a head start, while England got there much later and the Netherlands simply did atrocities to the Indonesians - and this was a big deal!. And additionally, that Latin America was conquered early had consequences for Africa, which supplied the slaves that grew sugar and cotton: African economic outcomes are much worse today in countries where the slave trade prospered.

One last thing is that, if Reversal of Fortune is true, then Colonial Origins can’t be: countries that were richer pre-Europeans are poorer now, and vice versa. But why were those countries richer? Well, both papers say institutions + geography, but geography also had to be shaped by institutions - Tenochtitlan was, after all, built on a swamp. But if you, as this paper does, control for the quality of pre-colonial institutions, then the entirety of the correlation between geography and post-colonial institutions disappears: it seems some places just had it bad and the Europeans just made it even worse.

Conclusion

So, in conclusion, Why Nations Fail is an imperfect book with an imperfect thesis based on deeply imperfect research. Which is a shame, because I agree with the core thesis and because it’s a very interesting book - it got me into economics, after all. Acemoglu was (apocryphally, by someone on my Twitter private messages) described as “Wikipedia with charts”, but Wikipedia can be pretty fun after all.

I also don’t like Acemoglu’s later research, which is just political Wikipedia with charts, but leave that to poli sci bloggers because it’s not my bone to pick.

Sources

Note: “Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson” is abbreviated as “AJR”

Previous posts on the economic legacy of colonialism and the economics of democracy are interesting and somewhat related

General

AJR (2012), “Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth”

Peter Dizikes, “All the difference in the world”, MIT News, 2012

Colonizers and colonies

AJR (2005), “The Rise of Europe: Atlantic Trade, Institutional Change, and Economic Growth”

Bandyopadhyay & Green (2010), “The Reversal of Fortune Thesis Reconsidered”

Colonial origins and original misgivings

AJR (2001), “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation”

McArthur & Sachs (2001), “Institutions and Geography: Comment on AJR (2000)”

Olsson (2004), “Unbundling Ex-Colonies: A Comment on AJR 2001”

Fun fact: the Dutch were the original colonizers of Australia, which was called “New Holland”. That’s where “New Zealand” came from - Old Zealand is in the Netherlands! Less fun fact: the people who carried out that one, the VOC, were not nice.

First ever recorded instance on this blog of Jeffrey Sachs making a good point.

For anyone interested, here is AJR's reply to Albouy's critique: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w16966/w16966.pdf

Interesting post. My critique of WNF is that a better version was written about 239 years earlier by Adam Smith. Of course, people who haven’t actually read Wealth of Nations think Smith just says free markets are why nations are rich. But I read Smith as pointing to institutions, not just trade and specialization (which are certainly part of the equation, but not the whole deal).