What Acemoglu has done for institutions, Kim Kardashian has achieved for butts

Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson, and Simon Johnson just won the Nobel Prize in Economics. It is not especially surprising that Acemoglu won, since he has been on the shortlist for the Prize since basically his early career - leading to a long spate of jokes about it (including the title of this post!). Johnson and Robinson, as coauthors of his most important work (and his books!) were a no-brainer to share it (except for me).

The Prize has focused on Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s joint work on institutions and economic development so it will also be the focus of this post, even if all three (particularly Acemoglu) have a lot of other notable work. The subject is one I’ve already written about a few times- including, most famously (it’s my most popular post so far!), about Acemoglu and Robinson’s best-selling book: Why Nations Fail.

Why Nations Don’t Fail

“Why are some countries rich and other countries poor?” is probably the defining question in development economics, more or less, and historically the answer has been… less than clear. There’s some perennial culprits: geography (climate, mainly), natural resources, colonialism, various wars, but economists haven’t really been capable of adjudicating the answer. Why? Well, firstly, because there was no clear boundary between regular macroeconomics, growth economics, and development economics for a long time, but also because the discipline was fairly immature and thus didn’t have an agreed upon method of answering said questions.

But to sum it up: for a really long time, the general belief was that countries were poor because they didn’t have enough investment in their economies, especially in certain sectors that gave traction to economic growth (mainly heavy industry). Thus, the government had to spend a lot of money to get investment to the growth-spurting tipping point, and set up a lot of trade restrictions, regulations, and financial incentives to promote investment into the “good” sectors. The problem is that this approach didn’t work outside of a few countries, and in most cases seemed to be overtaken by corrupt practices of various kinds, so economists shifted gear and said that actually the solution was to embrace free markets, clear rules of economic play, and strong and stable property rights. The success of this new paradigm was also dubious and highly contested, but overall, it also wasn’t clear that countries were succeeding by embracing free, open markets alone.

The “free market” conventional wisdom cycle also produced very few newly developed countries, so everyone was left with the impression that governments weren’t adopting good policy recommendations and were instead just doing whatever. So the question became why weren’t governments adopting good policies, and most economists seemed to think that it was because the countries in question didn’t have the correct institutions to produce governments capable of making good policies.

Institutionalized

Let’s start with the obvious: what are institutions? Well “institutions” is a bit of a nebulous term in economics (good thread about them here), but generally it tends to refer to the legal and informal arrangements that shape economic life - the system of government, the system of property rights, customs around both, and attitudes about how “things are done” in the population. So, overall, institutions can be said to be “how the government works” and “how the government makes the economy work”.

One example comes from British farming policies in India: according to Banerjee & Iyer (2002), the British set up distinct schemes for who profited from farming: in some, the farmers did, and in others landlords collected the revenue for the farmers. After controlling fora really wide array of geographical and technical conditions at the start (because improvements to the land and tools by the farmers are obviously a variable of interest), they found that the farmers who profited from the land directly invested more in their farms, with crop yields being 23% higher, overall higher prosperity in the area, and better quality of life (child mortality 40% lower). So it’s not just the system of government, it’s also economic systems and policies.

A very influential early paper on institutions was North and Weingast (1989), which linked the Industrial Revolution to the Glorious Revolution: basically, the civil war between royalists and parliamentarians resulted in a less powerful monarchy that was forced to respect certain boundaries on its power, which in turn increased certainty among property owners and let them invest, which over time (100+ years) resulted in the Industrial Revolution. This is quite a long-ranging subject (“why did the Industrial Revolution happen” is such a complicated topic I’ve held off on addressing it for 2+ years), but there are some major critiques of the North thesis, though overall “good government allows for more economic growth” tends to be a semi-settled question.

So, why do some countries have bad institutions? Well, it’s not hard to notice that if you look at the richest countries in the world, they tend to be countries that had colonies, while the poor countries were the colonies. So maybe it was the colonial powers that set up bad institutions - but since not all "poor” countries are equally poor, it stands to reason that there has to be something else in play, because Uruguay, Colombia, and Haiti were all colonies but still have different degrees of (under)development.

Let’s take an example roughly contemporaneous to the Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson papers: Engerman & Sokoloff (2002). They argue (using much less substantive methods) that the link between colonialism and institutions was mediated by slavery and coerced labor - in particular, that the natural conditions (tropical climate and/or mining resources) incentivized systems of coerced labor in plantations and mines (which relied on slavery and the mita and encomienda systems of indentured labor). These large-scale, labor intensive activities led to significant wealth inequality within societies, resulting in an economically dominant elite holding all of the power over post-colonial institutions. This is not unambiguously true: the gold mines of Colombia showed this pattern, but the Peruvian silver mines showed the opposite, and there’s no evidence that the channel was slavery itself, so the effect seems to be rather the consequences of concentrated wealth and property ownership, as well as political and economic disenfranchisement.

Why “Why Nations Fail” Succeeds

Work colonies are possible for European nations only in temperate climates; in hot zones the European cannot perform the heavy work demanded by the cultivation of a colony. They are only possible in very thinly populated regions, in which a very primitive mode of production predominates…

Exploitation colonies work quite differently from work colonies. They lie in the tropics where the European cannot perform hard work. There, the working classes can only be composed of natives or of imported inhabitants of other tropical or sub-tropical countries, (…) The European does not seek a home in the tropical colony but rapid enrichment. The quickest way to this, however, is by plunder, and the richer and more numerous the people are who are to be plundered, the greater the riches yielded.

Karl Kautsky, “Socialism and Colonial Policy” (1907), chapter IV and V

The discipline, then, saw a confluence of three factors: first, an interest in institutions as a cause for economic development; secondly, a more developed understanding of institutions themselves (from New Institutional Economics, for which Douglass North won the Nobel Prize in 1993), and thirdly, advances in quantitative methods and increased rigor in quantitative questions (Engerman & Sokoloff, despite coming out after AJR 2001, is a much more methodologically old-fashioned paper).

So what do Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson (henceforth AJR) think about institutions? Their most famous paper as a group is “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation” (2001). The issue in question is that, while better institutions and better GDP are also correlated to each other and to variables that aren’t measurable, you need a middleman between the two. This middleman is called an instrument, and it’s only correlated to the cause variable (institutions) but not to any of the consequences (GDP) or other unobservables. You can test the first step of the relationship, which is somewhat strong in AJR 2001, and the other two are more or less just leaps of faith.

The instrument AJR use is the mortality rate of European settlers, which are caused by various geographical conditions (mainly, climate) and which are variable across developing countries and not systematically correlated to economic outcomes. The higher settler mortality rates would have thus incentivized the adoption of practices like slavery and forced labor, which in turn resulted in a less representative and more coercive system of government - that is, extractive institutions. Meanwhile, countries with better conditions of life created institutions similar to the ones in Europe, which over time resulted in a more representative government with more respect for private property - or inclusive institutions. The regressions used by the paper, between settler mortality rates in the XIXth century and present GDP show, unsurprisingly, that this relationship holds.

The paper has a number of criticisms made later on. First, there are major concerns with the data, which interpolates unavailable mortality rates with either posterior ones or those from other countries; using better data, the relationship only holds for the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Secondly, there appears to be a problem with the instrument: the estimate for the institutions - GDP correlation is smaller than the one for the mortality - GDP one; this means that, rather than taking out the problematic unobservables, the instrument is adding more of them. This is because geographical variables make for bad instruments, particularly since disease, rainfall, and terrain are both tied to the mortality of European settlers and to other variables and to GDP, directly and indirectly. For example, settler mortality could also measure human capital, which is not related to institutions very straightforwardly. And, as mentioned above, economic organization also has massive confounding variables with natural resources (tropical climates are good for growing tropical crops), and thus with slavery, per Engelman and Sokoloff.

Additionally, the history in question is somewhat important, particularly since the colonization of the “New World” took place over the better part 400 years: Africa was colonized substantially later and by different countries with different institutions to the Americas. Because of this, medical technology was different as a function of higher overall technological advancement, and more importantly, settler countries had better institutions in the 1850s than in the 1500s (the Glorious Revolution happened in 1688! Good institutions just didn’t exist in 1492): simply put, the time between the Age of Discovery and the Scramble for Africa was around as long as between the First Crusade and the Age of Discovery. Plus, Africa in particular was significantly affected by slavery in the Americas, meaning that data points for institutional quality are correlated to each other and to an unobservable.

A companion paper by AJR, released in 2002, is “Reversal of Fortune” (AJR 2002). In this paper, the question of interest is whether countries that had higher population density, and/or bigger urban populations, in 1500 (before European colonization) now have lower GDP per capita. Why would this be the case, if richer countries are now more urban and more densely populated?

This paper also uses instrumental variables, this time using pre-colonial population density as an instrument for resource abundance, and is overall fairly similar in its procedings. The relationship is pretty simple: countries with higher urban populations also had either more resources and/or more organized governments1. This meant that there were more resources to extract and more people to indenture into extracting them. In consequence, European colonizers imposed much more extractive institutions on the originally richer regions, while less settled areas were left to their own devices, over time developing more inclusive institutions. For example, the the wealthy and well organized Aztec Empire has a suitable climate for plantations and had mineral wealth; thus, the Spanish enslaved most of the Aztecs’ subjects a lot more easily.

So, if the paper has so many problems, why did it prove so influential? First, because it utilized cutting-edge techniques at the time (instrumental variables was a new thing back in the 2000s), and because it used novel datasets and clever inference to answer a big-picture question. While “the conditions of colonization determined the institutional quality of colonies” is not a new idea (in fact, Marxist Karl Kautsky came up with a similar idea in 1907), treating it in a formal and empiric manner like this was fairly novel in the 2000s.

AJR World

The authors have a series of collaborations with each other that further and deepen this understanding of institutions.

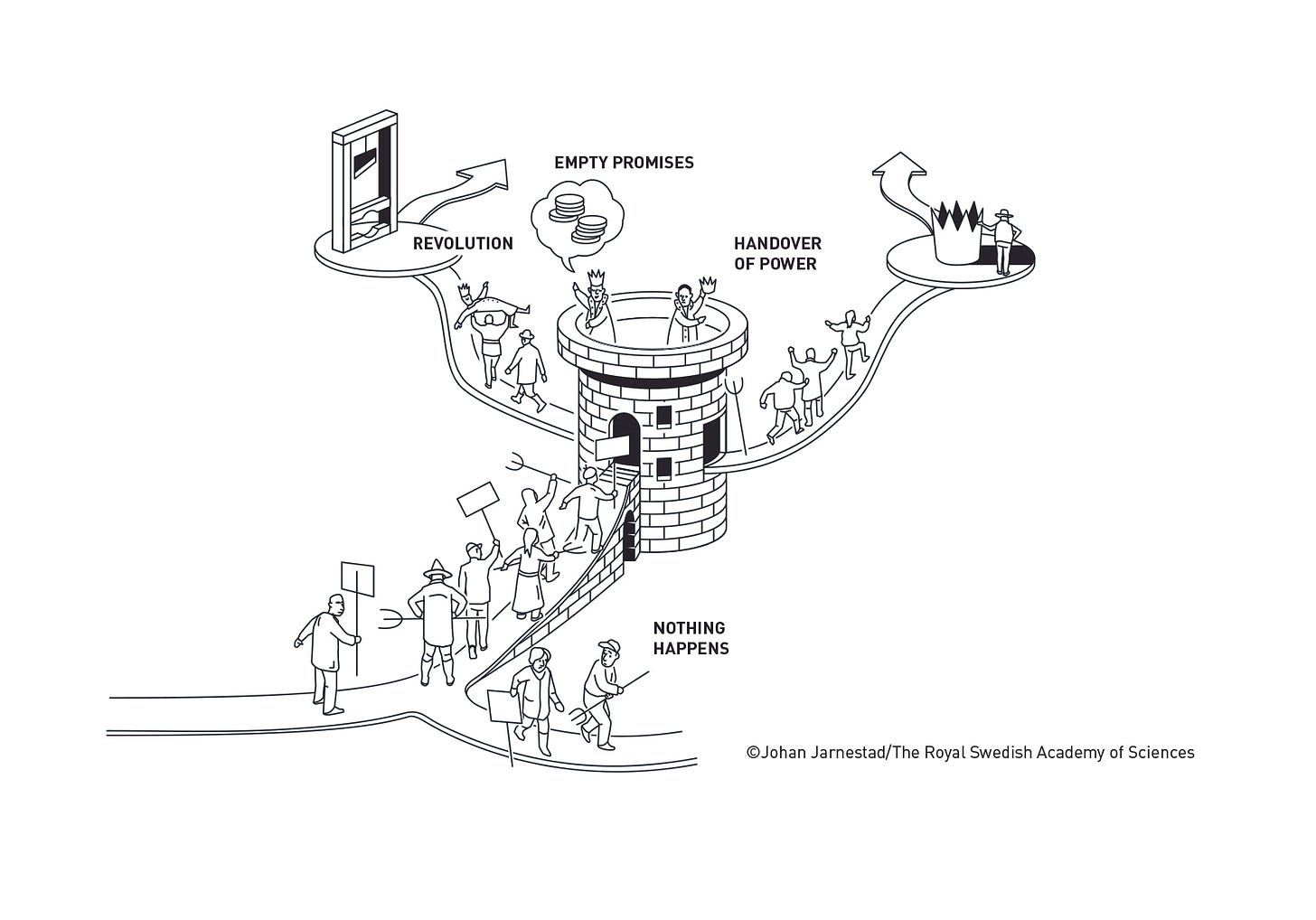

Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s joint work proposes a basic framework: countries have political and economic elites, as well as “lower classes” (middle class professionals, urban workers, and the poor) who have both less wealth than the elite and less political power. In non-democratic societies, the lower classes may want to contest the power of the elite, and they can only do this via violent revolts. To avoid them, the elite might democratize society: they may only do this if the elite cannot credibly redistribute wealth to the lower classes. If unable to redistribute (because of administrative or economic issues), then it has to redistribute political power, because promises of redistribution in the future aren’t credible without a political channel to force them and thus cannot stave off revolution. Contrarily, if initial inequality of wealth is very high, the elite may also stage a coup d’etat to prevent their wealth from being seized by the democratic governments. This can also happen even if the government is capable of transferring wealth, because there are many impefections in real-world economies that cause wealth redistribution to falter: problems with extracting revenue, problems with wages or “commodity” prices, and manipulation of tax rates to supress other classes.

The picture this paints is quite somber but simple: if the main concern of the political elite is to prolong its grasp on power, it will take action to reduce competing sources of political and economic power. This creates a dichotomy: if changes in the economy reduce the economic power of people without political power, or reduces the economic power of people without reducing their political power (think: in a democracy), then they have no way to block the changes to the economy. However, people who would lose their political power from economic changes (for example, slaveowners), have every incentive to block them, and often do, harming the overall economy. This means that political elites only block new technologies when they are not entrenched enough that a new “tech class” would threaten them, but not when there’s enough political competition that choosing obviously bad policies would hurt their standing with the selectorate.

These studies, put together, mean that economic and political institutions act together to preserve the wealth and power of those at the top (in underdeveloped countries, landowners), who have a lot to lose if either of those change. However, initial conditions may mean that the landowners don’t have enough power to block either change - or that they may have enough wealth to block changes to their actual, real-world power, resulting in extremely unfair democratic practices. This means that, without substantially equal access to political power, society may choose suboptimal economic arrangements because the wealthy have higher de facto power.

Conclusion

So, while there is room to disagree with the methods and conclusions of their research on development, the truth is that Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson built the very room the disagreements are happening in. The picture they paint, overall, is one where democratic participation and shared political power are of the paramount importance for economic performance over the long term - and that, if captured, it is extremely difficult for non-democratic institutions to become democratic. In a context where democracy over the world is under stress, particularly with the looming election in the United States, this becomes the most important factor to take into account.

For further reading by me on this general line of research, you can read previous posts about development aid, colonialism, and my review of Why Nations Fail.

You can also read the summary the Prize itself put out of the laureate’s research (for the general public and for more technical audiences), as well as a summary by Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson themselves. And here on Substack, you can readan excellent blog post by Brian Albrecht about the Nobel Prize, and Alice Evans’s terrific write-up of Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson’s general interest writing, as well as other subjects that she’s written about herself.

And also, write-ups on the 2023 Nobel Prize in Economics awarded to Claudia Goldin, the 2022 Nobel Prize in Economics (given to Ben Bernanke and two others), and related to the 2021 Nobel Prize for causal inference techniques.

Of course, this contradicts AJR 2001, because it means that geography directly influenced colonial institutions, which means that settler mortality is not a valid instrument, because pre-colonial institutions have a big impact on present outcomes as well.